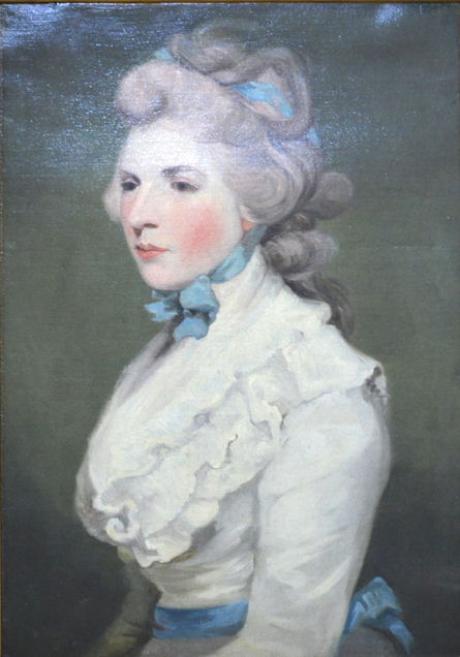

The date of the hairstyle and clothing looks to be about 1785-1790. The ornate hair styles of this decade incorporated ribbons and it was fashionable to wear a ribbon around the neck, sometimes with a brooch pinned to it. With thanks to Dr Susan North with her help in dating that clothing. The Original portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds is in the National Museum, Havana, Cuba.

Engraved by John Jones, after Sir Joshua Reynolds mezzotint, published 1784 (1783)

- Elizabeth Twiss2 d. 1858

- Horace Twiss+3 b. 28 Feb 1787, d. 4 May 1849

- unknown daughter Twiss2 b. c 1789, d. 1789

- Frances Ann Twiss2 b. 1790, d. 1864

- Amelia Twiss2 b. 1791, d. 1852

- Caroline Twiss3 b. c 1792, d. c 1 May 1808

- Edward Twiss3 b. 16 Mar 1795

- John Twiss2 b. 1798, d. 1866

Her Husband Francis Twiss (bap. 1759, d. 1827), concordance compiler, was born in Rotterdam, and baptized at the English Episcopal Church there on 5 April 1759, the sixth, and third surviving, of the eight children of Francis Twiss and his wife, Anne, née Hussey. The eldest child Richard Twiss (1747–1821) survived, but the next three died in infancy. Francis Twiss the father was an English merchant from Norwich and descended from Richard, the fourth son of Richard and Frances Twiss, who had gone to co. Kerry in Ireland about 1640, resided in the castle of Castle Island, and acquired possession of Killintierna (Burke, Gen. GB, 1871, 1424).

Of his early life it is known only that Twiss was admitted as a pensioner to the second table at Pembroke College, Cambridge, on 30 October 1776, under the college tutors Turner and George Pretyman, but evidently remained in residence for only one year. In the early 1780s he was evidently living mainly in the London area, and acquiring a reputation as a critic of Shakespearian acting. He became a friend of John Philip Kemble, and reputedly developed ‘a hopeless passion’ for Kemble's sister Sarah Siddons, sufficient to draw him to Belfast to watch her performances there in 1785 (Kemble, 1.21; Parsons, 151–2, 98). He also befriended Elizabeth Inchbald, reading with her and criticizing her plays (Manvell, 33–4, 48); she described him as one ‘whose integrity nothing could warp’ (Parsons, 151).

Sarah Siddons was doing all she could to promote the theatrical careers of her sisters and brothers. Her sister Frances Kemble (1759–1822) appeared on stage in Bath and Bristol in 1780–81, and in London first on 6 January 1783, but critics began to find her diffidence and lack of dramatic power irritating; and the compiler of ‘Theatrical intelligence’ for the Public Advertiser became obsessively harsh about her, often reducing her to bitter weeping. To her defence came the Shakespearian commentator George Steevens, with a letter of protest published in that paper (Boaden, Siddons, 2.20–26), and other expressions of support and admiration. He proposed marriage, but she and her family found him ‘too vehement and impracticable a suitor, too ill-tempered and capricious’ (Fitzgerald, 230), and instead, on 1 May 1786, in the church of St Giles-in-the-Fields, London, Fanny married by licence Francis Twiss. Sarah wrote of him as ‘a most respectable man, though of but small fortune, and I thank God that she is off the stage’ (letter to the Revd Thomas Whalley, 11 Aug 1786, cited in Parsons, 152). Their offspring were Horace Twiss (1787–1849), a daughter who died in infancy in 1789, Frances Ann (1790–1864), Amelia (1791–1852), Elizabeth (d. 1858), and John (1798–1866).

The Twiss family evidently remained in London until about the turn of the century, but by 1802 were resident in Bath. Sarah remained deeply attached to her sister. Mrs Hester Piozzi in a letter to Mrs Pennington of 29 April 1798 wrote that when visiting Sarah's house, ‘I always meet Mr. Twiss there—a fierce Man … with a Brown Brutus Head [a fashionable wig]’. Later references were more appreciative, for example, on 21 December 1802, to ‘that wise Man Mr. Twiss, with his clear straightforward Understanding’ (Piozzi Letters, 2.491; 3.391). During this period they bore some of the brunt of the painter Thomas Lawrence's troublesome courtship of Sarah's daughter Sally.

Twiss's A Complete Verbal Index to the Plays of Shakespeare, Adapted to All the Editions, was published in two volumes in 1805, but of the 750 copies printed 547 were reportedly destroyed in a fire in 1807. The value of Twiss's Complete Verbal Index to ‘all Shakespearians’ was rated very highly by James Boaden in 1827. Manifestly its compilation was ‘a task of the most irksome toil’, demanding ‘persevering diligence’ (Boaden, Siddons, 2.102n). Doubtless it would have been for several decades more accessible, and more extensive in its references, than that of Samuel Ayscough (1790). However, its usefulness was limited, as it printed the word only, and not the line or clause in which this occurred, and it was superseded by later concordances.

In 1807, Mrs Twiss established a private school for girls in Bath, at 24 Camden Place, with the assistance of her husband and daughters. In 1803 her father Roger Kemble had bequeathed her £500, to be paid at the death of her mother, which occurred on 24 April 1807; and this doubtless financed the venture. ‘A fashionable parlour-boarders' school’, it was quite successful, its prospectus promising that ‘The utmost attention will be paid to [the girls'] morals, conduct and manners’. The fees were relatively high, at ‘100 quineas per annum’, with ‘Entrance five guineas’ (Fitzgerald, 1.231).

Frances Anne Kemble (1809–1893), their niece, recalled her uncle as a ‘grim-visaged, gaunt-figured, kind-hearted gentleman and profound scholar’ (Record of a Girlhood, 1.21). George Hardinge described him as:

of my height, but very thin, and stoops. His face is ghastly in the paleness of it. He takes absolute clouds of snuff, and his eyes have an ill-natured cast of acuteness in them. He is a kind of thin Dr. Johnson without his hard words (though he is often quaint in his phrase); very dogmatical, and spoilt as an original. (Nichols, 3.38)

Mrs Frances Twiss died on 3 October 1822 in Bath, and Francis Twiss died on 28 April 1827 in Cheltenham. Their elder son, Horace Twiss, became a socialite, barrister, and member of parliament. The younger son rose to the rank of major-general in the army, on 5 January 1864, and became governor of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. Their three daughters remained unmarried.

John C. Ross DNB

Reynolds, Sir Joshua (1723–1792), portrait and history painter and art theorist, was born on 16 July 1723 at Plympton, Devon, the seventh of the eleven children of Samuel Reynolds (1681–1745), schoolmaster, and his wife, Theophila Potter (1688–1756) of Great Torrington, Devon. Reynolds's maternal grandfather was Humphrey Potter, rector of Nymet Rowland and curate-in-charge of Lostwithiel, his great-grandfather being the eminent mathematician the Revd Thomas Baker. Samuel Reynolds's family also numbered several prominent clergymen. His father, John, had been vicar of St Thomas's, Exeter, and prebendary of Exeter. His uncle, also John, was a fellow of King's College, Cambridge, and Eton College, while another uncle, Joshua, was a fellow and bursar of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and rector of Stoke Charity, Hampshire. The young Joshua Reynolds was probably named after this uncle. Yet in the baptismal register of Plympton St Maurice, Reynolds's name was entered on 30 July 1723 as ‘Joseph son of Samul Reynolds Clerk’, the entry being amended only after his death. This may have been a simple clerical error, or perhaps Samuel Reynolds had a change of heart and renamed his seventh child.

Education and apprenticeship, 1723–1743

On 9 December 1711 Samuel Reynolds, a former scholar of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, had married at Monksleigh, near Torrington, Devon, having given up his fellowship at Balliol College, Oxford, earlier that year. Four years later, at the age of thirty-four, he was appointed master of the free grammar school, Plympton. It was here that Joshua Reynolds was educated by his father. Classes were small and the curriculum, in line with more advanced Lockean precepts, would have extended beyond the parameters of classical scholarship, to include geography, arithmetic, and drawing. In addition to his teaching Reynolds's father maintained regular correspondence with friends on topics ranging from medicine to metaphysics. He observed the stars through his telescope, cast horoscopes, and wrote treatises on subjects as diverse as theology and gout. Reynolds, too, conversed with his father's friends, notably the Revd Zachariah Mudge, whom Edmund Burke later described as ‘very learned & thinking & much inclined to Philosophy in the spirit of the Platonists’ (Hilles, Literary Career, 7). In addition to formal lessons, the young Reynolds was encouraged to read independently. Into his commonplace book (MS, Yale University) he copied passages from classical authors: Theophrastus, Plutarch, Seneca, Marcus Antonius, and Ovid, as well as Shakespeare, Milton, Pope, Dryden, Addison, Steele, and Aphra Behn. Significantly, the commonplace book also includes extracts from the writings on art theory by Leonardo da Vinci, Charles Alphonse Du Fresnoy, and André Félibien. The most influential text studied by Reynolds, however, was Jonathan Richardson's An Essay on the Theory of Painting of 1715. Lost for nearly 200 years, Reynolds's own annotated copy of Richardson's Essay turned up in a Cambridge bookshop, bearing the signature ‘J. Reynolds Pictor’ (G. Watson, ‘Joshua Reynolds's copy of Richardson’, Review of English Studies, 14, 1991, 9–12).

Reynolds's parents encouraged all their children to take a practical interest in art, his elder sister, Elizabeth, recalling how they had been allowed to draw on the whitewashed walls of a long passage with burnt sticks. As James Boswell later noted, Reynolds's ‘two eldest sisters did little things … and he copied them. He used to copy all the frontispieces and plates in books’ (Hilles, Portraits, 20–21). Several of these copies have survived (J. Edgcumbe, ‘Reynolds's earliest drawings’, Burlington Magazine, 129, 1987, 724–6). They include a slight perspective drawing from The Practice of Perspective by Jean Dubreuil, a detail of a library from William Parson's English translation of Félibien, The Tent of Darius Explain'd, and a figure adapted from Jacob Cats's Spiegel of 1656.

Reynolds's first recorded portrait, made at the age of twelve, dates from 1735. The subject was a local clergyman named Thomas Smart, tutor to Reynolds's boyhood friend Richard Edgcumbe. The painting, apparently made at the behest of Lord Edgcumbe, was executed in a boathouse using shipwright's paint and a piece of sailcloth. In 1738, when Reynolds was fourteen, his father entered into correspondence with a neighbouring landowner, James Bulteel, concerning his son's career prospects. Bulteel suggested that Joshua should go to London, offering to introduce him personally to ‘those in artistic circles’ (Hudson, 14). It was also suggested that Reynolds might train under his father as an apothecary, Reynolds himself declaring that he would rather be an apothecary than ‘an ordinary painter’ (ibid., 15). However, in the spring of 1740 it was agreed that Reynolds should be bound to the Devonian artist Thomas Hudson for a period of four years, rather than a full seven-year term as stipulated by the artists' guild, the Painter–Stainers' Company.

Hudson lived and worked in Newman's Row, Lincoln's Inn Fields, London, although he still spent a good deal of time catering to his native west country clientele. Reynolds's daily routine at this time involved running errands, preparing canvases, painting accessories in portraits, and perhaps even making replicas of Hudson's pictures. He also made drawings from casts of antique statuary, including one of the Laocoön. Even so, in later life Reynolds regretted that he had not received a proper academic training, lacking ‘the facility of drawing the naked figure, which an artist ought to have’ (Works, 1.xlix). In 1821 over fifty of his academic studies from both the male and the female figure were sold at auction. In terms of sheer numbers alone these drawings suggest that Reynolds had been in the habit of drawing from the living model, probably at the St Martin's Lane Academy.

In Hudson's studio Reynolds also made copies after pen-and-ink drawings by Guercino. They are uniformly of a very high quality, and Hudson retained several of them among his own old-master drawings collection. Reynolds's knowledge of old-master paintings also developed during this time, principally through attending auctions, Hudson being in the habit of allowing him to bid on his behalf. It was at one such auction, at the sale of the earl of Oxford in March 1742, that Reynolds managed covertly to shake the hand of one of his boyhood heroes, Alexander Pope.

Early career, 1743–1749

Reynolds's apprenticeship with Hudson ended abruptly in the summer of 1743, occasioned apparently by a minor disagreement over Reynolds's refusal to carry out an errand. The quarrel was quickly patched up, and their relationship resumed on a more equal footing. By December 1744 Samuel Reynolds reported that ‘Joshua by his master's means is introduced into a club composed of the most famous men in their profession’ (Leslie and Taylor, 1.28). This club, composed of artists and connoisseurs with a common interest in old-master prints and drawings, probably met at Old Slaughter's Coffee House in St Martin's Lane, which the contemporary engraver and diarist George Vertue described as ‘a rendezvous of persons of all languages and nations, Gentry, artists and others’ (Vertue, Note books, 3.91).

By the autumn of 1743 Reynolds was dividing his portrait practice between London and Plymouth Dock. He made the most of the opportunities presented, his father reporting in January 1744 that he ‘has drawn twenty already, and has ten more bespoke’ (Cotton, Works, 58). In order to expedite the process, he briefly went into partnership with an unnamed artist who painted the bodies while Reynolds concentrated on the heads. On one occasion this resulted in the inadvertent production of a portrait of a man with two hats, one on his head and the other tucked under his arm (Whitley, 1.104). It was during this time, according to Reynolds, that he ‘became very careless about his profession, and lived … in a great deal of dissipation with but indifferent company’ (J. Prior, Life of Edmond Malone, 1860, 404–5). The few surviving portraits of this period, notably those of the Kendall family (Mannings, Reynolds, 1285–6), indicate that Reynolds was then working very much in the manner of Hudson, turning out competent, if unexceptional, works.

Reynolds's burgeoning talent emerges more clearly in the portraits of his immediate family, painted about 1745–6, notably those of his sister Frances (known as Fanny) Reynolds, his father (City Museum and Art Gallery, Plymouth), and his own self-portrait (priv. coll.). The principal pictorial influence on all three portraits is Rembrandt, the artist who was to influence Reynolds more profoundly than any other, especially in his earlier career. During this period Reynolds also painted a number of self-portraits in the manner of Rembrandt, of which the most celebrated (c.1749; NPG) shows him peering out towards the viewer, shading his eyes with his hand.

After his father's death on Christmas day 1745 Reynolds's mother, Theophila, vacated the schoolhouse at Plympton and moved to Torrington, where she lived with her eldest daughter, Mary, until her own death in 1756. Reynolds, meanwhile, took a house in Plymouth Dock with two of his unmarried sisters, Fanny and Jane. Although he was active in London, his principal patrons were from the west country, notably Richard Eliot, MP for St Germans and Liskeard and auditor and receiver-general to Frederick, prince of Wales, in Cornwall. In addition to his various portraits of members of the Eliot family, Reynolds painted their friend Captain John Hamilton (priv. coll.). When he saw this portrait many years later, Reynolds was ‘surprised to find it so well done; and comparing it with his later works, with that modesty which always accompanies genius, lamented that in such a series of years he should not have made a greater progress in his art’ (Malone, 1.xi).

By 1747 Reynolds was spending extended periods in London, now maintaining a studio in apartments on the west side of St Martin's Lane. Little is known about his personal life at that time, although he appears to have been romantically attached to a Miss Weston of Great Queen Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields, who may have been related to Bishop Stephen Weston of Exeter. The tone and content of the letters he wrote to her on his way to Italy (including one signed ‘From your slave’) indicate that they were on intimate terms. Other friends included the painters Robert and Simon Pine and John Wilkes, the radical. In November 1748 the Universal Magazine included Reynolds's name in a list of fifty-seven ‘Painters of our own nation now living, many of whom have distinguished themselves by their performances, and who are justly deemed eminent masters’. Of those named only Thomas Gainsborough was younger. In 1748 Reynolds was also commissioned by the corporation of Plympton to paint portraits of Lieutenant Paul Henry Ourry (Saltram, Devon) and Commodore George Edgcumbe (NMM), younger brother of Reynolds's boyhood friend Richard Edgcumbe. Through Edgcumbe, Reynolds became acquainted with Augustus Keppel, a younger son of the second earl of Albemarle, who on 26 April 1749 made an unscheduled stop at Plymouth on board the Centurion. Two weeks later, on 11 May, Reynolds set sail with Keppel for the Mediterranean.

Italy and France, 1749–1752

Reynolds travelled with Keppel from Plymouth to Minorca, with brief stops at Lisbon, Cadiz, and Gibraltar, and a detour to Morocco in order to secure the release of the imprisoned British consul. Reynolds had a pleasant journey, taking wine with Keppel in his cabin, reading his books, and observing a bull-fight in Spain. They arrived at Port Mahón on 18 August 1749. Here Reynolds suffered a riding accident in which he sustained injuries to his face, telling Miss Weston that his lips were ‘spo[iled now for] kissing’ (Letters, 7). Reynolds was compelled to remain on Minorca for longer than he had planned, although it gave him the opportunity to paint portraits of the British garrison stationed there, and earned him upwards of £100. Many years later an old soldier recalled to Fanny Burney: ‘He drew my picture there, and then he knew how to take a moderate price; but now I vow, ma'am, 'tis scandalous—scandalous indeed! To pay a fellow here seventy guineas for scratching out a head!’ (The Early Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney, ed. L. Troide, 1994, 3.414).

In January 1750 Reynolds left Port Mahón for Italy, and by Easter was in Rome. There he set about making copies of old-master paintings. They included a small copy of Raphael's School of Athens and a full-scale copy of Guido Reni's St Michael, which Reynolds recorded having made in Santa Maria della Concezione between 30 May and 10 June, and which his niece later presented to George IV. Reynolds spent many hours in the Vatican scrutinizing the work of Michelangelo and Raphael's frescoes in the Stanze. As he later recalled:

I found myself in the midst of works executed upon principles with which I was unacquainted: I felt my ignorance and stood abashed. Notwithstanding my disappointment, I proceeded to copy some of those excellent works. I viewed them again and again; I even affected to admire them, more than I really did. (Works, 1.xvi)

He also made a thorough inspection of the city's myriad churches and religious foundations, and the spacious private palaces owned by patrician families such as the Colonna, Borghese, and Barberini. His impressions, in the form of both sketches and written description, were recorded in notebooks (MSS, department of prints and drawings, BM; Sir John Soane's Museum, London; Harvard U., Fogg Art Museum; Metropolitan Museum, New York; Beinecke Library, Yale University; priv. coll.). Collectively the notebooks reveal that while Reynolds respected the high Renaissance he was instinctively drawn to the art of the later sixteenth century and seventeenth century, including a number of lesser-known artists such as Federico Barocci, Andrea Sacchi, and Sacchi's pupil Carlo Maratta.

Reynolds was a diligent student. He also had a keen sense of humour, as the series of caricatures he produced during his time in Rome reveal. Of these, the most ambitious was an inventive parody of Raphael's School of Athens (NG Ire.), depicting a rabble of assorted ‘milordi’, tutors, painters, and picture dealers, many of whom were close personal friends. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Reynolds did not undergo any sort of formal training in Italy. However, he formed friendships with a number of continental artists, including the young French decorative painter Gabriel-François Doyen, with whom he swore a vow of friendship before the statue of Marcus Aurelius, and Claude-Joseph Vernet, then among the most popular painters of Roman landscapes and seascapes. He also met an Italian youth, Giuseppe Marchi, who returned with him to England, becoming his pupil and lifelong factotum.

Reynolds left Rome on 5 April 1752. Following a brief visit to Naples he set out for Florence on 3 May, accompanied by the artists John Astley and Samuel Hone. They travelled via Assisi, Perugia, and Arezzo. In Florence the sculptor Joseph Wilton, whom he had known in Rome and whose portrait he now painted (NPG), acted as Reynolds's guide. Reynolds made a careful study of works in the Pitti Palace, including Raphael's Madonna della sedia, Titian's Mary Magdalen (‘an immense deal of hair, but painted to the utmost perfection’; Reynolds, ‘Notebooks’, BM, LB 12, fol. 29v), and two large paintings of Henry IV by Rubens (now in the Uffizi gallery, Florence). His predilection for mannerism surfaced once more in his enthusiastic comments on the art of Barocci and Matteo Rosselli and on the sculpture of Giambologna, whom he then rated as highly as Michelangelo.

On 4 July 1752 Reynolds left Florence for Bologna, where he expressed a particular admiration for Lodovico Carracci, an artist whom he was to regard with exaggerated respect throughout the rest of his life. After ten days in Bologna, Reynolds travelled to Venice via Modena, Parma, Mantua, and Ferrara, reaching Venice on 24 July 1752. There he spent time with the Italian painter Francesco Zuccarelli, analysing the technical methods of the great Venetian colourists Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese. He also found time to make sketches of paintings by Giambattista Tiepolo. Improbably, his greatest praise was reserved for a large crucifixion in the church of San Lio, by the minor baroque artist Pietro Muttoni della Vecchia (1605–1678), a work which he declared to be ‘equal to any masters whatsoever’ (Reynolds, ‘Notebooks’, BM, LB 13, fols. 78r and 48v).

Reynolds left Venice on 16 August 1752, and travelled to Padua, Milan, and Turin. Late in August, accompanied by Marchi, he crossed the Alps, where he had a chance encounter with his old master, Thomas Hudson, and the French sculptor François Roubiliac, who were on their way to Rome. Temporarily short of money, Reynolds journeyed alone to Paris by coach, Marchi following behind on foot. Reynolds arrived in Paris on 15 September, Marchi three days later (sketchbook, Metropolitan Museum, New York, fol. 178). In Paris Reynolds spent time with the architect William Chambers, whose fiancée he then painted (Kenwood House, London). He also looked at works by the old masters, including Van Dyck, Jordaens, Rubens, Rembrandt, and Titian. However, he concluded that the French ‘cannot boast above one painter of a truly just and correct taste’, Nicholas Poussin (Leslie and Taylor, 1.86–7). After a month Reynolds headed for Calais, where he was reunited with Hudson and Roubiliac. They crossed the channel to England together, Reynolds arriving in London with Marchi on 16 October. Reynolds did not return to Italy. However, he was to make two further visits to Paris in 1768 (9 September – 3 October) and 1771 (15 August to early September).

Appearance and character

Reynolds was about 5 feet 6 inches tall, with ruddy, rounded facial features. He was partially deaf, which caused him in later life to affect a large silver ear-trumpet. He blamed the affliction upon a chill caught in the Sistine Chapel, although it was probably hereditary, as was his slight harelip. ‘His pronunciation’, recalled a female acquaintance, ‘was tinctured with the accent of Devonshire; his features coarse, his outward appearance slovenly’ (C. Knight, Autobiography, ed. J. W. Kate, 1861, 1.9). Although he could, when occasion demanded, dress smartly, he preferred to assume a casual demeanour, taking snuff while he painted, and often spilling it down his waistcoat. Among friends, of whom he had many of both sexes, Reynolds was admired for his generosity, even temper, and capacity for listening. His dinner parties were notorious for their air of anarchic bonhomie, Reynolds invariably inviting far more guests than could be accommodated at his table. He was addicted to card games and was an incorrigible gambler. As a fellow artist observed: ‘If He went into a Company where there was a Pharo table, or any game of chance, He generally left behind him whatever money He had abt. him’ (Farington, Diary, 2.307). Yet in private Reynolds could be cynical and aloof, particularly towards his pupils and his younger sister, Fanny, who acted as his housekeeper during his middle years.

Early maturity, 1752–1760

Following a short reunion with family and friends in Devon, Reynolds resumed his portrait practice in London, initially in apartments at 104 St Martin's Lane and subsequently at a large house at 5 Great Newport Street (afterwards demolished), where his sister Fanny joined him as housekeeper. Among the first portraits he painted on his return one depicted Giuseppe Marchi (RA) in an exotic ‘oriental’ headdress and crimson coat, which he retained in his studio as an advertisement. He also made portraits of a number of prominent whig grandees, including the fourth duke of Devonshire, Lord Grafton, and the secretary of state, Lord Holdernesse. However, it was his full-length portrait of Augustus Keppel (NMM) that revealed the extent of his ambition. The figure's pose was modelled on a statue of Apollo by the seventeenth-century French sculptor Pierre Legros the younger, the treatment of light and colour being inspired by Tintoretto.

During the 1750s Reynolds began to experiment increasingly with his painting technique, employing an unusually wide range of pigments, oils, and varnishes. While these experiments often resulted in brilliantly coloured and highly textured works, the instability of certain pigments (notably red lake, carmine, and orpiment) and his incautious combining of incompatible materials resulted in fading and cracking. These shortcomings did not appear to concern Reynolds, who, when challenged, retorted, ‘all good pictures crack’ (Leslie and Taylor, 1.112–13). At this time Reynolds also began to tender out the painting of costume in his portraits to professional drapery painters, notably Peter Toms and George Roth, who also painted drapery for Hudson. By now Reynolds was extremely busy, producing over 100 portraits a year. And as he became more successful so his prices rose accordingly. In 1753 he charged 48 guineas for a full-length portrait; by 1759 the price had risen to 100 guineas, and by 1764 to 150 guineas (Cormack, 105). Reynolds often worked a seven-day week, save for a hiatus in the months of July and August, when his fashionable clientele deserted the city. From 1755 until he ceased painting in 1790 Reynolds noted appointments with his sitters in small diaries, or ‘pocket books’, of which most have survived (RA; Cottonian Library, Plymouth), and which provide detailed information on his working life and social engagements.

By the late 1750s Reynolds had established a systematic method of determining the attitudes chosen for portraits, keeping a portfolio of engravings after his own and other artists' works from which sitters could choose and adapt poses. The first mezzotint engraving after one of his paintings was Lady Charlotte Fitzwilliam, made by the Irishman James MacArdell, who before his death in 1765 engraved thirty-seven plates after Reynolds. Subsequent engravers included James Watson, John Dean, John Raphael Smith, Valentine Green, and his own pupils, Marchi and William Doughty. These engravings, as much as the paintings themselves, were responsible for promoting Reynolds's work at home and abroad, and were exhibited by engravers in their own right, occasionally even prior to Reynolds's original paintings. Reynolds, who did not charge engravers to copy his works, recognized the importance of prints, allegedly stating after MacArdell's death, ‘by this man I shall be immortalized’ (Waterhouse, 1973, 20).

By the mid-1760s Reynolds's painting style was emulated by a number of his contemporaries, notably Francis Cotes and Tilly Kettle. Reynolds's own relations with his fellow artists were generally cordial, although he seldom became close. An exception was the Scottish portraitist Allan Ramsay, who exerted a considerable influence over Reynolds's own work, and whom Reynolds befriended in 1757. As Horace Walpole memorably remarked, ‘Mr. Reynolds and Mr. Ramsay can scarce be rivals, their manners are so different. The former is bold, and has a kind of tempestuous colouring; yet with dignity and grace; the latter is all delicacy’. He added somewhat unfairly, ‘Mr. Reynolds seldom succeeds in women; Mr. Ramsay is formed to paint them’ (Walpole, Corr., 15.47). As his portrait of Georgiana, Countess Spencer, and her daughter reveals (1760–66; priv. coll.), Reynolds was capable of conveying the same air of intimacy and naturalism which pervades Ramsay's portraiture, although he possessed a directness to which Ramsay seldom aspired.

The middle period, 1760–1768

In the summer of 1760 Reynolds purchased a lease on a house at 47 Leicester Square, then among the most fashionable residential areas of the capital. (It was subsequently converted into auction rooms and demolished in 1937.) Reynolds remained there for the rest of his life. He marked his arrival with a grand ball, and set about completely refurbishing the property, adding a series of studios and a picture gallery to the rear of the premises where he displayed his paintings alongside his growing collection of old-master paintings. He also acquired a secondhand coach in which he encouraged his sister to ride, to her considerable embarrassment. Reynolds's studio was a small octagonal room, lit by a single window situated high above the ground. Portrait sitters occupied an upholstered armchair (now in the RA), revolving on castors and raised about 18 inches from the floor on a dais. Reynolds stood, observing his sitters at eye level, looking directly at them or at their reflection in a mirror. According to one sitter he would ‘walk away several feet, then take a long look at me and the picture as we stood side by side, then rush up to the portrait and dash at it in a kind of fury. I sometimes thought he would make a mistake and paint on me instead of the picture’ (W. P. Frith, My Autobiography and Reminiscences, 1888, 3.124).

In April 1760 Reynolds participated in the first annual exhibition of works held by the Society of Artists at the Society of Arts on the Strand. He exhibited five pictures including Elizabeth Gunning, Duchess of Hamilton and Argyll (Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight), the first in a long line of public female full-length portraits in the ‘grand manner’. Reynolds exhibited with the Society of Artists every year (except 1767) until 1768. Among the works he showed there were Laurence Sterne (1761; NPG), Garrick between Tragedy and Comedy (1762; priv. coll.), Nelly O'Brien (1763; Wallace Collection, London), Lady Sarah Bunbury (1765; Art Institute, Chicago), and Mrs Hale as ‘Euphrosyne’ (1766; priv. coll.). Of these Garrick between Tragedy and Comedy provides the clearest indication of Reynolds's ambition. On a formal level it displays Reynolds's knowledge of the tenets of Western post-Renaissance art theory, the figures of Comedy and Tragedy representing the choice to be made by the artist between the allure of colour and the strictures of line. It also reveals, through a parodic allusion to the classical theme of the Choice of Hercules, how Reynolds perceived that painting could aspire to the level of poetry and claim its rightful place among the liberal arts.

Like so many of Reynolds's paintings Garrick borrowed pictorial devices from a number of other artists (in this case Rubens, Guido Reni, and William Dobson). During his lifetime critics believed that these ‘borrowings’ indicated a lack of creativity. And it has since been suggested that Reynolds himself hoped that they would not be detected (E. Wind, ‘Borrowed attitudes in Reynolds and Hogarth’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 2, 1938–9, 182–5). Yet for Reynolds and his contemporaries, pictorial references to old-master paintings were visual counterparts to the Augustan literary cult of imitation. For Reynolds, as for Johnson, imitation was a ‘kind of middle composition between translation and original design, which pleases when the thoughts are unexpectedly applicable, and the parallels lucky’ (The Works of Samuel Johnson, ed. A. Murphy, 1792, 11.132). To Reynolds these borrowings constituted an intellectual and visual game, as he plundered his own sketchbooks, his portfolios of prints, and paintings in order to enrich the iconography of otherwise formulaic society portraits.

In 1759 Reynolds painted a portrait of George, prince of Wales (Royal Collection), presumably with the hope of securing further royal patronage. In the following year his hopes were dashed when the prime minister, Lord Bute, recommended Allan Ramsay to the post of principal painter to the king. From this moment there was increasing antipathy between Reynolds and the king. Professionally it did Reynolds no harm whatsoever for, as Johnson remarked, ‘it is no reflection on Mr. Reynolds not to be employed by them; but it will be a reflection on the Court not to have employed him’ (G. B. Hill, ed., Johnsonian Miscellanies, 1897, 2.401–2).

Johnson, whom Reynolds had met about 1756, was the single most important influence on Reynolds's life during the 1750s and 1760s. ‘For my own part I acknowledge the highest obligations to him. He may be said to have formed my mind and brushed off from it a great deal of rubbish’ (Hilles, Portraits, 66). Later, in August 1764, when Reynolds was struck with a serious illness, Johnson wrote to him, ‘if I should lose you, I should lose almost the only Man whom I call a Friend’ (Boswell, Life, 1.486). Reynolds painted Johnson on a number of occasions; the earliest (NPG) portrayed him, as Boswell recalled, ‘in the attitude of sitting in his easy chair in deep meditation’. Later, in a painting for the wealthy brewer Henry Thrale, Reynolds attempted to capture Johnson's short-sightedness, which resulted in the celebrated retort, ‘He may paint himself as deaf if he chuses … but I will not be blinking Sam’ (H. L. Piozzi, Anecdotes of the Late Samuel Johnson, LL.D, 1786, 248). In 1759 Johnson commissioned Reynolds to write three essays for The Idler, thus launching his literary career. The essays addressed the concepts of beauty, imitation, and nature, and prefigured arguments that were to underpin his Discourses on Art, begun some ten years later.

In the summer of 1762 Reynolds and Johnson made a six-week tour of the west country, which included visits to family and friends. Back in London, in February 1764, Reynolds formed a dining club for Johnson's immediate circle. The Literary Club, or the Club, as it became known, was originally restricted to nine members, including Reynolds, Johnson, Edmund Burke, and Oliver Goldsmith, who were then Reynolds's closest companions. Reynolds painted Goldsmith between 1766 and 1767, in a dignified profile (Knole, Kent), Reynolds's sister Fanny referring to it as ‘the most flattered picture she ever knew her brother to have painted’ (Northcote, Life, 1.326). At about the same time Reynolds also painted a half-length portrait of Burke (priv. coll.), and a double portrait of him in the role of private secretary to the earl of Rockingham (FM Cam.). The picture was never completed, possibly owing to the collapse of Rockingham's ministry in July 1766. Even so, it is of great value for the light it sheds on Reynolds's working practices, the slightly sketched outlines of the figures forming a marked contrast to the painstaking details of the Turkey rug and inkstand, produced by his pupils and drapery painters.

Aside from Marchi, Reynolds's first recorded pupil was Thomas Beach, who studied with him from about 1760 to 1762. Other pupils included John Berridge, Hugh Barron, William Parry, and, in the 1770s, James Northcote and William Doughty. These pupils were not formally indentured but exchanged their services in return for board, lodging, and, if they were lucky, a little ad hoc tuition. Reynolds's pupils remained surprisingly ignorant of his working methods and, as one remarked, he ‘never saw him unless he wanted to paint a hand or piece of drapery from them, and then they were dismissed as soon as he had done with them’ (Gwynn, 49). Of Reynolds's pupils, the most successful, if not the most gifted, was James Northcote, who studied under him from 1771 to 1776, and who was to be Reynolds's biographer. Northcote's admiration for Reynolds was tempered by jealousy, and an abiding resentment that he had not enjoyed the same intimacy as Reynolds reserved for his friends and patrons. He later recalled that if ‘Sir Joshua had come into the room where I was at work for him and had seen me hanging by the neck, it would not have troubled him’ (Leslie and Taylor, 2.601). Reynolds was generally kinder to those who did not work directly under him. He assisted the careers of several young foreign artists, notably the Americans Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley, whose Boy with a Squirrel (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), he exhibited next to his own work at the Society of Artists in 1766. Reynolds's greatest personal encouragement was reserved for the young Irish artist James Barry, who was introduced to him by their mutual friend Edmund Burke in 1764.

The Royal Academy and the Discourses on Art

In the years immediately following his return from Italy Reynolds took a keen interest in plans by the St Martin's Lane Academy and the Society of Dilettanti to form a Royal Academy [see Founders of the Royal Academy of Arts]. During the early 1760s he was intimately involved in the planning of exhibitions by the Society of Artists. However, in 1765 he quite deliberately distanced himself from the internal politics of the society owing to the growing rivalry between the committee and its members. Reynolds's name is a notable omission from the twenty-two signatories to the memorial presented to George III on 28 November 1768, requesting his ‘gracious assistance, patronage, and protection’ in founding a Royal Academy. And it was only after some considerable hesitation, involving private consultation with Burke and Johnson, that on 14 December 1768 Reynolds agreed to accept the presidency of the Royal Academy. In the following year, on 21 April, the king knighted Reynolds at St James's Palace. On that day Johnson broke his vow of abstinence and ‘drank one glass of wine to the health of Sir Joshua Reynolds’ (Hudson, 93).

Reynolds was intimately involved in the day-to-day running of the Royal Academy, rarely missing council or general assembly meetings. Occasionally he entertained his fellow academicians at home, treating the members of the council on one occasion to a supper of turtle (‘callipash and callipee’ (The Letters of Henry Fuseli, ed. D. Weinglass, 1982, 12). In 1771 Reynolds inaugurated the annual Royal Academy dinner in order to strengthen the link between the academy and connoisseurs. It was held annually on 23 April, the feast of St George, and continues to this day. In 1775, in an attempt to confer increased formality upon the academy, Reynolds proposed the introduction of ceremonial gowns for members. The idea was rejected, principally because of opposition voiced by the academy's treasurer William Chambers, who was from this time increasingly antagonistic towards Reynolds. Chambers features with Reynolds and Joseph Wilton, keeper of the Royal Academy, in an official portrait of 1782 by John Francis Rigaud (NPG).

Reynolds's greatest critic within the Royal Academy was James Barry, who in 1782 was elected as its professor of painting. Barry's differences with Reynolds were primarily ideological. Even so, he used his position and his annual academy lectures to mount increasingly personal attacks on Reynolds, who was apparently reduced ‘to so awkward a situation in his chair as an auditor, that he was obliged at last either to appear to be asleep or to absent himself from the place’ (Northcote, Life, 2.146). Although Reynolds affected indifference, he confessed privately that ‘he feared he did hate Barry, and if so, he had much excuse, if excuse be possible’ (ibid., 2.196).

The Royal Academy opened on 2 January 1769. To mark the occasion Reynolds read out an address, published the following month as A Discourse, Delivered at the Opening of the Royal Academy. Reynolds wrote fifteen discourses between 1769 and 1790, each one (with the exception of the inaugural Discourse and the ninth) delivered on the occasion of the distribution of prizes to the academy's students. From 1769 to 1772 they were delivered annually, thereafter biennially. Each discourse was published shortly after its delivery, Reynolds presenting a copy to each member of the academy, and each member of the Club. The first seven discourses were published together in 1778, and were subsequently made available in Italian and German editions. A French edition of thirteen appeared in 1787. The first collected edition of all fifteen, together with Reynolds's other writings, appeared in 1797. A second edition appeared in 1798: William Blake's extensively annotated copy belongs to the British Library. Over thirty other editions of the Discourses have since been published, including those by Sir Edmund Gosse (1884), Roger Fry (1905), and more recently by Robert Wark (1975) and Pat Rogers (1992).

One principal difference between the essays in The Idler and the Discourses was that the latter were addressed to a live audience prior to publication. Even in their published form, the Discourses adopt a very personal approach. Even so, Reynolds's measured prose masks the uncertainty of his spoken delivery. He had an undemonstrative speaking voice and the majority of those attending his lectures at the Royal Academy would not have been able to hear what he was saying (Hilles, Literary Career, 33–4). Reynolds organized his ideas, as well as the transcriptions taken from various reading materials, in folders with themed headings, including ‘Method of study’, ‘Colouring’, and ‘Michael Angelo’. In the weeks leading up to the presentation of each discourse Reynolds made copious notes and rough drafts, working late into the night to give form to his thoughts. At the last minute pupils were inducted as scribes, working against the clock to provide a fair copy to be read out at the academy, James Northcote telling his brother, ‘I writ out sir Joshua's discourse and he left it till the last day that he was to speak it in the evening so that if Gill had not assisted me it could not have been done soon enough’ (Whitley, 2.293). Reynolds also received editorial assistance from friends, notably Samuel Johnson, Edmund Burke, and, latterly, Edmond Malone. Even so, envious contemporaries who underrated Reynolds's abilities as a writer (Hilles, Literary Career, 134–40, 217–48) unjustly exaggerated their respective contributions.

In his first discourse Reynolds stressed the vital role played by the living model, a linchpin of academic training since the Renaissance. Subsequent discourses went beyond the scope of art education, synthesizing ideas found in a wide range of aesthetic treatises including classical authors, Horace and Longinus; Renaissance artists, Leonardo da Vinci and Lomazzo; French seventeenth-century theorists, Charles Le Brun, Henri Testelin, André Félibien, and Roger de Piles, as well as more recent texts by Algarotti, Winckelmann, Edmund Burke, and Adam Smith. In the earlier discourses, particularly the third and fourth, Reynolds set out his ideas on the guiding principles of high art, which he believed were embodied in the ‘great style’. According to Reynolds, the ‘great style’ endowed a work with ‘intellectual dignity’ that ‘ennobles the painter's art; that lays the line between himself and the mere mechanick; and produces those great effects in an instant, which eloquence and poetry, by slow and repeated efforts, are scarcely able to attain’ (Reynolds, Discourses, ed. Wark, 43). Reynolds was in no doubt that the artists who had come closest to this ideal were the Roman, Florentine, and Bolognese masters of the Italian Renaissance, especially Michelangelo, Raphael, and Lodovico Carracci. While he greatly admired the Venetians Titian and Tintoretto, Reynolds considered that their preoccupation with colour and effect militated against the purity and severity of the ‘great style’. In his later discourses Reynolds addressed major aesthetic concepts, including the nature of genius, originality, imitation, and taste. Here, again, he explored his themes with reference to the leading masters of the ‘great style’, although he appears increasingly to acknowledge the contributions of artists lower down the scale, such as Rubens and Rembrandt—both of whom greatly influenced his own art. As it has been argued (Reynolds, Discourses, ed. Wark, xxx–xxxii; ed. Rogers, 21–2), Reynolds's Discourses do not, with the passage of the years, incline him more towards a more ‘Romantic’ viewpoint, but retain an essentially empirical outlook that would have satisfied earlier generations. Yet while the Discourses collectively represent Reynolds's views on art theory and practice, they do not form a seamless, or even consistent, argument. Over the twenty-year period in which they were written events and experience modified his views. At times he wished to address specific issues: in the tenth discourse sculpture, in the fourteenth the art of Thomas Gainsborough. He also allowed different facets of his own intellectual make-up to surface, tempering his insistence on the primacy of rules with a willingness to countenance arguments based on custom, emotion, or gut instinct.

The 1770s

Between 1769 and 1779 Reynolds exhibited over 100 pictures at the Royal Academy, considerably more than he had exhibited during the previous decade at the Society of Artists. These included portraits of close friends, actors and actresses, scientists, clergymen, aristocrats, and children, as well as subject pictures and character studies. Among his friends he showed portraits of Johnson and Goldsmith (1770), Giuseppe Baretti (1774), and David Garrick (1776). John Frederick Sackville, third duke of Dorset, who assembled an entire room of Reynolds's paintings at Knole, purchased all these portraits, excepting that of Baretti (who at the time had been indicted for murder). Lord Sackville also purchased Reynolds's first major history painting, Ugolino and his Children in the Dungeon, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1773. Ugolino was based on an episode from Dante's Divina commedia. Reynolds regarded this picture as a manifesto for his theories on high art, combining within it motifs from Carracci's Pietà (National Gallery, London) and Michelangelo's Sistine ceiling, as well as theories derived from Richardson and Le Brun.

Although history painting formed a relatively small part of Reynolds's artistic output, he devoted increasing time to it from the early 1770s onwards. His acolytes, moreover, promoted Reynolds's history paintings as testimony to his genuine commitment to the cause of high art. In the decades following his death they were even counted among his greatest achievements, fetching great prices at auction and forming the focus of critical attention. Unlike his commissioned portraits, which he dispatched with due efficiency, Reynolds's history pictures are known to have taken months, even years, to complete. During the summer, when his portrait business was slack, Reynolds employed a variety of models, using them to explore his ideas on high art and to test out new painting techniques. In the early 1770s he employed an old beggar named George White who, as well as modelling the figure of Ugolino, sat to Reynolds as a pope, an apostle, and as a captain of banditti. He also painted beggar children. Indeed, more successful than Reynolds's history paintings were his character studies of children, known as ‘fancy pictures’. They included a Strawberry Girl (Wallace Collection, London), the Infant Samuel (Tate collection), and the pendant pictures Cupid as a Link Boy (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York) and Mercury as a Cut Purse (Farington Collection Trust, Buscot Manor, Oxfordshire. These last two were not exhibited in public, possibly because of the sexual innuendo they contained. Fancy pictures played an increasingly important role in Reynolds's oeuvre in the 1770s and 1780s, allowing him to paint more freely in the manner of old masters such as Murillo, Rembrandt, and Correggio, and to experiment with his technique. According to his pupil James Northcote, when Reynolds:

was at any time accused of having spoiled many of his portraits, by trying experiments upon them, he answered that it was always his wish to have made these experiments on his fancy pictures, and if so, had they failed of success, the injury would have fallen only on himself, as he should have kept them on his hands. (Northcote, Memoirs, lxxxi)

Reynolds also made imaginative ‘character’ portraits of women and children. Of these among the most successful are the pendants Master Crewe as Henry VIII (exh. RA, 1776; priv. coll.) and Miss Crewe as ‘Winter’ (1775; priv. coll.). At times Reynolds elided the two genres of fancy picture and portraiture, as in the portrait of his niece Theophila Palmer, which he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1771 as A Girl Reading (priv. coll.). She bitterly complained to him that she ought to have been described as ‘A Young Lady’. Reynolds retorted, ‘don't be vain, my dear, I only use your head as I would that of any beggar—as a good practice’ (Maria Edgeworth: Chosen Letters, ed. F. V. Barry, 1931, 380).

Aside from history painting and fancy pictures, among Reynolds's most ambitious works were the series of full-length female grand-manner portraits painted during the 1770s. They included The Duchess of Cumberland (exh. RA, 1773; priv. coll.), The Montgomery Sisters (exh. RA, 1774; Tate collection), The Countess of Harrington (exh. RA, 1775; priv. coll.), and Lady Bamfylde (exh. RA, 1777; Tate collection). In these portraits the subjects were dressed in voluminous robes which Reynolds hoped would endow them with a timeless quality and elevate the image towards the level of high art. Only occasionally did he resort to quasi-historical costume in male portraits, notably in the double portrait of Colonel John Acland and Lord Sydney (exh. RA, 1770; priv. coll.), portrayed in theatrical tunics as archers, and the Polynesian Omai (exh. RA, 1776; priv. coll.), whom he depicted in white robes and a turban—a form of dress apparently adopted by Omai during his sojourn in England.

Further honours were bestowed on Reynolds during the 1770s. In September 1772 he was elected an alderman of the borough of Plympton, and a year later, on 4 October 1773, he was sworn in as mayor. In 1775 Reynolds was elected a member of the academy at Florence, following the presentation of his self-portrait to the grand duke of Tuscany. The honour Reynolds undoubtedly valued most was the doctorate of civil law awarded him in July 1773 by the University of Oxford: in subsequent self-portraits (notably that painted for the Royal Academy in 1780) he often portrayed himself in his academic robes. In 1774 Reynolds also painted a portrait of his friend James Beattie in doctoral robes, Beattie having received his doctorate at the same ceremony as Reynolds. The portrait (Marischal College, Aberdeen), depicted Beattie holding his Essay on the Nature and Immutability of Truth in Opposition to Sophistry and Scepticism, while an avenging angel drives away his enemies, whom Reynolds characterized as David Hume and Voltaire. The painting was attacked by Goldsmith, who told Reynolds that while Beattie's book would soon be forgotten ‘your allegorical picture, and the fame of Voltaire will live for ever to your disgrace as a flatterer’ (Northcote, Life, 1.299).

By the late 1770s Reynolds's most influential patrons were invariably members of the country's leading whig dynasties. Between 1775 and 1778 he exhibited portraits of members of the Crewe, Bedford, and Spencer families, as well as George Townshend (Lord de Ferrars), Viscount Althorp, Lord Palmerston, the duke of Leinster, the duke and duchess of Devonshire, and the family of the duke of Marlborough. He made frequent visits to their country seats and entertained them in London. And although he continued to work hard during the day, evenings were increasingly given over to drinking, gaming, attending masquerades, and even dancing lessons. His pupil James Northcote recalled that ‘though the frequent dining-out probably shortened his life, it was of great advantage to him in his profession’ (Conversations of James Northcote R.A. with James Ward on Art and Artists, ed. E. Fletcher, 1901, 186). He belonged to several prestigious clubs including the Star-in-Garter in Pall Mall, Almacks, and the Society of Dilettanti, where he had been official ‘limner’ since 1769. Between 1777 and 1779 Reynolds painted two large group portraits of the members of the Society of Dilettanti, enjoying the communal pleasures of wine, conversation, and connoisseurship.

The deterioration of relations between Reynolds and his sister Fanny by the late 1770s resulted in her enforced departure from his house. Their niece Mary Palmer, who remained with Reynolds for the remainder of his life, assumed Fanny's duties as housekeeper. Unlike Fanny, whose artistic efforts Reynolds had belittled, Mary was encouraged to paint. Her own niece Theophila Gwatkin recalled: ‘Everybody in the house painted. Lady Thomond [Mary Palmer] & herself, the coachman & the man servant Ralph & his daughter, all painted, copied and talked about pictures’ (The Diary of Benjamin Robert Haydon, ed. W. B. Pope, 1963, 5.487). At this time Reynolds also volunteered to take on his nephew Samuel Johnson (the eldest son of his sister Elizabeth) as his pupil. His mother refused the offer, on the grounds that she considered Reynolds to be thoroughly degenerate, informing him that his soul was ‘a shocking spectacle of poverty’ (G. B. Hill, ed., Johnsonian Miscellanies, 1897, 2.455–6n.). Reynolds did not attend church. However, he seldom missed a social gathering of the Sons of the Clergy.

In 1779 rumours were circulated in the popular press concerning Reynolds's liaisons with the ‘amiable’ daughter of a naval officer and ‘Lady G—r’, who, it was said, sat to Reynolds in the evening as well as the morning so that ‘the knight should give a resemblance of her in the most natural way’ (Town and Country Magazine, Sept 1779, 401–4). His interest in Fanny Burney, whom he met in September 1778, shortly after the publication of her début novel, Evelina, is more certain. Over the next few years Reynolds (who was a close friend of her father) met Fanny Burney frequently, fuelling suspicions that he intended to offer her his hand in marriage. However, any prospect of nuptials was diminished in November 1782, when Reynolds suffered a severe paralysis. ‘How, my dear Sissy’, she told her younger sister:

can you wish any wishes about Sir Joshua and me? A man who has had two shakes of the palsy! What misery should I suffer if I were only his niece, from terror of a fatal repetition of such a shock! I would not run voluntarily into such a state of perpetual apprehension for all the wealth of the East. (Leslie and Taylor, 2.385)

Towards the end of his life, in 1788, Reynolds told Boswell he had never married, because ‘every woman whom he had liked had grown indifferent to him’ (Hudson, 137).

Home and abroad, 1780–1785

In 1780 Reynolds painted several works for the Royal Academy's private rooms at Somerset House, recently completed by Sir William Chambers. They included an allegorical figure, Theory, for the library ceiling, pendant portraits of George III and Queen Charlotte, and portraits of himself and Chambers for the academy's assembly room. At the annual exhibition of 1780 he showed seven works, including a striking full length of Lady Worsley in military riding attire (priv. coll.), a portrait of Edward Gibbon (priv. coll.), and an allegorical figure, Justice (priv. coll.). This last painting was one of seven Virtues made as designs for a painted glass window, the west window of New College, Oxford. The central design, a Nativity, had been exhibited at the Royal Academy the previous year, although the window itself was not completely installed until 1785. The final result, as Reynolds himself admitted, was disappointing.

In 1781 Reynolds exhibited fifteen works at the Royal Academy. They included a portrait of Charles Burney (NPG), Horace Walpole's nieces, the ladies Waldegrave (NG Scot.), and his young godson, Henry Edward Bunbury (Philadelphia Museum of Art). This picture remained in Reynolds's collection until his death when he bequeathed it to the boy's mother, his close friend Catherine Horneck. The portrait was described in the contemporary press as that of a boy ‘supposed to be listening to a wonderful story’, a comment which reflected Bunbury's own recollections that Reynolds had entertained him with fairy tales while sitting for the portrait (Whitley, 1.369). That year Reynolds also exhibited two major subject pictures, Thaïs (priv. coll.), modelled upon a notorious courtesan, Emily Pott, and The Death of Dido (Royal Collection), a composition inspired by his admiration for seventeenth-century Bolognese art and the antique (the central figure being an adaptation of a classical figure of Cleopatra in the Vatican).

During the 1780s Reynolds turned increasingly for inspiration to the art of Flanders and the Low Countries, an interest which prompted a two-month tour in the late summer of 1781. Accompanied by his Devon friend Phillip Metcalfe, Reynolds embarked from Margate to Ostend on 24 July, travelling to Ghent, Brussels, Mechelen, Antwerp, Dordrecht, The Hague, Leiden, Amsterdam, Utrecht, Düsseldorf, Cologne, Aachen, Liège, and Louvain, and returning via Brussels and Ostend. Reynolds was already well acquainted with Dutch and Flemish art, owning major works by Van Dyck, Rubens, Jordaens, and Rembrandt, genre paintings by ‘old Breughel’ and Teniers, and landscapes by Cuyp, Hobbema, Ruisdael, and van Goyen. Reynolds's detailed journal entries, which were intended ultimately for publication, reveal that the tour was organized around major private collections in the Low Countries and the great altarpieces of Flanders. Reynolds admired Dutch art, but its appeal was confined primarily to ‘the mechanical parts of the art’. ‘Painters’, he said, ‘should go to the Dutch school to learn the art of painting, as they would go to a grammar school to learn languages. They must go to Italy to learn the higher branches of knowledge’ (Reynolds, Journey, 110). He was unmoved by Rembrandt's Nightwatch, confessing that it was ‘with difficulty I could persuade myself that it was painted by Rembrandt’ (ibid., 91). He attributed it tentatively to Ferdinand Bol. Reynolds was less ambivalent about Rubens, whose art conformed more closely to his own tenets on the form and function of high art, and to the Italianate ideal, which remained his benchmark. He reserved his highest praise for Rubens's Conversion of St Bavo in St Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent, and his Virgin and Child with Saints in the Augustinuskerk, Antwerp. Even so, he was disturbed by the poor condition of many of these works which he had only known previously through engravings, observing sadly that the Descent from the Cross in Antwerp Cathedral was ‘chilled and mildewed’ (ibid., 31).

Reynolds went to Flanders once more in late July 1785, this time with the specific intention of purchasing pictures auctioned off by those religious houses and monasteries dissolved by the Holy Roman emperor, Joseph II. As a potential purchaser, Reynolds was deeply disappointed by the standard of work on offer, and bought nothing. However, in order that the visit would not be a complete waste of time he rapidly scoured the country, spending over £1000 in Antwerp on works by Rubens, Van Dyck, Snyders, and Murillo.

During the 1780s Reynolds made some headway in preparing notes from his journeys to Flanders and the Low Countries for publication, although they did not appear in print until after his death, when they were incorporated into the second volume of Malone's Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds. In 1783, however, Reynolds published a related piece of work, annotations to William Mason's translation of De arte graphica, Charles Alfonse Du Fresnoy's Latin poem of 1667 on colour theory. The timing was significant because, following his visit to Flanders, Reynolds was eager to express his current opinions on the primacy of colour. Less dogmatic than the Discourses, Reynolds's annotations on Du Fresnoy allowed him to make extensive comments on the art of Titian, Veronese, Watteau, and Rubens without qualifying his remarks with reference to the Roman school. The lessons learned from an intense study of Flemish art emerged forcibly in Reynolds's paintings of the 1780s. In 1782 Reynolds exhibited the Infant Academy at the Royal Academy. According to a contemporary critic the picture was painted immediately after Reynolds had returned from Flanders and thus ‘recollected all the beauty and force of colouring so characteristic of the Flemish School’ (St James's Chronicle, 30 April 1782). In 1786 Reynolds exhibited a portrait of Lady Anne Bingham (priv. coll.), which he himself referred to as ‘Sir Joshua's Chapeau de Paille’—a reference to Rubens's celebrated portrait (National Gallery, London), which he had seen in a private collection in Antwerp in 1781.

Reynolds's Victorian biographer, Tom Taylor, was among the first to speculate whether ‘Whiggism could have so preponderated his society and sitters had he not been a very decided Whig’ (Leslie and Taylor, 2.155). By the 1780s Reynolds's allegiance to the whig party was becoming increasingly evident, both in his choice of friends and in his portrait sitters. When Lord Rockingham finally came to power briefly in spring 1782, many of Reynolds's closest friends assumed key positions in government. They included Augustus Keppel, as first lord of the Admiralty, Lord Ashburton, as privy seal, Charles James Fox, as secretary of state, and Edmund Burke, as paymaster of the forces. In 1783 Burke, in the course of reinstating two Treasury officials accused of embezzlement, was satirically ‘observed to have a miniature of Count Ugolino, from Sir Joshua Reynolds, in his hand, in order to give sublimity to the description’ (Postle, Subject Pictures, 149). Johnson ruefully observed the increasing influence of Fox and Burke on his erstwhile protégé: ‘He is under the Fox star and the Irish constellation. He is always under some planet’ (Boswell, Life, 3.261). In April 1784 Reynolds exhibited Fox's portrait at the Royal Academy, just as Fox was engaged in a bitter election to retain his parliamentary seat at Westminster. At Fox's suggestion Reynolds included in the portrait his recently defeated East India Bill and his representation of the Commons to the king, the very policies that had precipitated George III into dissolving parliament.

On 1 October 1784 Reynolds was sworn in as principal painter-in-ordinary to the king, following the death of Allan Ramsay. Although the post conferred considerable kudos and a guaranteed income from replicating royal portraits, Reynolds poured scorn on the token annual salary of £50, complaining that the post was ‘a place of not so much profit and of near equal dignity with His Majesty's Rat-catcher’ (Letters, 112). Yet Reynolds coveted the post deeply, to the point of being prepared to resign the presidency of the Royal Academy. Ultimately Reynolds used his influence in the corridors of power to sway the issue in his favour, Thomas Gainsborough remarking that the post was originally to have been his except that Reynolds's friends ‘stood in the way’ (The Letters of Thomas Gainsborough, ed. J. Hayes, 2001, 161). Several weeks later, on 18 October, Reynolds was granted the freedom of the Painter–Stainers' Company at its annual dinner in the City of London.

Among the seventeen works which Reynolds exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1784 were a full-length military portrait of George, prince of Wales, reining in a charger (priv. coll.), a coquettish Nymph and Cupid (Tate collection), and a portrait, Mrs Siddons as ‘The Tragic Muse’ (Henry E. Huntington Art Gallery, San Marino, California. This last portrait was greeted by admirers as a form of ‘confined’ history painting, the general attitude of the figure being modelled upon the figure of Michelangelo's Isaiah from the vault of the Sistine Chapel. The enhanced aesthetic and intellectual appeal of Mrs Siddons was mirrored in the 1000 guinea price tag Reynolds placed on the picture. The price proved too high, and in 1786 the picture was still on Reynolds's hands, ‘which it would not be was this the period of the Tenth Leo, or the family of the Medici’ (Public Advertiser, 1 March 1786). In 1790 he sold it to a French collector for 700 guineas, then a record price for a portrait by Reynolds.

The later years, 1785–1790

The death of Samuel Johnson in December 1784 caused Reynolds to forge a closer bond with several mutual friends, and during the summer of 1785 what became known as ‘the Gang’ was formed by Reynolds, Boswell, Edmond Malone, and John Courtnay. Boswell and Reynolds were seen increasingly in public together, notably on 6 July 1785 when they attended the public execution of a former servant of Edmund Burke at Newgate gaol. In the same year Reynolds painted Boswell's portrait (NPG), which he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1787. ‘This is a strong portrait’, observed one critic, ‘and shews an artist can do with paint more than nature hath attempted with flesh and blood, viz—put good sense in the countenance’ (Morning Herald, 2 May 1787). Reynolds also acted as a general adviser on Boswell's Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides and, with Malone, encouraged him to complete his biography of Johnson, which was published in May 1791, with a dedication to Reynolds, ‘the intimate and beloved friend of that great man; the friend whom he declared to be “the most invulnerable man he knew; whom, if he should quarrel with him, he should find the most difficulty how to abuse”’.

During the mid-1780s Reynolds found new friends and patrons among a younger generation of intellectuals and connoisseurs, including George Beaumont, John Julius Angerstein, Abraham Hume, Henry Englefield, Richard Payne Knight, and Uvedale Price. Of these Beaumont was Reynolds's principal disciple, taking advice and painting lessons from Reynolds, and after his death erecting a cenotaph to his memory in the grounds of his country seat at Coleorton (celebrated in Constable's Cenotaph of 1836; National Gallery, London). Reynolds's most prestigious young patron, however, was George, prince of Wales, who in May 1786 sat to Reynolds for a full-length portrait (priv. coll.), commissioned by Louis Philippe, duc d'Orléans, and shown at the Royal Academy the following year. The picture was widely criticized owing to the prominent position in the centre of the composition of a black servant adjusting the prince's ceremonial robes, an idea that apparently came from the duc d'Orléans (The World, 27 November 1787). In 1786 Reynolds also painted a full-length portrait of the duc d'Orléans for the prince of Wales. Following its exhibition at the Royal Academy, the portrait was displayed at Carlton House, until early 1792, when it was abruptly moved, following the news that Orléans had voted for the execution of Louis XVI.

By the beginning of 1785 Reynolds's name was a byword for diligence: he was now working harder than ever, exhibiting seventy-nine pictures at the Royal Academy between 1785 and 1790. As The Times noted on 10 January 1785; ‘Sir Joshua Reynolds is shaved and powdered by nine in the morning, and at his canvass; we mention this as an example to artists, and as a leading trait in the character of this great painter’. Significant portraits from this period include Mrs Musters as Hebe (1785; Kenwood House, London), Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire and her Daughter (1786; priv. coll.), Lord Heathfield (1788; National Gallery, London), Lord Rodney (1789; Royal Collection), and Mrs Billington as St Cecilia (1790; Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, New Brunswick). Lord Heathfield, portraying the subject clasping the key to the rock of Gibraltar, rapidly acquired the status of an icon, Constable referring to it in the 1830s as ‘almost a history of the defence of Gibraltar’ (Leslie and Taylor, 1.517). It has recently been suggested that the picture may also have had religious overtones, through an intended comparison between Heathfield and St Peter, the great military hero transformed into ‘the rock upon which Britannia builds her military interests’ (D. Shawe-Taylor, The Georgians: Eighteenth-Century Portraiture and Society, 1990, 49).

While portraiture continued to be the mainstay of Reynolds's professional life, he now spent much of his time, particularly during the summer months, working on subject pictures. In 1782 he had exhibited a painting of a young girl leaning on a pedestal, a composition which he repeated on several occasions, and which became popularly known as the Laughing Girl (Kenwood House, London). In the mid-1780s he followed this up with a series of fancy pictures depicting little girls with pets: Robinetta with a robin, Lesbia with a sparrow, Felina with a cat, and Muscipula with a caged mouse. These paintings, light-hearted allegories on the theme of captive love, proved extremely popular and were extensively engraved and copied into the nineteenth century. In 1784 Reynolds exhibited a more overtly sensual picture on the theme of love, A Nymph and Cupid and in 1785 a Venus (priv. coll.)—‘a picture of temptation from her auburn lock to her painted toe’ (Public Advertiser, 5 April 1785). The popularity of Venus among his aristocratic patrons prompted Reynolds to repeat the composition several times, it being rumoured in 1787 that a version exported to France was destined for Louis XVI (Postle, Subject Pictures, 205).

In 1785 Reynolds received a prestigious commission for a historical painting from Catherine the Great. The subject chosen by Reynolds was The Infant Hercules Strangling the Serpents (Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg). He devoted more time and attention to this picture than to any picture he had ever painted, working on it intermittently between early 1786 and the spring of 1788, when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy. After completing the painting Reynolds admitted the difficulties he had encountered, observing that there were ‘ten pictures under it, some better, some worse’ (Northcote, Life, 2.219). In addition Reynolds painted two subject pictures for Prince Potemkin, a version of A Nymph and Cupid and The Continence of Scipio, shown at the Royal Academy in 1789, shortly before its departure for Russia. By this time Reynolds was also working on three subject paintings for Boydell's Shakspeare Gallery: Puck (priv. coll.), The Death of Cardinal Beaufort, and Macbeth and the Witches (both Petworth House, Sussex).

Reynolds's relations with Boydell were invariably strained. Having agreed in December 1786 to paint a scene from Macbeth, Reynolds was vexed to see himself described in Boydell's newspaper advertisement for the scheme as ‘Portrait-Painter to his Majesty, and President of the Royal Academy’. He sent Boydell a curt note:

Sir Joshua Reynolds presents his Compts to Mr. Alderman Boydell. He finds in his Advertisement that he is styled Portrait Painter to his Majesty, it is a matter of no great consequence, but he does not know why his title is changed, he is styled in his Patent Principal painter to His Majesty. (Letters, 176)

Reynolds was also unhappy at the very idea of being employed by Boydell, believing that he was ‘degrading himself to paint for a print-seller’ (Northcote, Life, 2.226). His reluctance to become involved was eventually overcome through the intervention of the Shakespeare editor George Steevens (Reynolds's friend and fellow member of the Club), and a large cash advance of £500 from Boydell for Macbeth, the canvas and stretcher for which he also supplied gratis.

In the late 1780s Reynolds appeared to be in good health, despite a considerable deterioration in his eyesight. His physical appearance at that time can be gauged from his self-portrait with spectacles of about 1788 (Royal Collection). Edmond Malone, to whom Reynolds presented a version of the painting, stated that the self-portrait with spectacles showed the artist ‘exactly as he appeared in his latter days, in domestick life’, suggesting that it was a private rather than a public image (Works, 1.1xxvii, note). That he presented copies of the portrait to Malone, Mason, and Burke suggests that it represented the way in which Reynolds wished to be seen by his close friends. Reynolds had worn spectacles at least since 1783, when he had complained of a ‘violent inflammation’ in the eyes. He had probably worn them for a lot longer, an examination of two pairs of his spectacles revealing that he was short-sighted, and would have needed spectacles to read and to paint (Penny, 337).

During the spring and early summer of 1789 Reynolds continued to take portrait clients virtually on a daily basis, including weekends. On Monday 13 July 1789 he had scheduled a 10 a.m. appointment relating to the double portrait of Miss Cocks and her niece (Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood House, London). On the same day he wrote in his sitter book, ‘prevented by my Eye beginning to be obscured’, the first reference to the failing sight in his left eye. Reynolds attempted to carry on with scheduled portrait sittings over the next few days, although within less than a week he was compelled to stop, the portrait of the misses Cocks being completed by another hand.

Within a fortnight Reynolds's retirement was announced in the press:

Sir Joshua has mentioned to several of his friends that his practice in the future will be very select in respect to portraits, and that the remnant of his life will be applied chiefly to fancy subjects which will admit of leisure, and contribute to amuse. Sir Joshua feels his sight so infirm as to allow of his painting about thirty or forty minutes at a time only and he means in a certain degree to retire. (Morning Herald, 27 July 1789)

The blank pages of the two remaining sitter books, punctuated only by details of social calls and business matters, reveal that by the end of July 1789 Reynolds had all but retired. His friend urged him to seek medical attention. ‘We are all uneasy about him from his plethorick habit’, observed Malone to Boswell, ‘lest he should have some stroke’. ‘If anything should happen to him’, he added, ‘the chain of our society at least, would be sadly broken:—but let us hope for the best’ (Boswell's Correspondence, ed. F. Brady, 1986, 4.366).

During the early autumn of 1789 Reynolds's eyesight, and the calibre of medical treatment he was receiving, became a public talking point, as his supporters rallied to counter rumours that the president of the Royal Academy was by now a spent force. ‘It is suspected’, stated the Morning Post, on 9 September 1789,

that some artists who want to bring their own puny talents into estimation have magnified the state of Sir Joshua's disorder in order to injure his reputation, and profit, if possible, by the idea that his faculties begin to suffer too materially to admit of any future works of extraordinary vigour and beauty.

Although he continued to take a keen interest in the affairs of the Royal Academy, Reynolds was also undermined in his presidency. On 22 February 1790, following a disagreement with the academy's general assembly over its opposition to election of the Italian architect Giuseppe Bonomi to the vacant post of professor of perspective, Reynolds tendered his resignation as president, and his membership of the academy. On 13 March he was reinstated, although he never regained the respect he had formerly commanded.

Reynolds's painting activities were by now restricted to retouching and refurbishing works in his collection and those portraits which were already well under way. All the paintings he showed at the 1790 Royal Academy exhibition had been started by the summer of 1789. They included a full-length portrait of Sir John Fleming Leicester in the uniform of the Cheshire provisional cavalry (University of Manchester, Tabley House, Cheshire), repainted by James Northcote, and Francis Rawdon Hastings, second earl of Moira and first marquess of Hastings (Royal Collection). Lord Rawdon may be regarded as Reynolds's final full-length male portrait, since he was working with the sitter right up until the day when he recorded the onset of blindness in his left eye. His final female full-length portrait, completed less than a month earlier, was Mrs Billington in the Character of St Cecilia.

Although no longer capable of working full-time as a portraitist, Reynolds in February 1790 discussed sittings for a new portrait of the prince of Wales for Lord Charlemont. ‘In short’, Thomas Dundas told Lord Charlemont, ‘Sir J. is determined that your picture should be an original’ (Charlemont MSS, 117). However, although Reynolds recorded a single appointment with the prince in his pocket book on 17 February, nothing came of the proposal. By July 1790 Boswell reported that Reynolds was able to do little more than to ‘amuse himself by mending a picture now and then’ (Reynolds, Discourses, ed. Rogers, 405, n.2).