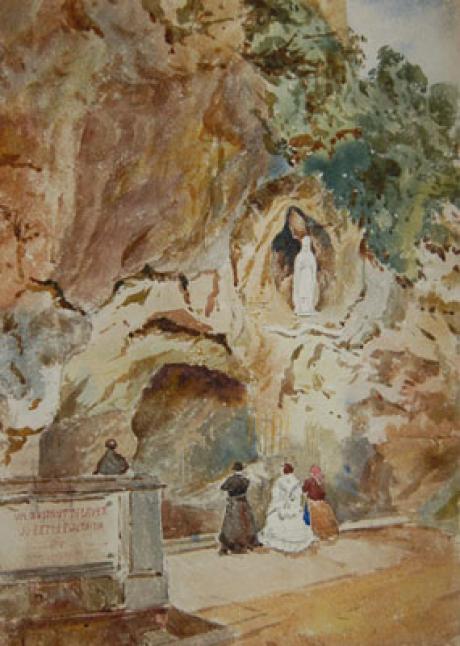

"L.....aters Grotto /Lourdes/Oct 13 1869"

Our Lady of Lourdes is the name used to refer to the Marian apparition that appeared before various individuals in separate occasions around Lourdes, France. The apparitions of Our Lady of Lourdes began on 11 February 1858, when Bernadette Soubirous, a 14-year-old peasant girl from Lourdes admitted, when questioned by her mother, that she had seen a "lady" in the cave of Massabielle, about a mile from the town, while she was gathering firewood with her sister and a friend.[1] Similar appearances of the "lady" took place on seventeen further occasions that year. Bernadette Soubirous was canonized as a saint, and many Christians believe her apparitions to have been of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Pope Pius IX authorized the local bishop to permit the veneration of the Virgin Mary in Lourdes in 1862.

On 11 February 1858, Bernadette Soubirous went with her sisters Toinette and Jeanne Abadie to collect some firewood and bones in order to be able to buy some bread. When she took off her shoes and stockings to wade through the water near the Grotto of Massabielle, she heard the sound of two gusts of wind (coups de vent) but the trees and bushes nearby did not move. She saw a light in the grotto and a girl, as small as she was, dressed all in white, apart from the blue belt fastened around her waist and the golden yellow roses, one on each foot, the colour of her rosary. Bernadette tried to keep this a secret, but Toinette told her mother. After parental cross-examination, she and her sisters received corporal punishment for their story. Three days later, Bernadette returned to the Grotto with the two other girls. She had brought holy water as a test that the apparition was not of evil provenance, however the vision only inclined her head gratefully when the water was thrown. Bernadette's companions reportedly became afraid when they saw her in ecstasy. Bernadette remained ecstatic when they returned to the village. On 18 February, she was told by the Lady to return to the Grotto over a period of two weeks. The Lady allegedly said: I promise to make you happy not in this world but in the next. After the news spread, the police and city authorities began to take an interest. Bernadette was prohibited by her parents and police commissioner Jacomet to ever go there again, but she went anyway. On 24 February the apparition asked for prayer and penitence for the conversion of sinners. The next day, Bernadette was asked to dig in the ground and drink the water of the spring she found there. This made her dishevelled and caused dismay among her supporters, but revealed the stream that soon became a focal point of pilgrimage. At first muddy, the stream became increasingly clean. As word spread, this water was given to medical patients of all kinds, and numerous miracle cures were reported. Seven of these cures were confirmed as lacking any medical explanations by Professor Verges in 1860. The first person with a “certified miracle” was a woman, whose right hand had been deformed as a consequence of an accident. Several miracles turned out to be short-term improvement or even hoaxes, and Church and government officials became increasingly concerned.The government fenced-off the Grotto and issued stiff penalties for anybody trying to get near the off-limits area. In the process, Lourdes became a national issue in France, resulting in the intervention of emperor Napoleon III with an order to reopen the grotto on 4 October 1858. The Church had decided to stay away from the controversy altogether.

Bernadette, knowing the localities rather well, managed to visit the barricaded grotto under the protection of darkness. There, on March 25, she was told: " I am the Immaculate Conception" ("que soy era immaculada concepciou"). On Easter Sunday, 7 April, her examining doctor stated that Bernadette, in ecstasy, was observed to have held her hands over a lit candle without receiving any burns. On 16 July, Bernadette went for the last time to the Grotto. I have never seen her so beautiful before. The Church, faced with nation-wide questions, decided to institute an investigative commission on 17 November 1858. On 18 January 1860, the local bishop finally declared that: The Virgin Mary did appear indeed to Bernadette Soubirous. These events established the Marian veneration in Lourdes, which together with Fátima, is one of the most frequented Marian shrines in the world, and to which between 4 and 6 million pilgrims travel annually.

The verity of the apparitions of Lourdes is not an article of faith for Catholics. Nevertheless all recent Popes visited the Marian shine. Benedict XV, Pius XI, and John XXIII went there as bishops, Pius XII as papal delegate. He also issued with Le Pelerinage de Lourdes a Lourdes encyclical on the hundredth anniversary of the apparitions in 1958. John Paul II visited Lourdes three times and Pope Benedict XVI completed a visit there on 15 September 2008 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the apparitions in 1858

The Rev John Louis Petit (1801–1868), architectural historian and watercolour painter, was born on 31 May 1801 in Ashton under Lyne, Lancashire, the only son of John Hayes Petit (1771–1822), a Church of England clergyman and JP, and his wife, Harriet Astley.

The family was descended from Lewis Petit, also known as Lewis Petit des Etans (1665?–1720), a Huguenot refugee and military engineer. Petit's grandfather was John Lewis Petit (1736–1780), the son of John Petit of Little Aston Hall, Shenstone, Staffordshire. He graduated from Queens' College, Cambridge (BA 1756, MA 1759, and MD 1766), was elected fellow of the College of Physicians in 1767, was Gulstonian lecturer in 1768, and was censor in that year, 1774, and 1777. From 1770 to 1774 he was physician to St George's Hospital, then on the death of Dr Anthony Askew in 1774 he was elected physician to St Bartholomew's Hospital. In November 1769 he married Katherine Laetitia Serces, the daughter of one of the preachers of the French Chapel Royal in London. He died on 27 May 1780 and was buried at St Anne's, Soho. John Louis Petit was educated at Eton College and contributed to The Etonian, then in its heyday. He was elected to a scholarship at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1822, and graduated BA in 1823 and MA in 1826. On 17 June 1828 he married Louisa Elizabeth, the daughter of George Reid of Trelawny, Jamaica. He had been ordained deacon in 1824 and priest the year after, but it was not until 1840 that he took up his sole church appointment, as curate of Bradfield in Essex, which he held until 1848. By this time he had written and illustrated several works of architectural history, the main occupation of his career.

Petit had shown a taste for sketching in his early years and he made many hundreds of drawings in pencil and ink. These were often finished in watercolour, though in a limited palette. His favourite subject was old buildings, particularly churches, and he spent much time visiting and sketching them. His drawings were rapidly and adeptly executed on the spot, his style in the tradition of English topographical watercolour painters of the previous generation, such as Samuel Prout (1783–1852). Although his works display an instinct for the picturesque setting and the telling viewpoint, his aim was less to produce finished paintings for their own sake than to record historic buildings and architectural details. Many were reproduced in his profusely illustrated books. He occasionally painted in oils. In almost all of these respects he resembles John Ruskin (1819–1900), whose concern for the conservation of old buildings was Petit's too. In 1839 Petit made his first extensive tour on the continent, which informed his Remarks on Church Architecture (1841), part travelogue, part discursive survey of architectural styles since the Roman. Subsequent works provide more detailed analyses of individual buildings, including Tewkesbury Abbey, Sherborne Abbey, and Southwell Minster. Petit's credentials as an antiquary are reflected in his co-founding of the British Archaeological Institute in 1844 and his elections as fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and honorary member of the Institute of British Architects. He lectured to the Oxford society for promoting the study of Gothic architecture, a body which mirrored the Cambridge Camden Society and whose membership similarly took a deep interest in the way churches old and new should be laid out and used. This Oxford connection was fruitful academically for Petit, who was admitted to the university ad eundem in 1850, and personally too, as his sister, Maria, married a classics don, William Jelf (1811–1875), in 1849. Architectural Studies in France, Petit's principal work, appeared in 1854 (new edition 1890). It is a detailed survey of French Gothic, profusely illustrated by Petit and by his companion on the research tour, Philip Delamotte (1820/21–1889), an artist, engraver, and early exponent of photography. Petit does not seem to have used photography for recording buildings; nevertheless, some of the illustrations were reproduced using a new technique, that of anastatic drawing.

Petit's books come from a rich period in England for research, publication, and debate on architectural history. His writing style was accessible and the illustrations attractive, but he lacked the intellectual rigour of others in the field, such as his Cambridge contemporaries William Whewell (1794–1866) and Robert Willis (1800–1875). His judgements could be shaky and, with his genteel admiration of almost anything old, he could elicit harsh reviews at a time when attitudes were hardening in favour of particular styles as models for revival. While he had a taste for the Romanesque, for example, just before it became fashionable as a style for new churches in the 1840s, he did not make himself its champion. He was not a polemicist like A. W. N. Pugin or George Gilbert Scott; besides, he had a distaste for debates that smacked of religious controversy. This was the tendency from the 1840s, particularly in the pages of The Ecclesiologist, the organ of the Cambridge Camden Society.

When Petit did turn his attention to contemporary architectural practice, he encountered spirited opposition. In 1841 Scott's designs for the remodelling of St Mary's, Stafford, were exhibited. This was a church close to Petit's heart (his brother-in-law was a benefactor) and he objected in writing to the proposal for the thoroughgoing redesign of the south transept. He could accept Scott's interventions elsewhere in the building but not so the replacement of Gothic fabric, albeit sixteenth-century. Scott accepted the principle but argued that it could be ignored if the style was ‘debased’. Their debate by correspondence was eventually put to a panel of experts from the Cambridge Camden Society and the Oxford society noted above. Scott won and Petit gamely published the papers. As galling was the reception of Petit's only executed architectural design. His sister and brother-in-law moved to Cae'rdeon, near Barmouth, Merioneth, in 1854. Jelf took exception to the fact that most of the services in the Anglican parish church were said in Welsh, so in 1862 he asked his brother-in-law to design him a church, to be built at his own expense, where he could officiate in English. Petit designed him a rugged and muscular church for the mountainous setting. The Ecclesiologist lambasted it in a pithy review, attacking the design on practical grounds (roof pitches too shallow) and on theoretical grounds (pilasters for show, not structural necessity). The critic is clearly exasperated that Petit preferred picturesque effect to the application of formal principles: the alpine-style stone hut is simply not appropriate for an Anglican church on a turnpike road. There may also be a difference of churchmanship here. Petit and Jelf (for all his belligerence on the language issue) had avoided the febrile excesses of the Oxford Movement. Happily, St Philip Cae'rdeon still stands, somewhat altered but recently repaired.

During 1864–5 Petit travelled to Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. He continued to draw and paint avidly. He died in Lichfield on 1 December 1868 from a cold caught or aggravated while out sketching, and was buried in St Michael's churchyard. An exhibition of 339 of his sketches, including two views of the church at Cae'rdeon, was shown by the Architectural Exhibition Society in London during 1869. That year also saw the posthumous publication of a volume of his poetry. Sir Nikolaus Pevsner gives a characteristically pungent account of Petit in his survey of nineteenth-century architectural writers. As an artist, his modest talent was given almost unlimited scope, producing a corpus of architectural impressions which is impressive, if slight as individual works of art. As a critic of contemporary practice, he is probably most significant as a spokesman for tolerance: he valued buildings and styles of many eras and favoured, if not consistently or dogmatically, repair over rebuilding.