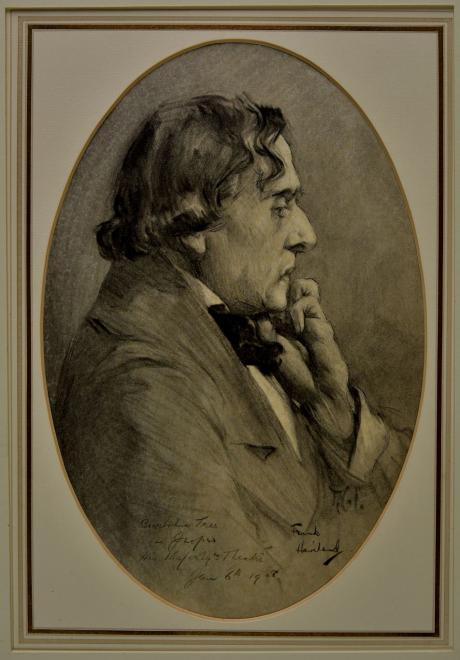

"Beerbohnm Tree as John Jasper/ His Majesty's Theatre/ Jan 6th 1908" and further signed " Frank Haviland"

The Late Robert Hardy CBE, FSA, 1925 – 2017, Actor

Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, [real name Herbert Draper Beerbohm] (1852–1917), actor and theatre manager, was born on 17 December 1852 at 2 Pembridge Villas, Kensington, London, the second of the four children of Julius Ewald Beerbohm (1810–1892) and his wife, Constantia Draper. His father, a London corn merchant, was German-Lithuanian and his mother was British. Sir Henry Maximilian (Max) Beerbohm was his youngest half-brother, from his father's second marriage.

Beerbohm received his education at various schools in England, including Mrs Adams's Preparatory School at Frant, Dr Stone's school in King's Square, Bristol, and Westbourne collegiate school in Westbourne Grove, London; he then attended the school where his father had been educated, Schnepfeuthal College in Thuringia, Germany. At the age of eighteen he joined his father's business, but he spent his free hours performing with amateur theatrical groups, and after eight years he left his clerical job to pursue a vocation as an actor.

During the late 1870s he assumed the name Herbert Beerbohm Tree, and performed with amateur groups. After a successful appearance as Grimaldi in Boucicault's The Life of an Actress at the Globe Theatre (1878), he began his professional acting career when he joined the Bijou Comedy Company for a brief provincial tour. In the autumn of 1878 he secured his first London engagement, at the Royal Olympic Theatre under the management of Henry Neville. Except for an occasional metropolitan stint, by 1880 his experience had been limited mainly to provincial productions of foreign melodramas and farces in which he played German barons, French marquesses, and other eccentric members of the foreign gentry. One such provincial performance, the old Marquis de Ponstable in Madame Favart, garnered Tree an invitation from Genevieve Ward to enact Prince Maleotti in a revival of Forget-me-Not at the Prince of Wales's Theatre during April and May 1880. For the next four years he continued touring the provinces and had a few unremarkable performances in London theatres. On 16 September 1882 he married an actress, Maud Holt (1863–1937), with whom he had three daughters. Treeenjoyed his first major success on the London stage in March 1884, when Edgar Bruce, the manager of the Prince of Wales's, commissioned him to play the Revd Robert Spalding in Charles Hawtrey's adaptation of The Private Secretary. Immediately afterwards, Tree took the part of Paolo Marcari in Hugh Conway's Called back, and the contrast between the timid parson and the dashing Italian spy helped to establish his reputation as a versatile character actor. His career then ebbed, and from late 1884 to 1886 his London appearances in such plays as Pinero's The Magistrate and W. S. Gilbert's Engaged were commonplace and lacked the distinction of his earlier successes. In the autumn of 1886 Tree joined Frank Benson's company for a week at Bournemouth, where he played Sir Peter Teazle and Iago. After this provincial run he returned to London and the Haymarket Theatre, and his career rallied when he turned his minor role of Baron Harzfeld in Charles Young's Jim the Penman into a main feature of the production.

By the spring of 1887, aged thirty-four and with nine years of both amateur and professional experience, Tree had secured a sufficient reputation to embolden him to venture into theatre management, and in April he took over the Comedy Theatre in Panton Street. He inaugurated his managerial career with a successful run of W. Outram Tristram's Russian revolutionary play The Red Lamp, in which he played Demetrius. In the autumn of 1887 he became the lessee and manager of the more prestigious Haymarket Theatre, where he not only raised the theatre's distinction as a major London playhouse (a status it had lost with the departure of the Bancrofts in 1885) but also secured for himself a reputation as one of London's leading actor–managers. During his ten-year management of the Haymarket, Tree produced and acted in approximately thirty plays, mainly melodramas and farces which were standard nineteenth-century fare, such as Trilby and Captain Swift. Trilby, indeed, was the popular sensation of 1895, running to 260 performances. Tree, unlike many West End theatre managers, who eschewed contemporary and potentially controversial social plays, recognized the importance of the new drama, staging Maeterlinck's The Intruder(1890), Wilde's A Woman of No Importance (1893), and Ibsen's An Enemy of the People(1893). And in an effort to support new playwrights and plays with artistic rather than commercial value, he instituted special ‘Monday night’ performances restricted to the production of new dramas, essentially emulating Grein's work at the newly established Independent Theatre. He also elevated the Haymarket's status as a Shakespearian playhouse, and his productions of The Merry Wives of Windsor (1889), Hamlet (1892), and Henry IV, Part 1 (1896) earned him recognition not only as an accomplished actor–manager capable of producing a wide range of genres but also as a solid competitor to Henry Irving and the Lyceum Theatre.

Tree's successful career at the Haymarket enabled him to amass sufficient funds to finance in part construction of a new theatre, Her Majesty's Theatre (renamed His Majesty's with the accession of Edward VII in 1901), which opened on 28 April 1897 with Gilbert Parker's The Seats of the Mighty. During his management of Her Majesty's, from 1897 until his death in 1917, Tree staged approximately sixty plays, and the diversity of his repertory revealed his interest in classical drama as well as popular genres. In addition to producing contemporary poetic drama, such as Stephen Phillips'sHerod (1900), Ulysses (1902), Nero (1906), and Faust (1908), he staged plays by prominent British playwrights, including Henry Arthur Jones's Carnac Sahib (1899) and the London première of Shaw's Pygmalion (1914). Tree also produced and performed in a number of stage versions of popular nineteenth-century novels: Sydney Grundy'sMusketeers, an adaptation of Dumas's novel (1898); Henri Bataille and Michael Morton's remake of Tolstoy's work, Resurrection (1903); Morton's dramatization of Thackeray's novel The Newcomes entitled Colonel Newcome (1906); and three Dickensian adaptations, Oliver Twist (1905), The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1908), and David Copperfield (1914). In addition he offered his patrons adaptations of foreign plays, such as Louis Parker's Beethoven, a reworking of the play by Réné Fauchois (1909), Henry Hamilton's English version of Adolph Glass's A Russian Tragedy (1909), and W. Somerset Maugham's adaptation of Molière's Le bourgeois gentilhomme entitled The Perfect Gentleman (1913). The repertory at Her Majesty's included the classics, such as The School for Scandal (1909), as well as numerous melodramas, farces, and romantic comedies.

While Tree built Her Majesty's Theatre's solid reputation on the successful productions of a variety of dramas, he earned his theatre the international reputation as the premier playhouse for Shakespeare in Britain during the Edwardian era, and it is for this dedication to the production of Shakespeare that his career was most celebrated. During his twenty-year tenure at Her Majesty's he worked indefatigably to popularize Shakespeare with the general theatregoing public, and his success is evinced by an impressive production record unmatched by any West End manager: he put on sixteen Shakespeare plays which averaged initial three-month runs, many of them successful enough for periodic revivals during subsequent seasons, and he instituted an annual Shakespeare festival which featured more than two hundred performances by Her Majesty's Theatre company and other acting corps during its nine-year existence (1905–13). At a time when most theatre managers believed that Shakespeare's plays lacked commercial viability and spelt financial ruin, Tree proved that Shakespearecould be made accessible and appealing to large numbers of patrons. Fittingly, his initial Shakespearian production, Julius Caesar, was his first commercial success at Her Majesty's, and during its six-month run (22 January to 10 June 1898) it enjoyed 165 consecutive performances and attracted 242,000 spectators. His next revival, King John, ran from 20 September 1899 to 6 January 1900 and brought in 170,000 patrons, and he followed this with one of his most famous and successful comedies, A Midsummer Night's Dream, which played to 220,000 spectators from 10 January to 26 May 1900. Tree's longest running revival, Henry VIII, was a record breaker, receiving 254 consecutive performances from 1 September 1910 to 8 April 1911. Most of the Shakespeare revivals at Her Majesty's enjoyed equally unprecedented runs. Treesucceeded in popularizing Shakespeare with his audiences because he staged the plays in ways that appealed to spectators' taste for elaborate spectacle and realistic scenery and scenic effects. Working in the tradition of pictorial realism which dominated the nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century theatre, Tree brought this scenographic method to its apogee, staging the most spectacular Shakespearian revivals in British stage history. At Her Majesty's, audiences experienced unprecedented realistic stage pictures, such as the replica of a fourteenth-century list in Richard II (1903), the woodland glade with a shepherd's cottage and babbling brook in The Winter's Tale(1906), the storm-tossed sixteenth-century vessel in The Tempest (1904), the set of an authentic Renaissance ghetto in The Merchant of Venice (1908), or such interpolated scenes as Anne Bullen's coronation in Westminster Abbey and King John's granting ofMagna Charta. Tree's work with Shakespeare also involved four film projects that spanned his career at Her Majesty's: the opening shipwreck from his 1904 revival of The Tempest, captured on film at His Majesty's in 1905 by Charles Urban; a five-scene version of Henry VIII, based on his 1910 production featuring himself as Cardinal Wolsey, and filmed in February 1911 at William Barker's Ealing studio; a 1916 Macbeth, bearing no direct resemblance to his 1911 stage version, filmed in California by D. W. Griffith with Tree playing the title role; and, though not as extensive as the others but certainly the most important historically, three brief segments from his King Johnrevival filmed in 1899—Tree's initial cinematographic venture and the very first record of Shakespeare on film.

Tree excelled in character roles, and was considered by many to be the best character actor of his day. He possessed an exceptional mimetic genius that enabled him to enact a wide range of roles in which he gave each a unique and differing individuality, and he excelled especially in those characters with idiosyncratic and eccentric natures on which he could build strong, vivid parts, such as Svengali, Fagin, and Falstaff. His greatest strength was his inventiveness in delineating a character by the use of external details. As an expert with make-up, he could transform his nondescript, protean face into myriad roles which made the actor behind them virtually unrecognizable. Tree also had equal mastery over his facial expressions and body. He had remarkably expressive eyes which could project varying emotions within the character, from the dreamy languor of Hamlet during his moments of reflection and the baleful hatred of Shylock towards his persecutors to the nervous fear of Richard II during his surrender at Flint Castle. His hands were extraordinarily eloquent, and the gestures he used were always significant, telling, and illustrative. In addition, he could radically change his carriage and stature to effect a complete physical transformation into a character. Tree was tall, lanky, and graceful in gesture, but for his performance as Beethoven he transformed into a short, pudgy, bull-necked man with an awkward stride and jerky gestures. In selecting his Shakespearian roles he capitalized on these acting strengths by choosing parts that offered definable, observable, or atypical traits which could be made into strong character roles. His Malvolio was a swaggering and conceited fool, King John a superstitious and deceitful coward, and Macbeth a neurotic and self-torturing monarch. Tree built his characters slowly, allowing inspiration to suggest to him the appropriate business and external details, and he relied on that inspiration during performances, which could lead to inconsistent interpretations of a given role. Moreover, impatient and restless by nature, he easily tired of characters after a brief run, and, in an effort to sustain his own interest in a role, he continually added business and details to the part, which in turn led to further inconsistencies in his portrayals of a character over an extended time. The restlessness that spurred him on in his search for new, challenging, and various roles resulted in a degree of histrionic versatility that went unmatched by any of his contemporaries.

As a manager, Tree was regarded as Irving's successor and heir. Tree's theatre, built and decorated for him in the tasteful Louis XV style and deemed the handsomest playhouse in London, was, as Macqueen-Pope described it, 'the very essence of the Edwardian theatre' and 'the last word in everything theatrical at that time' (Carriages at Eleven, 31). Her Majesty's epitomized the cultural milieu of the Edwardian era in its opulence, and Tree's productions, with their elaborate and expensive scene designs, costumes, and properties, mirrored the Edwardian taste for luxury and extravagance. Towards the end of his career, Tree's production methods were being criticized by practitioners who favoured the new stagecraft of Appia and Craig's non-illusionistic sets and Poel's Elizabethanism, but Tree, one of the last major actor–managers to work along the lines of pictorial illustration, adamantly rejected the new scenography and defended his methods by referring his critics to the unprecedented attendance records and length of runs set at his theatre. His impressive managerial career at Her Majesty's, however, was not due solely to the spectacular scenery, for Tree offered his patrons a wide range of productions which could suit the different sensibilities and tastes of most Londoners. Most importantly, he appreciated the need for a strong acting ensemble, and, unlike Irving, he commissioned the best actors to join his company. His productions featured such renowned performers as Constance Collier, Ellen Terry, Madge Kendal, Julia Neilson, Violet Vanbrugh, Oscar Asche, Arthur Bourchier, and Lewis Waller. In every aspect of production Tree hired the most expert artists available, including designers (Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Joseph Harker, Walter Hann, Percy Anderson) and musicians (Raymond Roze, Arthur Sullivan, Coleridge Taylor) who helped create, under his direction, some of the most magnificent and artistic theatre productions of the Edwardian era.

Tree's management at the Haymarket and Her Majesty's was aided by his wife, Maud, who viewed their union as a theatrical partnership as well as a personal one. In addition to acting in numerous revivals under her husband's direction, Maud Tree lent encouragement and advice on many of his projects and productions, and her support was a significant contributing factor to his continued success. The professional success earned by their partnership gained them and their three daughters entrée into London's élite society: the Tree family became intimately acquainted with some of the most socially prominent and politically powerful members of Edwardian society, including members of parliament and the peerage, as well as London's coterie of élite intellectuals and aesthetes, ‘the Souls’, particularly the family of Violet Manners, duchess of Rutland. Viola, Felicity, and Iris Tree were fully absorbed by aristocratic society: Iris married Curtis Moffat, becoming Countess Ledebur, and Felicity married Sir Geoffrey Cory-Wright, third baronet. Viola followed the family profession, and eventually married Alan Parsons, a theatre critic.

Tree made significant contributions to the growth of the British theatre and the advancement of theatre art. In 1904 he established the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, which remains one of the most prestigious schools for stage training in the world. He also served as president of the Theatrical Managers' Association and worked in various capacities for the Actors' Benevolent Fund and the Actors' Association. For all these contributions, as well as for his work at Her Majesty's, he was knighted by Edward VIIin 1909. His renown in the theatre world earned him invitations to tour his revivals in America, which he did on numerous occasions, and brought him a special invitation from the German Kaiser, to which he responded by performing with his company in various Shakespearian plays at Berlin's Royal Opera House (1907). He also received invitations to lecture on theatre in Great Britain and America; during the war years, he used these opportunities to deliver patriotic addresses. He wrote several books in which he discussed the importance of the theatre and the arts in modern society.

Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree died on 2 July 1917, at a London nursing home at 15 Henrietta Street, Marylebone, from pulmonary blood clots after undergoing surgery for a leg injury. He was survived by his wife and three daughters, and also by six children from his liaison with (Beatrice) May Pinney (later Reed): among these children were the film director Carol Reed and Peter Reed, the father of the film actor Oliver Reed. His body was cremated and his ashes were placed in Hampstead cemetery.

- B. A. Kachur DNB

Frank Haviland was a painter of miniatures, figure subjects and portraits. He lived in London and exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1894-1910