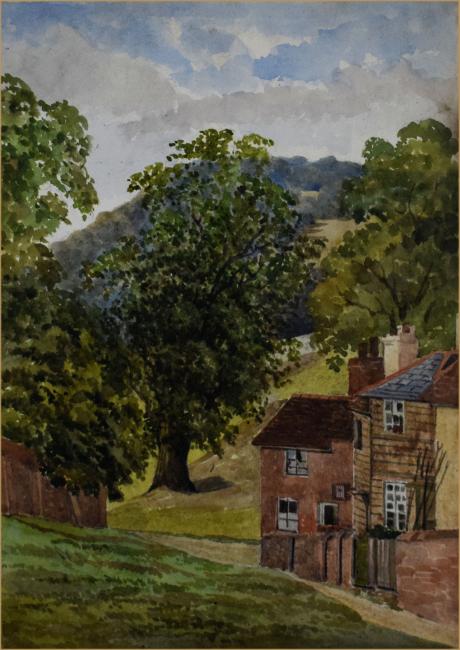

inscribed and dated in the margin "Boxhill from the Dene, Dorking , 1898"

Box Hill is a summit of the North Downs in Surrey, approximately 30 km (19 mi) south-west of London. The hill gets its name from the ancient box woodland found on the steepest west-facing chalk slopes overlooking the River Mole. The western part of the hill is owned and managed by the National Trust, whilst the village of Box Hill lies on higher ground to the east. The highest point is Betchworth Clumps at 224 m (735 ft) above OD, although the Salomons Memorial (at 172 metres) overlooking the town of Dorking is the most popular viewpoint. Box Hill lies within the Surrey Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and forms part of the Mole Gap to Reigate Escarpment Site of Special Scientific Interest. The north- and south-facing slopes support an area of chalk downland, noted for its orchids and other rare plant species. The hill provides a habitat for 40 species of butterfly, and has given its name to a species of squash bug, now found throughout south-east England.

An estimated 850,000 people visit Box Hill each year. The National Trust visitors' centre provides both a cafeteria and gift shop, and the panoramic views of the western Weald may be enjoyed from the North Downs Way, a long-distance footpath that runs along the southern escarpment. Box Hill featured prominently on the route of the 2012 Summer Olympics cycling road race events (the men doing nine circuits and the women doing two circuits).The hill was purchased by Thomas Hope, shortly before his death in 1831. (Hope was the owner of The Deepdene, the mansion to the east of Dorking.) The Mickleham Parish Records credit Hope's widow, Louisa de la Poer Beresford (whom he had married six years previously), with allowing "free access to the beauties of this hill," however day-trippers had been arriving in significant numbers for at least a century before that.

Developments in local transport infrastructure over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, enabled increasing numbers to visit the area. Following the completion of the turnpike road between Leatherhead and Dorking in 1750, stagecoaches stopped regularly at the Burford Bridge Hotel. As late as 1879, a daily coach ran non-stop to Box Hill from Piccadilly with a journey time of 2.5 hours. The South Eastern Railway opened the first railway station in Dorking in 1849, followed in 1867 by the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LBSRC), which opened the station in the village of Westhumble.The LBSCR ran dedicated excursion trains to Box Hill on Bank Holiday weekends and over 1300 day-trippers were recorded arriving at Westhumble station on 6th August 1883.

The Old Fort, constructed in 1896. Note the earth blast bank (left) which protects the south west face of the flat-roofed main building (right).

In the latter half of the 19th century, growing public concern over the ability of the British armed forces to repel an invasion (stoked, in part, by the serialisation of George Tomkyns Chesney’s 1871 novella The Battle of Dorking), prompted the government to announce the construction of thirteen fortified mobilisation centres, collectively known as the London Defence Positions. A 6-acre (2.4 ha) site was purchased from the trustees of the Hope estate by the Ministry of Defence in 1891, and construction began in 1896. Box Hill fort was laid out in the form of an infantry redoubt, typical of the period, but also included magazines for the storage of artillery ammunition. (In common with the majority of the twelve other mobilisation centres, the Box Hill fort was designed for the use of the infantry only and the stored ammunition was intended for the use of mobile field artillery which would be deployed nearby as required.The fort is aligned on a NW-SE axis and is a reinforced concrete structure faced with brick. The building had a flat roof and is protected from artillery fire by a crescent-shaped earth blast bank, which is surrounded by an outer ditch.

A reform of defence policy by the Secretary of War Viscount Haldane in 1905 resulted in all 13 centres being declared redundant, and Box Hill Fort was sold back to the estate trustees in 1908.] A metal grill has been placed over the entrance to allow bats to access to their roosts and the structure has Grade II listed status.

Back in the 1800s, this famous connoisseur and collector spent many years developing Dorking’s The Deepdene into what Disraeli would describe as ‘the most perfect Italian palace you can conceive’, set in ‘the most romantic grounds and surrounded by the most picturesque park I can well remember’. Today, this magnificent estate has been largely forgotten, the house long-gone and the grounds overgrown – but now, thanks to a Heritage Lottery Grant awarded earlier this year, an ambitious restoration project is under way. Dubbed ‘Hope Springs Eternal’, it will see part of the grounds open to the public for free, as part of a new trail, from this time next year.

It’s also the reason I find myself standing in a car park, alongside Kuoni HQ, on a sunny autumnal day, equipped with notepad, camera and walking boots. “What happened here shaped fashionable taste across the nation,” says project manager and historian, Alexander Bagnall, as he prepares to show me around this historic site.

“Queen Victoria’s Osborne House was derived from Hope’s mansion; Disraeli wrote his novel, Coningsby, while staying here; and the park also caught the imagination of composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, who successfully campaigned to rescue it from development.“At one point, the dowager Duchess of Marlborough rented the estate and her nephew, a certain Sir Winston Churchill, often visited as a young man – and then again, through the war years, as troop movements to Dunkirk were organised from this area. So we’re walking in famous footsteps…”

Such grand times and yet, in the end, the A24 bypass was built for the town in the 1930s (apparently one of the first bypasses in the country), which largely put paid to the estate’s gardens, while the property itself became home to Southern Railway.Eventually, like so many of our great country houses, the mansion was demolished in 1967 – and bar the family mausoleum, which was buried to roof level in earth, to protect it from vandals, it seemed that hope was gone.? “It’s amazing just how few people knew that this area was so significant – and even for those who knew it was here, it’s largely been off-limits,” says Alexander.“When we first started working on it, you couldn’t really see the gardens as they were completely covered by rhododendrons. With volunteers, we’ve been working to old photographs and tentatively peeling back the layers. It’s extremely exciting to see some of the original pathways and vistas slowly reveal themselves as we work.”

Today, I’ll only be visiting the Deepdene Gardens and Hope Mausoleum sites, but The Deepdene Trail, as it will be known, will eventually spread across the full breadth of the former estate as far as the villages of Brockham and Betchworth. When complete, there will be guided walks and mobile apps ready to recreate the landscapes and fill in the gaps that the imagination might struggle with (Kuoni’s headquarters sits within the footprint of the demolished Deepdene mansion, for instance). What surprises me most of all, perhaps, is that where I was expecting to traipse through the hills for a while in search of Hope, just one step off the car park’s tarmac leads us into the Deepdene Gardens.

“People have sat around here having lunch on park benches for years, probably not realising that where they are sitting is potentially an international treasure – the Thomas Hope exhibition at the V&A a few years ago saw huge interest around the world,” says Alexander, as he leads me through the garden’s ‘amphitheatre’ to the grotto; a low, bunker-like structure that has seen many incarnations over the years.

“What’s incredible is that when you pop inside the grotto, you can literally see history,” he continues. “It’s got the original 1780s floor, decorations from its various stages and then, when you look at the walls at the back, the layers have been opened up so you can see four different eras. “Originally, the grotto – and the temple that would have stood at the top of the steps above it – would have provided a perfect symmetry to the vista, which then ran from hillside to hillside with little to interrupt it. Some beautiful watercolours still exist today.”

Continuing on away from the grotto, and along the original paths that have been rediscovered by attentive volunteers, we head first to the terrace above (and up those steps with Vaughan Williams to thank) and then back through the woods to the remnants of the grandly-named Embattled Tower, which has a mystique all of its own, despite being rather scaled down from its original grandeur. “There was a time where we were losing two country houses a week in the 1960s and ‘70s, which is a catastrophic rate,” continues Alexander. “Clearly, they were extremely expensive to run, so a lot of them very sadly fell into disrepair. “One of our wonderful volunteers, who is in his 80s now, remembers the house here and says that you couldn’t even go out onto the balcony, for instance, because it was in such a state of disrepair that it would collapse.”

For all that, we are lucky that The Deepdene estate has at least maintained some of its essence, meaning that those clearing the undergrowth away continue to uncover remnants and pointers that match the beautiful paintings captured during its heyday. “Also, with the Hope Mausoleum, it’s incredible that we have this pure architectural space that remains as Hope intended it,” adds Alexander, as we cheat our way via car over to the next – and most famous – site on the new trail by Dorking Golf Club. “When something is almost completely lost, it really fires your imagination, and we’re lucky because we have enough in the archives and in reality to make the whole project tangible.”

The mausoleum is such an imposing edifice, it seems incredible that until only recently golfers chasing errant balls would have no idea it was there. Commissioned by Thomas Hope, following the death of his seven-year-old son Charles of a fever on a visit to Rome, Hope was also later buried here.“What makes mausolea so interesting is that they’re such a pure expression of architectural interest,” says Alexander. “By their very nature, you don’t have to worry about living quarters, windows etc, and so there are many great architects who loved to design them. With this, the only complete fragment from Hope’s time, it’s actually extremely fitting. Mausolea were hugely popular in the Victorian era, for instance, as a place for quiet reflection – they weren’t seen as morbid at all.”

That such a special location needed to be unearthed at all rather sums up the importance of what is going on in this corner of Dorking.

In many ways, my visit reminds me of seeing pictures of Cobham’s Painshill Park, or the Lovelace Bridges in Horsley, before hardened volunteers set about reclaiming the heritage from overgrowth and decay. So, all being well, this new Deepdene Trail is set to add yet another bow to this area’s burgeoning appeal (with Denbies, Box Hill and the like on the doorstep) as a new destination for future potential ‘grand’ tours, and that’s something we can all hope for.