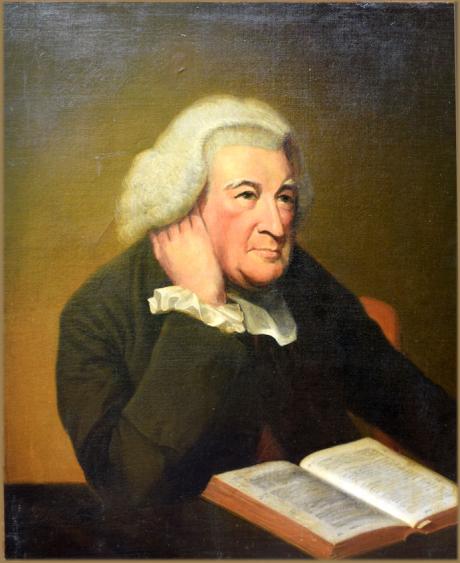

Markham, William (bap. 1719, d. 1807), archbishop of York, was baptized at Kinsale, in the county of Cork, on 9 April 1719, the eldest of the four children of Major William Markham (d. 1771) and his wife, Elizabeth (1686–1772), a distant cousin and the daughter of George Markham of Worksop Lodge, Nottinghamshire. His father was an army officer of literary tastes who ran a school to supplement his half pay. The family claimed descent from the Markhams of Cotham.

After early education at home from his father Markham was admitted to Westminster School as a home boarder on 21 June 1733; there his academic talents were complemented by skills as an oarsman and a boxer. In 1738 he obtained a studentship at Christ Church, Oxford, and matriculated on 6 June 1738. He took the degrees of BA (13 May 1742), MA (28 March 1745), BCL (20 November 1752), and DCL (24 November 1752). He held the college lectureship in rhetoric from 1747 to 1750 and was appointed junior censor the following year. Markham's literary talents and wide-ranging classical scholarship flowered during these years at the house. His ‘Judicium paridis’, a Latin verse version of Shakespeare's ‘Seven Ages of Man’, was published in volume 2 of Vincent Bourne's Musae Anglicanae in 1741, while other specimens of his Latin verse appeared in the second volume of Carmina quadragesimalia (1748).

After ordination and continental travel Markham followed his father's example and took up teaching. In 1753 the headship of Westminster School fell vacant on the retirement of Dr John Nicholl, and Markham's familiarity with the school and his high academic standing secured him the post. There he remained for the next eleven years, taking what the Public Advertiser in 1755 called ‘the first Seminary of School Learning in Europe’ through its two hundredth anniversary in 1760. Markham established a reputation as one of the most formidable headmasters of the eighteenth century, though more for his managerial than for his pedagogical skills. Teaching was never Markham's first priority but he had an undeniable presence in the classroom. One of his pupils, Jeremy Bentham (Westminster, 1755–60, and himself the son of a Christ Church canon), famously described Markham in the form room as ‘an object of adoration’ (Works of Jeremy Bentham, 10.30). Many other members of the later Georgian élite received their schooling at his hands. Without personal wealth or high birth Markham sedulously but never fawningly cultivated the powerful throughout his life. He watched over the interests of former pupils, while many of them tended his.

Markham meanwhile accumulated church preferments, thanks to the friendly interest extended by that old Westminster, the duke of Newcastle. He was appointed chaplain to George II in 1756, and Bishop Richard Trevor nominated him to the second prebendal stall in Durham Cathedral on 22 June 1759 (installed 20 July). There were murmurings that the headmaster was putting personal interests before those of the school, and indeed by 1763 Markham was angling for a crown appointment. He eventually resigned the headmastership (pleading ill health) on 8 March 1764 but only received a fresh post towards the end of the Grenville ministry when the Rochester deanery fell vacant. Markham was instituted as dean on 20 February 1765 and in the same year was presented by the chapter to the vicarage of Boxley, Kent. His stay at Rochester was brief. The death of David Gregory in September 1767 offered an opening for Markham to return to Christ Church, and he exchanged one deanery for another the following month with the blessing of both Newcastle and Archbishop Secker. Thus began a decade in academic office which saw Markham at his most creative as a teacher and administrator. He brought to Christ Church some of his best former pupils at Westminster and strengthened the historic connection between the two institutions. He had ambitious reform plans for the college which he summarized for Charles Jenkinson: ‘My great object is to bring the noblemen and gentlemen commoners to the same attendance on College duties, and the same habits of industry with the inferior members’ (11 Jan 1768, BL, Add. MS 38457, fol. 11). Such changes added signally to the college's reputation, along with the institution of public lectures, the addition of new authors to the curriculum in Greek studies and ancient history, and the reform of ‘collections’ to underpin the programme as a whole.

It was not long before the ambitious dean enhanced his status further with a bishopric, thanks to the sponsorship of Lord Mansfield. Markham succeeded Edmund Keene as bishop of Chester and was consecrated on 17 February 1771 at the Chapel Royal, Whitehall; he thereupon resigned Boxley and his Durham prebendal stall but retained the Christ Church deanery in commendam until 1777 to supplement the £1000 annual income derived from Chester. Markham became a non-resident prelate with responsibility for a huge diocese despite minimal pastoral experience. He made a visit to Chester every summer and confirmed extensively but otherwise his diocesan duties took their place alongside his other responsibilities.

Markham's friendship with Lord Mansfield and his pedagogic reputation secured him the post of preceptor to the young prince of Wales and his brother Prince Frederick, bishop of Osnaburg, on 12 April 1771 (Walpole, Memoirs, 4.311). After five years in that difficult role Markham left office in May 1776 in the ‘nursery revolution’ precipitated by the resignation of the boys' governor, Lord Holdernesse. Markham took the side of Cyril Jackson, his sub-preceptor, in his disagreement with Holdernesse. The prince of Wales had got on well with Markham's family and wanted the bishop to remain in post. George III, however, would not make this concession to the wishes of his son, whom he saw as primarily responsible for the affair. The prince remained on very cordial terms with Markham for the rest of his life.

Compensation from the crown was not long delayed. Markham's appointment to the archbishopric of York was announced on 21 December 1776 (enthroned by proxy 28 January 1777). He was also appointed lord high almoner and sworn of the privy council. Within weeks of having received office Markham, on 21 February 1777, had preached a sermon before the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (in the parish church of St Mary-le-Bow) on the calamities that had overtaken Anglicans in the American colonies, and had argued for deploying the machinery of state to assist the spread of Christianity. The sermon was interpreted by opposition politicians as a bellicose endorsement of the government's coercive policy, and Markham found himself at the centre of a political storm for his alleged high-flown monarchism and veiled threats to dissenters. On 30 May in the House of Lords, Markham replied ‘with great warmth’ to the attacks made on him by the duke of Grafton and Lord Shelburne for preaching doctrines allegedly subversive of the constitution—‘pernicious’ doctrines, according to Lord Chatham's subsequent denunciation (Cobbett, Parl. hist., 19.327–8, 344–50, 491). Markham received much private support from close friends like Viscount Stormont, who was delighted that his sermon opposed the ‘senseless licentious sophistry’ of the day ‘with all the Powers of Reason enforced by that irresistible Eloquence that Virtue alone bestows’ (letter, 21 May 1777, Mansfield muniments, National Register of Archives for Scotland, 0220). Markham derived only limited comfort from this backing. He was enduringly offended by the insults and was one of the four peers who signed the protest against the third reading of the Chatham annuity bill on 2 June 1778 (Rogers, 2.177–8).

After this incident Markham's conduct in parliament was more circumspect and he rarely spoke in the Lords. He supported Lord North's administration until its fall in 1782, and subsequently that of Pitt the younger, but his defence of Anglican interests was low key and private; he had no wish to draw on himself afresh the public hostility that had undoubtedly damaged his standing. Even so Markham's personal courage was never in doubt. En route for the House of Lords on 2 June 1780 he was attacked by the protestant petitioners and, subsequently hearing of Lord Mansfield's danger, he tore down from a committee room to rescue his friend. His town house in Bloomsbury Square adjoined that of the lord chief justice; in a letter to his son John, Markham offers a graphic description of the attack on Mansfield's property by the Gordon rioters, and of his own narrow escape from the violence of the mob (D. F. Markham, 60–65).

John Markham, who rose to the rank of admiral of the blue, was the second son of Markham and his wife, Sarah (1738–1814), daughter of John Goddard, a wealthy English merchant of Rotterdam, whom he had married on 16 June 1759 (the settlement was worth £10,000). They had a large family of six boys and seven girls, of whom eleven survived. Markham was known as an affectionate family man and Bishopthorpe had an atmosphere ‘of kindness and good-humour’ in his time (Warner, 1.295). He put much effort into finding professions or eligible marriage partners for his children. The eldest child, William (d. 1 Jan 1815), was appointed private secretary to his father's school contemporary Warren Hastings. This connection inextricably involved the Markham family in the impeachment of the former governor-general before the House of Lords. Markham made no secret of his support for Hastings and once again drew criticism from the whig opposition. On 25 May 1793 he interrupted Burke's cross-examination of defence witnesses to accuse the managers of treating James Peter Auriol, former secretary to the supreme council and a relative of Archbishop Robert Hay Drummond, as no better than a pickpocket. He went on: ‘if Robespierre and Marat were in the Managers Box they could not say any thing more inhuman and more against all sentiments of honor and morality’ (BL, Add. MS 24243, fol. 56). Markham was highly agitated. His daughter Georgina was dying, and that fact curtailed discussion of his intervention in the House of Commons. The archbishop was undeterred from complaining again about the conduct of the trial; on 24 March 1795 he declared that Hastings had been ‘treated not as if he were a gentleman, whose cause is before you, but as if you were trying a horse-stealer’ (Bond, 4.lxi). He was one of only three prelates to vote Hastings not guilty on all charges, and his staunch support for Hastings wrecked what little remained of his friendship with Edmund Burke.

Markham's thirty-year tenure of the York archdiocese was one of modest distinction. To York Minster he gave new velvet coverings for the high altar, pulpit, and archbishop's throne, and he also encouraged repairs at Ripon and Southwell minsters. His visitational activities were restricted by comparison with predecessors like Drummond and Thomas Herring (there were none after 1791), a fair reflection of his pastoral limitations. Respected for his integrity and sense of honour rather than loved by his clergy he took some time to overcome the rumpus caused by his early public criticism of those priests who had joined the associating movement for parliamentary and economical reform. He devoted much energy to securing key positions in the see for his sons; George was appointed dean of York in 1802, Robert held the archdeaconry of York, and Osborn was named chancellor of the diocese in 1795. Such nepotism was conventional in the late Georgian church, Markham had a large family to provide for, and his status as senior archbishop in England after 1783 and through the war years with France was unassailable. He held back from a conspicuous metropolitan role but was uncompromising in his assertion of the rights of the established church. Markham was not an inspired spiritual leader. As one obituarist closely observed: ‘His religion was a religion of the mind; practised in all the concerns of life, without austerity, and free from ostentation’ (GM).

Markham died at his house in South Audley Street, London, on 3 November 1807, and was buried on the 11th in the north cloister of Westminster Abbey, where a monument was raised to his memory by his grandchildren (he had no fewer than fifty, and three great-grandchildren). His widow died in Mortimer Street, Cavendish Square, London, on 26 January 1814, aged seventy-five, and was buried beside him on 3 February. Throughout his life Markham retained a headmasterly presence that could, to his political opponents, appear overbearing and pompous; to his friends it recalled his father's martial bearing and was well suited to the dignity of the offices he filled. Beneath the surface was a man of strong emotions which occasionally, as in the trial of Warren Hastings, broke through, often in the form of petulance. The elder Richard Burke told his nephew that Markham's ‘manner exceeded the matter. Such furious agitation, and bodily convulsion, not producing death were wonderful’ (Correspondence, 7.369). In the 1770s, because of his political allegiances, he was the butt of a number of satirical cartoons. Unfortunately for Markham historians have turned first to Horace Walpole's unflattering view of him: ‘a pert, arrogant man’, as the Memoirs of the Reign of George III describes him (4.206), that ‘warlike metropolitan archbishop Turpin’ (Walpole, Corr., 28.313). A much fairer assessment was offered by Samuel Parr, no political ally of Markham's, who singled out inertia for preventing the prelate from making that mark on British public life, either as a scholar or as an archbishop, to which his native abilities entitled him: his ‘powers of mind, reach of thought, memory, learning, scholarship, and taste were of the very first order, but he was indolent, and his composition wanted this powerful aiguillon’ (D. F. Markham, 66). Apart from his verse, Markham published only sermons.

Nigel Aston DNB

Ward, James (1769–1859), painter and printmaker, was born on 23 October 1769 in Thames Street, London, the middle of five children of James Ward, fruit merchant, and his wife, Rachael (1736/7–1835). He was baptized at All Hallows-the-Great, Upper Thames Street, on 12 November, that same year.

Early life and training

Ward's father was intemperate in his habits, and, as a result, at the time of James's birth the family's fortunes had declined. Although his elder brother, William Ward, attended school, Ward did not, and in later years he was self-conscious about his lack of formal education. When he was twelve he was apprenticed, like his brother William, to the engraver John Raphael Smith, although Ward subsequently claimed that he had little encouragement from his master, and his apprenticeship was terminated after fewer than two years because of problems between them. He completed his indenture with his brother. It was during his apprenticeship to Smith that James demonstrated his artistic ability, reportedly reproducing from memory a drawing by Henry Fuseli. The few extant drawings from this period attest to his youthful skills.

From the outset of his career Ward was a successful and highly respected mezzotint engraver of works by other artists. However, engravers were not eligible for election to the Royal Academy, and Ward therefore decided to abandon his lucrative career as an interpreter of the works of others and to dedicate himself to painting. The artists who employed Ward tried to persuade him to remain a printmaker, and he continued to create prints, especially after his own compositions; in the 1820s he also became a very accomplished lithographer. Ward donated a large collection of his prints in various states to the British Museum. In 1794 he was appointed painter and engraver in mezzotint to the prince of Wales. On 4 December he married Mary Ann Ward (d. 1819; no relation) at the parish church of St Marylebone, London.

Of the several children of James and Mary Ann Ward, George Raphael Ward (1799–1878) became a painter and engraver. He was born on 17 July 1799 and was baptized on 8 November that year at St Mary's, St Marylebone Road. After studying under his father in 1822 he entered the Royal Academy Schools, when his age was given as twenty-one. The following year he won a silver medal at the Society of Arts and continued to exhibit, particularly at the Royal Academy and New Water Colour Society until 1864. On 30 December 1827 he married Mary Webb, with whom he had a daughter, Henrietta Mary Ada Ward (1832–1924), also an artist, who became the wife of Edward Matthew Ward (1816–1879), historical genre painter. George Ward became a miniaturist and engraver, and made copies in miniature after portraits by Sir Thomas Lawrence. He signed these G. R. Ward and on some gave his address as 7 Newman Street, Oxford Street. Foskett commented of that ‘at its best [his work] is good’, his ‘colours pleasant with blue-grey shadows’; some works, she noted, were executed ‘in a continental style of painting’ (Foskett, 671). Walter Armstrong noted that Ward was ‘better known, however, by his engraved portraits, which show considerable skill’ (DNB). Examples of his mezzotint engravings are in the National Portrait Gallery's collection. George Ward died on 18 December 1878.

Early painting career

Ward's painting career is traditionally divided into two phases, the first dominated by the influence of George Morland, his brother-in-law, the second by Peter Paul Rubens, the great seventeenth-century Flemish master. However, such a division oversimplifies Ward's artistic development. When the young Ward began painting about 1790 both his subject matter and painting style were indebted to Morland. An early work such as Old Grey Horse and Ass (c.1791–3; V&A) demonstrates, in both its rustic subject matter and its style with loose brushwork, soft forms, and limited palette, how strong this influence was. Ward resented being labelled a student of Morland since he claimed that his brother-in-law, fearing competition, had taught him nothing. His so-called Rubensian phase was ushered in by his seeing in 1803 Rubens's Château de Steen (National Gallery, London). The picture had recently been acquired by the connoisseur Sir George Beaumont, and was in the studio of Ward's neighbour in Newman Street, Benjamin West, president of the Royal Academy. In response to this work Ward painted Bulls Fighting with a View of St Donat's Castle in the Background (1803; V&A).

There is no doubt that Ward was much influenced by the loosely painted rustic genre scenes of Morland and the richly colored baroque compositions of Rubens. However, the sources of Ward's mature style were numerous and diverse; they ranged from the Elgin marbles and other classical sculpture to old masters including Titian, Van Dyck, Paulus Potter, and Rembrandt as well as Rubens. He also studied animal and human anatomy and sketched constantly from nature. In the mid-1790s Ward had access to the Orléans collection that had come to England from revolutionary France to be sold; he engraved a number of the works for the art dealer Michael Bryan. Ward subsequently painted Bryan's family group portrait (c.1797–8; Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne), which shows the impact of Titian's palette on his early style. He was also familiar with the work of his British predecessors and contemporaries such as George Stubbs and P. J. de Loutherbourg, and occasionally looked to them for compositional and technical ideas. Ward's animal portraits are particularly indebted to Stubbs's compositions in which a horse or a dog is silhouetted against an expansive landscape, while a heightening of his colour reveals an admiration for the dramatic intensity of de Loutherbourg's palette.

At the turn of the century Ward created a series of paintings for the board of agriculture which set out to record the various breeds of livestock in Britain; the compositions were then engraved by Boydell. This undertaking clearly had nationalistic overtones during a period of ongoing hostilities with France. Championed by Lord Somerville, one of Ward's earliest patrons, the project was never completed. The paintings, for example A Durham Bull (c.1802; Nottingham Castle Museum), often incorporated landscape vignettes that are reminiscent of the compositions of Thomas Bewick, and their composition, fluidity of brushwork, rich coloration, and meticulous rendering of detail suggest Ward's many sources. Tireless in his efforts to gather information on British livestock, Ward travelled extensively throughout England. In the process he executed a large body of drawings that he utilized throughout his long life.

Ward hoped to establish his reputation with Bulls Fighting and Liboya Serpent Seizing its Prey (lost). The latter, painted on a monumental scale, depicted a serpent wrapping itself around an African seated on a white horse. Both these paintings may have had allegorical meanings with the former perhaps alluding to the current struggle between France and England and the latter to the evils of the slave trade. Ward was sympathetic to the anti-slavery movement and counted among his associates some of its leaders. Bulls Fighting is one of the earliest examples of Ward's use of parallel emotions in humans and animals, a common artistic conceit of the time, to underscore the drama taking place. Instead of gaining the approval of the artistic establishment, Bulls Fighting and Liboya Serpent brought on a temporary rupture with the Royal Academy. In part owing to its size, Liboya Serpent was rejected for exhibition and Bulls Fighting was relegated to an undesirable position. In a pique, Ward requested that he be allowed to withdraw the latter, and his petition was reluctantly granted. The rift was soon healed, however, as Ward recognized the importance of the academy to his professional future, and successfully sought amends through the diarist and painter Joseph Farington, as well as through other academicians. Ward was elected an associate of the Royal Academy in 1807, and was made a full academician in 1811. By this time he had established himself as an animal painter of the first order and his accomplishments could not be ignored by the art establishment, although some of his fellow artists found him vulgar.

Middle period

Ward's portrait of a celebrated stallion, Eagle (1809; Yale U. CBA) was critical in establishing his reputation. The Sporting Magazine's opinion was that the painting established Ward as ‘the first of English animal painters now living’ (1811, 265). Eagle exudes the power and force typical of Ward's finest animal portraits and with its anatomical detail and rich colouring also reveals some of the influences that shaped Ward's mature style. Shown in profile, the horse dominates a vast Rubensian landscape that seems to stretch to infinity beneath a brilliant Venetian-coloured sky.

Works such as Eagle brought Ward numerous patrons from the merchant class, landed gentry, and aristocracy. His one surviving account book, now on deposit at the Royal Academy, covers the period 1804 to 1827, when Ward became one of Britain's greatest animal painters. The majority of the commissions were for horse portraits, but the book also details paintings of other animals as well as landscapes and genre subjects. Ward also produced several major religious and history pictures at this time, such as The Waterloo Allegory, Pool of Bethesda, and Battle near Boston. The records of both the Royal Academy and the British Institution from these decades also suggest the artist's activity and ambition through the number of works exhibited and the subjects treated.

Despite receiving recognition as an outstanding animal painter Ward told Farington that he did not ‘wish to be admitted to the Academy as a Horse-Painter’, which he considered a lower form of art (Farington, Diary, 20 June 1811). The painting Ward submitted as his diploma piece, A Bacchanalian (1811; RA), underscores his aspirations. Although such works can be appreciated for their technical facility, they do not today occupy a high place in his œuvre nor were they generally admired at the time. On the other hand, Ward's animal paintings remain among the finest works he created and justify his being considered a major artist of the early nineteenth century.

Throughout the 1810s and 1820s Ward remained in great demand as a horse painter. Among the most important of his works are the portraits he made of horses in the early 1820s, especially those related to the combatants of the Napoleonic wars: Napoleon's charger Marengo (1824; priv. coll.); the duke of Wellington's Copenhagen (priv. coll.); and George IV's Nonpareil (Royal Collection). Although portraits of specific animals, the horses and landscapes also symbolized their owners. When exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1826, the landscape in the painting of Marengo (Napoleon's charger) was said to be emblematic of Napoleon's downfall. The setting sun and the horse's agitated appearance as it stares across a dark sea underscore the painting's message. When seen with Copenhagen (1824), it is clear that the two pictures were intended as companion pieces with Napoleon's steed looking to the right with fear across the channel at the horse of the duke of Wellington. Copenhagen is posed in a rolling English landscape, calm but wary, clearly prepared for what might happen. Nonpareil (1824) is placed in a landscape with Windsor in the background. The horse in proud majesty stands sentinel over its domain. These three portraits belong to a series of pictures of celebrated horses published as lithographs by Ackermann in 1823–4.

Gordale Scar and The Waterloo Allegory

In the two decades following his election as academician Ward produced some of his finest works. The subject matter varied enormously. In addition to animal paintings such as Eagle and portraits of men and animals hunting in a landscape, for example Theophilus Levett and a Favourite Hunter (1817; Yale U. CBA), Ward also attempted some of his most ambitious and monumental canvases, including Gordale Scar (1812–14; Tate collection), The Waterloo Allegory (1815–21), for which now only a large finished study exists (1815; Royal Hospital, Chelsea), and Group of Cattle (1822; Tate collection).

Commissioned by Lord Ribblesdale, whose son, Thomas Lister, studied with Ward, Gordale Scar depicts a dramatic site in Yorkshire. It is Ward's masterpiece. Guarded over by an aboriginal white bull and populated with a host of animals that could not fit within the topographical limitations of the actual scar, the dark and towering scene is a fine example of the sublime in British art. Other landscapes by Ward from the same period reflect the aesthetic ideas of the beautiful (Tabley Lake and Tower, 1814; Tate collection) and picturesque (A Cow-Layer: Evening after Rain, also called Cattle-Piece? Marylebone Park, 1807; Tate collection) that were also current at the time.

The Waterloo Allegory was commissioned by the British Institution after a competition to commemorate the victory of Wellington over Napoleon at Waterloo. Reportedly cut up when it was returned to Ward's descendants about 1880, it was a gigantic canvas that measured 21 × 35 feet. Its complex iconography, which includes a portrait of the duke of Wellington, representations of Britannia, and the visualizations of abstract concepts such as religion, charity, and envy, was adapted from a variety of sources, and the overall composition is indebted to Rubens's The Sacrament Triumphant over Ignorance and Blindness. The painting's apocalyptic imagery as well as the elaborate explanation reflect to some extent the ideas of the German mystic Jacob Böhme. Exhibited in London with an admission fee at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, The Waterloo Allegory was a failure, financially and critically. Angered by the response, Ward set out to prove his detractors wrong by painting Group of Cattle (1822; Tate collection), a life-size canvas conceived to compete with Paulus Potter's Young Bull (Mauritshuis, The Hague). This monumental painting (129½ × 191 inches) was purchased by the National Gallery in 1862; it has not been on view for decades. As in many of Ward's paintings, the animals take on an almost anthropomorphic quality, and in subsequent works such as The Deer-Stealer (1822; Tate collection), Day's Sport (1826; Yale U. CBA), and L'amour du cheval (1827; Tate collection), he explored even further than he had in the past parallel emotions between man and beast.

Retirement and death

When Ward was working on The Waterloo Allegory his wife and two of his children died. With personal tragedy and professional problems, the artist turned increasingly to religion for solace and subjects. However, he still sought and executed animal portraits. In the late 1820s and 1830s he travelled to Newmarket and other parts of East Anglia in search of commissions. Letters and notebooks dealing with these trips are in the Research Library at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. On 27 October 1827 Ward married Charlotte Fritche (b. before 1778), a family friend. Three years later the couple retired to Cheshunt, Hertfordshire.

Prior to the departure for Cheshunt, Ward sold at Christies many works from his studio and rented out his house in Newman Street. Now aged sixty, the artist was clearly putting his life in order. There were many reasons for the move from London, not least of which were his wife's preference for country life and financial problems involving his children. But Ward also had an apocalyptic view of the future, and he expressed these sentiments in letters to friends and in the treatise New Trial of the Spirits (1835), which was a defence of Edward Irving, whose Catholic Apostolic Church was near Ward's house in Newman Street. Convinced that he was one of the elect and with strong millenarian beliefs, Ward saw in contemporary events signs of the second coming and warnings about the approaching end of the world.

Ward considered painting his religious duty. Although he continued to portray animals and regularly sent works to exhibition, he became increasingly divorced from the art world and his non-commissioned works were often religious. Intercession (1837), which depicted Christ at the last few moments on the cross, was so criticized when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy that Ward was stung into response. The next year eight works, all somehow dealing with this slight, were exhibited. The most pertinent was Tickling the Ear (1838), in which a monkey (critic) sitting on the back of a bull (British public) tickles the animal's ear with a peacock feather (flattery). Ignorance, Envy and Jealousy, formerly Miranda and Caliban (1837; Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford upon Avon), dealt with the critic's calumny concerning Ward's religious beliefs; the iconography is indebted to Böhme.

Not infrequently Ward's exhibition pictures had lengthy explanations or poems, written by the artist, in the catalogue. He also wrote pamphlets that dealt with such things as cruelty to animals in the docking of a horse's tail and a defence of a beard (his was long and white). Even when, about 1840, he painted a series of pictures devoted to the life of the horse, the works had strong moralistic overtones. Although ostensibly about horses, these paintings were actually conceived as a means of exploring man's spiritual and moral state by comparing human and animal conditions, as is evident from the descriptions in the catalogue for the exhibition at Newman Street in 1841.

For the next twelve years Ward continued to exhibit regularly at both the Royal Academy and the British Institution. Although he still occasionally produced a significant work, both his technical and his mental powers were on the decline. His painting became increasingly mannered and his compositions could be awkward. The Council of Horses (exh. RA, 1848) was one of his last major works to sell to an important collector, Robert Vernon. At the time Ward's financial situation was so bad that he had petitioned the Royal Academy the previous year for a pension of £100 annually, and received the grant. He continued to paint, and two landscapes dealing with the cruelty of deer-hunting, exhibited at the academy in 1852, served as a coda to his long career. A few years later he suffered a stroke and his career was at an end. He died on 16 November 1859 at his home, Round Croft Cottage, Cheshunt, Hertfordshire, and was buried in Kensal Green, London. He was survived by his wife.

James Ward was considered by his contemporaries to be the greatest animal painter of his generation; however, his œuvre covered a wide range of subject matter from landscape to portraiture (human as well as animal), from genre to history painting (allegorical, religious, literary, and mythological subjects), and even an occasional still life. Extraordinarily prolific, Ward produced hundreds of paintings and thousands of drawings during his long life. But his output was also extremely uneven. His greatest works were executed in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. The large quantity and varying quality of his work make a balanced evaluation of him as an artist difficult. Nevertheless, he ranks among the leading artists of the British Romantic movement, particularly in his depiction of horses and in his rendering of dramatic landscapes. Examples of his work are held by many public collections, including the Tate collection, Victoria and Albert Museum, and National Portrait Gallery in London, the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, and the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut.

Edward J. Nygren DNB