signed dated: "1883" and further signed with a monogram top left

Private Collection Swansea

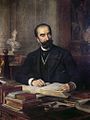

Illustration of Dixie by Théobald Chartran, published in Vanity Fair, 5 January 1884. A more significant lithograph, by Théobald Chartran, printed in colour, appeared in Vanity Fair in 1884 and is one of the long series of caricatures published in the magazine between 1868 and 1914. These were all coloured illustrations featuring notable people of the day, and each was accompanied by a short (usually adulatory) biography. Of more than two thousand people so honoured, only eighteen were women. Featured in the magazine on 5 January 1884, Dixie joined this small band, which included Queen Isabella II of Spain (1869), Sarah Bernhardt (1879), the Princess of Wales (1882) and Angela Burdett-Coutts, 1st Baroness Burdett-Coutts (1883). Victoria, Princess Royal, and Elizabeth, Empress of Austria, followed later in 1884.

Lady Florence Caroline Dixie [née Douglas], (1855–1905), author and traveller, was born in Kinmount, Cummertrees, Dumfriesshire, on 24 May 1855, one of a pair of twins, the youngest of the six children of Archibald William Douglas, eighth marquess of Queensberry (1818–1858), and his wife, Caroline Margaret (d. 1904), younger daughter of General Sir William Robert Clayton, bt.

.

The Douglases were an ancient Scottish family, vigorous and combative, and in Florence's generation they were haunted by disaster, dissension, and scandal: in 1858 Florence's father died from an accidental shot while cleaning a gun, dent, but was widely believed to have been suicide ; her brother Francis was killed in 1865 on the first ascent of the Matterhorn; James, Florence's twin, was to commit suicide in middle age in 1891; and their eldest brother, the ninth marquess of Queensberry (John Sholto Douglas), provoked the notorious Oscar Wilde case. Dissension affected the twins when they were seven years old and their mother alarmed their guardians by becoming a Roman Catholic and converting the children; she was threatened with the loss of her children, a real danger in an age which allowed a woman no rights over her own progeny, and an injustice against which Florence was to campaign in later life and which was the subject of her autobiographical The Story of Ijain (1903).

Their mother took the children abroad for two years and on their return, Florence was sent to a convent school where she hated the repressive regime and the dogmatism of the religious teaching. She found relief in poetry, writing Songs of a Child under the pseudonym Darling—verses which were not, however, published until 1902. Early in life she developed a passion for sport and travel. She was a firstrate horsewoman and a keen hunter of big game, one of the first women to take up this activity. She learned to swim and was a rapid walker. On 3 April 1875 she married Sir Alexander Beaumont Churchill Dixie, eleventh baronet (1851–1924), a strikingly handsome man, nicknamed Beau. They shared a taste for adventure and outdoor life, and the one flaw in an otherwise equal partnership seems to have been Beau's love of gambling, which was to prove a constant threat to the family property at Bosworth Park in Leicestershire, eventually sold to pay his debts. They had two sons, George Douglas (1876–1948) and Albert Edward Wolston (1878–1940), godson of the prince of Wales.

Several members of the Queensberry family were affected by mental illness. As mentioned above, Lady Florence's father is believed to have committed suicide. Her twin brother, Lord James Douglas (known to his family as Jim), was deeply attached to her and was heartbroken when she married. In 1885, he tried to abduct a young girl, and after that became ever more manic. In 1888, he married a rich woman with a ten-year-old son, but this proved disastrous. Separated from his twin sister 'Florrie', James drank himself into a deep depression and in 1891 committed suicide by cutting his throat.

Lady Florence's eldest brother, the 9th Marquess of Queensbury, is remembered for his contribution to the sport of boxing and to the downfall of the writer Oscar Wilde. The Queensberry rules for the sport of boxing, written in 1865 by John Graham Chambers and published in 1867, were endorsed by the young Queensberry, an enthusiastic amateur boxer, and thus took his name. In 1887, Queensberry and his wife Sibyl Montgomery were divorced. During the 1890s, their youngest son, Lady Florence's nephew, Lord Alfred Douglas (1870–1945), had a close relationship with Wilde, to the growing fury of his father, who accused the writer of "posing as a somdomite" (sic). Wilde sued Queensberry for libel, a bold step which ultimately led to his downfall and imprisonment.

Lady Florence's great-nephew Raymond Douglas (1902-1964), the only child of Lord Alfred, spent most of his life in a mental hospital.

Neither domestic nor social life appealed to Lady Dixie, and, having accomplished the duty of motherhood, she determined to escape 'the monotony of society's so-called pleasures' (Dixie, 2). In December 1878 she set off for South America where 'scenes of infinite beauty and grandeur' might be lying hidden in the solitude of the mountains which bound the barren plains of the Pampas, into whose mysterious recesses no one had yet ventured. 'And I was to be the first to behold them: an egotistical pleasure, it is true; but the idea had a great charm for me' (Dixie, 3). She was accompanied by her husband, her eldest and her twin brothers, and a friend, Julius Beerbohm, a naturalist with some knowledge of the country. Although she was the only woman in the party she took the lead throughout their six months abroad, not only in the pursuit of the big game with which they stocked their larder but also in coping with emergencies varying from the entertainment of unexpected visitors to the devastating shock of an earthquake.

The publication of Across Patagonia (1880) established Lady Dixie's reputation as a bold and resourceful traveller with a pen as ready as her gun. It was also partly the reason for her appointment as the Morning Post's war correspondent in South Africa where the Anglo-Zulu War was raging; she was the first woman to be officially appointed by a British newspaper to cover a war. Her husband accompanied her and, although on arriving in Cape Town in March 1881 they found to her chagrin that hostilities were over, they spent the next six months in southern Africa. They toured the country, visiting the battlefields and learning something of the causes and the course of the late conflict, while Lady Dixie contributed articles to the Morning Post in which she championed the cause of Cetewayo and his Zulu people. These provided material for A Defence of Zululand and its King (1882). The same views were expressed in her account of the South African adventure, In the Land of Misfortune (1882), a more serious work than Across Patagonia though it has its lighter moments. In some of these Beau is made to cut a less than heroic figure, as when he sleeps through the invasion of their tent by errant mules which his wife is left to drive out—or so she alleges (In the Land of Misfortune, 372).In 1881, Dixie was appointed as a field correspondent of the Morning Post of London to cover the First Boer War (1880-1881) and the aftermath of the Anglo-Zulu War. Her husband went out to South Africa with her. In Cape Town, she stayed with the Governor of the Cape Colony. She visited Zululand, and on her return interviewed the Zulu king Cetshwayo, who was being held in detention by the British. Her reports, followed by her A Defense of Zululand and Its King from the Blue Book (1882) and In the Land of Misfortune (1882), were instrumental in Cetshwayo's brief restoration to his throne in 1883. In Dixie's In the Land of Misfortune, there is a struggle between her individualism and her identification with the power of the British Empire, but for all of her sympathy with the Zulu cause and with Cetshwayo, she remained at heart an imperialist.

Dixie played a key role is establishing the game of women's association football (soccer), organizing exhibition matches for charity, and in 1895 she became President of the British Ladies' Football Club, stipulating that "the girls should enter into the spirit of the game with heart and soul." She arranged for a women's football team from London to tour Scotland. Dixie was an enthusiastic writer of letters to newspapers on liberal and progressive issues, including support for Irish Home Rule. Her article The Case of Ireland was published in Vanity Fair on May 27, 1882. Nevertheless, she was critical of the Irish Land League and the Fenians, who in 1883 made an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate her. As a result, Queen Victoria sent her servant John Brown to investigate.

On her return to England, home politics engaged Lady Dixie's attention, particularly those affecting Ireland which she saw as another ‘land of misfortune’ in need of her support. She was strongly in favour of home rule (as also for Scotland) but opposed measures advocated by the Land League during the agitations of 1880–83, thereby incurring the enmity of the extremist Fenians. On 17 March 1883, when Fenian outrages were exciting London, she announced that, while she was walking by the Thames near Windsor, two men disguised as women, whom she inferred to be Fenian emissaries, vainly attempted her assassination. Her statement attracted worldwide attention, but Sir William Harcourt, the home secretary, declared in the House of Commons that the story was unconfirmed, and nothing further followed.

Lady Dixie's political interests were thenceforth concentrated on the advocacy of complete sex equality. Her aims ranged from the reform of female attire to that of the royal succession law, which, she held, should prescribe the accession of the eldest child, of whichever sex, to the throne. She desired the emendation of the marriage service and of the divorce laws so as to place man and woman on the same level. She formulated such views in Gloriana, or, The Revolution of 1900 (1890); her stories for children, The Young Castaways, or, The Child Hunters of Patagonia (1890) and Aniwee, or, The Warrior Queen (1890) had a like purpose. Latterly, financial difficulties caused her and her husband to give up their home in Leicestershire and to settle on her family's Kinmount estate.

Dixie held strong views on the emancipation of women, proposing that the sexes should be equal in marriage and divorce, that the Crown should be inherited by the monarch's oldest child, regardless of sex, and even that men and women should wear the same clothes. She was a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, and her obituary in the Englishwoman's Review emphasized her support for the cause of women's suffrage (i.e. the right to vote): "Lady Florence... threw herself eagerly into the Women's Movement, and spoke on public platforms."

In 1890, Dixie published a remarkable utopian novel, Gloriana, or the Revolution of 1900, which has been described as a feminist fantasy. In it, women win the right to vote, as the result of the protagonist, Gloriana, posing as a man, Hector l'Estrange, and being elected to the House of Commons. The character of l'Estrange is clearly based on that of Oscar Wilde. The book ends in the year 1999, with a description of a prosperous and peaceful Britain governed by women. In the preface to the novel, Dixie proposes not only women's suffrage, but that the two sexes should be educated together and that all professions and positions should be open to both. In this preface, she goes farther and says:

“ Nature has unmistakeably given to woman a greater brain power. This is at once perceivable in childhood... Yet man deliberately sets himself to stunt that early evidence of mental capacity, by laying down the law that woman's education shall be on a lower level than that of man's... I maintain to honourable gentlemen that this procedure is arbitrary and cruel, and false to Nature. I characterise it by the strong word of Infamous. It has been the means of sending to their graves unknown, unknelled, and unnamed, thousands of women whose high intellects have been wasted, and whose powers for good have been paralysed and undeveloped. ”

During the 1890s, Dixie's views on field sports changed dramatically, and in her book The Horrors of Sport (1891) she condemned blood sports as cruel.

The New York Times dated March 19, 1883, reported an attack on Lady Florence Dixie by two men disguised as women, under the heading A DASTARDLY IRISH CRIME AN ATTEMPT TO ASSASSINATE LADY FLORENCE DIXIE. SHE IS WAYLAID BY TWO MEN DISGUISED IN WOMEN'S CLOTHES - HER LIFE SAVED BY A ST BERNARD DOG.

The New York Times dated March 30, 1883, carried a further story headed "LADY FLORENCE DIXIE'S OWN STORY. From the Pall Mall Gazette of March 19".

Reports are published of an attempt to assassinate Lady Florence Dixie at her residence, the Fishery, situated near the Thames, and about two and a half miles from Windsor. Lady Florence Dixie gives the following account of the occurrence:

“ I was out walking near the Fishery last evening, about 4:30, when two very tall women came up and asked me the time. I replied that I had not got my watch with me, and, turning, left them. Opening a small gate which led into the private grounds of Capt Brocklehurst, of the Blues, I made toward a stile, and was just going to get over, when I heard the gate open behind, and the two women followed me in. Somehow or other I felt all was not right, so I stopped and leaned against the rails, and then, as they came on, went to meet them. One on the right came forward and seized me by the neck, when by the strength of the clutch I felt it was no woman's power that pulled me down to the ground. In another second I saw the other would-be woman over me, and remember seeing the steel of the knife come right down upon me, driven by this person's hand. It struck through my clothes and against the whalebone of my stays, which turned the point, merely grazing the skin. The knife was quickly withdrawn and plunged at me again. I seized it with both hands and shouted as loud as I could, when the person who first pulled mr down pushed a large handful of earth into my mouth and nearly choked me. Just as the knife was wrenched from my hands, a very big and powerful St. Bernard dog I had with me broke through the wood, and the last thing I remember was seeing the person with the knife pulled backward by him. Then I heard a confused sound of rumbling of wheels, and I remember no more. When I came to myself I was quite alone. From what I saw of the knife I believe it to be a dagger, and the persons were undoubtedly men. They were dressed in long clothes, and were unnaturally tall for women; the one who stabbed me had on a thick veil, reaching below the mouth; the other was unveiled, but his face I did not notice much. This is all the information I can give. My head is very confused and painful, and I expect they must have stunned me. This is a wretched scrawl, but my hands are very much cut, and it pains me so much to write. ”

Lady Ripon and Sir H. Ponsonby called yesterday with a message of sympathy from the Queen to Lady Florence.

However, the New York Times of April 8, 1883, carried a further report:

LONDON, March 21 - It has been boldly suggested by the St. James's Gazette that Lady Florence Dixie is labouring under a mistake in regard to the dramatic occurrence which has occupied so much attention during the last 48 hours. Possibly when this reaches you its boldness will have been justified. The Tory journal does not believe that her ladyship has been attacked at all. Others share this opinion. In a week's time, the general public may share it.

When Dixie died in November 1905, the New York Times carried a report headed LADY FLORENCE DIXIE DEAD This stated that the "Author, Champion of Woman's Rights, and War Correspondent" had died on November 7th "at her home, Glen Stuart, Dumfriesshire", and included the following passage: Lady Florence Dixie was a member of the Queensberry family and inherited the eccentricities as well as the cleverness possessed by so many members of it. Some years ago she startled London by declaring that she had been kidnapped she believed by Irish agitators, and had been held for some days in captivity. Her story was never disproved, but neither was it proved, and there were many people who said that the whole affair was imaginary.

Lady Florence Dixie's eldest son, George Douglas Dixie (18 January 1876–25 December 1948) served in the Royal Navy as a midshipman and was commissioned into the King's Own Scottish Borderers in 1895. On 26 November 1914, he was promoted a temporary captain in the 5th Battalion the KOSB. He married Margaret Lindsay, daughter of Sir Alexander Jardine, 8th Baronet, and in 1924 succeeded to his father's title and was known as Sir Douglas Dixie, 12th Baronet. When he died in 1948, Sir Douglas was succeeded by his son Sir (Alexander Archibald Douglas) Wolstan Dixie, 13th and last Baronet (8 January 1910–28 December 1975). Married Dorothy Penelope (Lady Dixie) King-Kirkman in 1950 as his second wife, and they had two daughters; 1) Eleanor Barbara Lindsay; and 2) Caroline Mary Jane. Both daughters have issue.

Lady Florence Dixie's grandson Sir Wolstan Dixie wrote an autobiography called Is it True What They Say About Dixie? The Second Battle of Bosworth (1972). The title alludes to a 1940s song by Irving Caesar, Sammy Lerner and Gerald Marks recorded by Al Jolson in 1948.

In later life she became convinced of the cruelty of blood sports, which she denounced in Horrors of Sport (1891) and the Mercilessness of Sport (1901). She also supported secularism, contributing to the Agnostic Journal. Lady Dixie died at Glen Stuart, Annan, Dumfriesshire, on 7 November 1905, and was buried in the family grave at Kinmount.

Théobald Chartran (20 July 1849 – 16 July 1907) was a classical French propaganda painter and portrait artist.

Chartran was born in Besançon, France on 20 July 1849. His father was Councilor at the Court of Appeals and he was the nephew of Gen. Chartran who was executed in the Restoration because of his imperialistic tendencies. Through his mother, he was descended from Count Théobald Dillon, who was murdered by his own troops in 1792.

While his parents encouraged him to study law or enter the military, young Chartran was inclined towards art. He studied at the Lycée Victor-Hugo de Besançon before heading to Paris in order to devote himself entirely to the study of art under Alexandre Cabanel, later attending the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

In 1871, the body of Georges Darboy, the Archbishop of Paris, "who had perished in the disorders of the commune", was exhumed in order to receive the last honors, and Chartran made a portrait of the Archbishop in his official robes and on his catafalque. This painting was widely admired by the public and for it, he won the Grand Prix de Rome in 1877.

As "T", he was one of the artists responsible for occasional caricatures of Vanity Fair magazine, specializing in French and Italian subjects. His work for Vanity Fair included Pope Leo XIII, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Umberto I of Italy, William Henry Waddington, all in 1878, Charles Gounod, Giuseppe Verdi, Ernest Renan, Jules Grévy, Napoléon Joseph Charles Paul Bonaparte, Victor Hugo, Marshal MacMahon, Granier de Cassagnac, Louis Blanc, and Alexandre Dumas fils, all in 1879.

Among Chartran's work is his portrait of René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laennec, the inventor of the stethoscope, Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, Benoît-Constant Coquelin, the Maharaja of Kapurthala and the Countess of Maupeou.

President Roosevelt

In 1899, Henry Clay Frick commissioned Chartran to create a painting of the scene when the peace protocol at the close of the Spanish–American War was signed in the Cabinet Room. In October 1903, Frick gifted the picture, which had cost $20,000, to the United States, which President Roosevelt accepted.

In 1902, Chartran was commissioned to paint President Theodore Roosevelt's official portrait after successfully completing portraits of Mrs. Roosevelt in 1902 and Alice Roosevelt in 1901. In discussing his experience with painting the president to Le Figaro, he said that it "was difficult to get the President to sit still. I never had a more restless or more charming sitter. He speaks French like a boulevardier, and wittily." Chartran "did not try to depict the official Roosevelt, but rather the private man." When Roosevelt saw the final product he hated it and hid it in the darkest corner of the White House. When family members called it the "Mewing Cat" for making him look so harmless, he had it destroyed and hired John Singer Sargent to paint a more masculine portrait.

-

René Laënnec – National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland, USA

-

Edith Roosevelt's official portrait as First Lady (1902)

-

Théobald Chartran – Washington A. Roebling – Brooklyn Museum

-

Cardinal James Gibbons (1904), National Portrait Gallery

Chartran was married to a woman who "descended from a famous family" and was "gifted with a voice of sweetness and considerable power and possessed of strong lyric ambition, which, however, she did not gratify by a career on the stage." Her portrait appeared in The Pall Mall Magazine in 1906.

In September 1900, Chartran acquired the Île de Salagnon (also known as "Swan Island"), one of the five islands on Lake Geneva, located between Vevey and Montreux. On the island, he had a Florentine villa built by architect Louis Villard, as well as a small port. There, Chartran organized sumptuous evenings with illustrious characters and fireworks. When he died, the island was taken over by a Russian count, a Zurich merchant, and then an American, Mary Shillito. Today it is known as Villa Salagnon.

His wife died just before his last visit to America in January 1906. Chartran died in Paris on 16 July 1907.