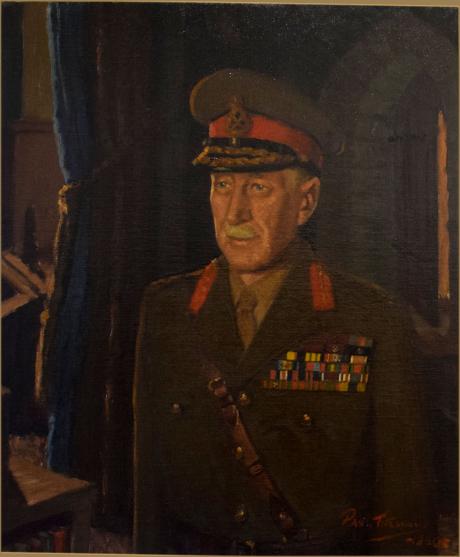

"Paul Fitzgerlad 1950"

Bernard Cyril Freyberg, first Baron Freyberg (1889–1963), army officer and governor-general of New Zealand, was born on 21 March 1889 at 8 Dynevor Road, Richmond, Surrey, the son of James Freyberg (1827–1914), a land agent and surveyor, and his second wife, Julia Hamilton (1852–1936). He was his father's seventh son, but the fifth son of his father's second marriage. Very little is known about either parent: his Scottish-born mother may have had some university education and taught her children until they went to secondary school. In 1891 James Freyberg left London and took his family to Wellington, New Zealand, where he found employment in the forestry department.

James Freyberg died in 1914 but his widow lived on until 1936 and clearly exerted a lasting influence on her son. He attended Wellington College (1897–1904), a free state school for boys, until his fourteenth year, when his father apprenticed him to a dentist. Although he was not academically inclined it was at school that he began his military career, becoming a sergeant in the cadets. A noted swimmer, he competed in the 1905 Australian championships in Sydney and Brisbane, won the New Zealand junior championship in 1906, and the senior championship in 1910. Nicknamed Tiny, a schoolboy contradiction of his height of more than 6 feet, Freyberg also played rugby, rowed, boxed, and sailed. His dental apprenticeship in Wellington until 1907 was followed by employment as a dentist in Morrinsville, Hamilton, and Levin. Unfortunately he had been unaware of the Dental Act of 1904 which introduced a four-year university degree course. Freyberg, in 1907, joined in a petition to parliament for an amended act. There followed a brief, unsuccessful period at Otago University in 1910, a further petition to parliament, and final professional registration as a dentist in May 1911.

Between 1905 and 1907 Freyberg belonged to D battery of the New Zealand field artillery volunteers in Wellington. A more positive step in his military career was his commission as a second lieutenant in the territorial sixth Hauraki regiment in late 1911. A dock and shipping strike in Wellington brought Freyberg to Wellington as a special mounted constable in 1913 and it was during this unrest that he crossed to Sydney several times as a volunteer stoker. A brief return to dentistry, which he never liked and of which he never spoke, decided Freyberg to seek a better life overseas. At the end of March 1914 he sailed for San Francisco, USA. What he did during the following four months is full of uncertainty but it seems probable that Freyberg, as a security guard for a film company, went to Mexico where late in June 1914 he may have seen some action in the civil war in the force commanded by General Francisco ‘Pancho’ Villa. Two months later, on 5 August 1914, the First World War broke out and by the end of the month Freyberg was in England.

Gallipoli and the western front

In London Freyberg lost no time in seeking a commission. On the advice of G. S. Scholefield, a New Zealand press representative, he saw Major G. S. Richardson, New Zealand's liaison officer at the War Office, who was then on the staff of the Royal Naval division. The latter had also been a member of Wellington's D battery. The upshot was that Freyberg was given a temporary commission as a lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and posted to the Hood battalion of the 2nd Royal Naval brigade, soon to be promoted lieutenant-commander, commanding A company. He also met Winston Churchill, first lord of the Admiralty and champion of the naval division, who may have played a part in securing his commission (Freyberg, 37).

In September 1914 Antwerp, covering the vital channel ports, was threatened by advancing German forces. To reinforce the insufficient Belgian army the Royal Naval division was ordered to Antwerp in the first week of October. Freyberg's A company Hood battalion had its first taste of action and joined the withdrawal on 8 October. Freyberg, reconnoitring a route, received his first wound from an electrified fence which severely burned his hand. He returned to England and was at Crystal Palace and Blandford with the Royal Naval division, regrouping and training until 27 February 1915 when it was sent to the Middle East for the Gallipoli campaign. It was an important period in Freyberg's development, both in a military sense, for he lacked experience and, particularly, in the opportunity to learn, observe, and assimilate the social and intellectual patterns then available to him. His fellow officers, the ‘Argonauts’, have often been described as the cream of young British manhood. Arthur Asquith, Rupert Brooke, Denis Browne, and Patrick Shaw-Stewart were A company officers. These and others opened social and political doors that included those of Prime Minister Asquith and First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill.

As a preliminary to the action Freyberg played a part in the burial of Rupert Brooke on the island of Skyros on 23 April 1915, helping to select the site and, with other officers, covering the grave with a cairn of marble rocks. During the action at Gallipoli itself, Freyberg won renown with a long swim on the night of 25–26 April, towing a bag of flares to shore at the beach below Bulair in the Gulf of Saros, there to deceive the Turks that a major landing was taking place. For this exceptional exploit he was awarded the DSO. Freyberg later took part in the badly conceived actions to capture Achi Baba and had temporary command of Hood battalion from 25 June 1915, relinquishing it when he was shot in the stomach about a month later. A rapid recovery in hospital in Egypt led to a return to Gallipoli in mid-August, when he was promoted commander to lead the battalion in a reorganized Royal Naval division. After a further three months in and out of the front line Freyberg joined the general evacuation and left Gallipoli with the battalion rearguard at 2.30 a.m. on 9 January 1916. The battalion was able to parade only fifteen men from its original establishment.

Back in London Freyberg decided to pursue a permanent career in the forces and applied for a transfer to the British army where his new contacts opened horizons of great opportunity. On 19 May 1916 he was gazetted captain in the Royal West Surrey regiment and temporary lieutenant-colonel commanding the Hood battalion which was concentrated on the western front by 24 May 1916. Training and routine followed until the Royal Naval division, now transferred to the British army as 63 division, took part in the battle of the Somme in October. It was here, on 13 November 1916, during the battle of the Ancre, that Freyberg, amid quite incredible scenes of chaos and carnage, displayed conspicuous bravery and leadership during the capture of the village of Beaucourt. After two relatively minor wounds he was gravely wounded in the neck and eventually evacuated, but he refused to leave until the advanced position had been consolidated against counter-attack. For his role in the action Freyberg was awarded the Victoria Cross. It was mid-February 1917 before he was sufficiently healed to return to the Hood battalion.

For Freyberg the three-month recovery period in London was to produce two new elements that were to affect him for the rest of his life. He was introduced to the dramatist J. M. Barrie, who became one of his greatest friends and who encouraged his dormant but undoubted ability to write. And he renewed his acquaintance with Barbara McLaren (1888–1973), whose husband, Francis, was killed in August 1917 and who became his wife on 14 June 1922. As the daughter of Sir Herbert and Lady Jekyll, and widow of the son of the first Baron Aberconway, she provided not only an excellent family background but also an effective partner in all his future undertakings. Their only son, Paul, was born in 1923.

On 20 April 1917 Freyberg was posted to command 173 brigade in 58 division: at the age of only twenty-eight he was the youngest brigadier-general in the British army. Between 12 and 20 May there was severe and costly fighting at Bullecourt. Despite high casualties Freyberg felt that his careful training regime had greatly increased the morale and fighting capacity of his brigade. At the end of August 1917 his division was transferred from Third to Fifth Army in preparation for an attack at Passchendaele. After difficult preliminaries in shell-swept mud the battle of Menin Road began on 20 September. That same day Freyberg was severely wounded, penetrated in five places by a bursting shell. He was hospitalized until the end of November.

On 21 January 1918 Freyberg was appointed to command 88 infantry brigade in 29 division, then in the area south of Ypres. Here he was in and out of the line, training and reshaping his brigade until 21 March when the Germans began their last great offensive in the Somme. The brigade contested an engulfing sea of mud until 10 April, when it was ordered to halt a German thrust south of Ypres, near Bailleul. Amid the chaos Freyberg added other infantry companies, artillery batteries, engineers, and stragglers to his command and held the line. Minor but costly operations followed for the next five months. On 3 June Freyberg had been wounded for the ninth time but was not evacuated.

After a major thrust westwards from Ypres at the end of September Freyberg was awarded a bar to his DSO. By 11 November his brigade was some 10 miles short of the River Dendre. Ordered to capture the bridges at Lessines, Freyberg, on horseback with a squadron from 7 dragoon guards, achieved this just moments before the armistice. He was awarded a second bar to his DSO for this venture. On 13 December 29 division crossed the Rhine at Hohenzollern Bridge to take part in the occupation. For Freyberg the war was over.

Reverting to the substantive rank of captain, Freyberg applied for a regular commission in the Grenadier Guards in March 1919. He was sent to Staff College, Camberley, for most of 1919 and in February 1920 was posted to 1st battalion Grenadier Guards. Dogged by ill health caused by incompletely healed wounds, Freyberg left for a six-week sea journey to New Zealand in May 1921 in order to recover his health and visit his mother. Back in England he was appointed GSO2 in 44 (Home Counties) division at Woolwich.

Freyberg made his first unsuccessful attempt to enter parliament, as Liberal candidate for Cardiff South, in 1922. Soldiering had not entirely ousted his earlier ambitions, and he made three attempts to swim the English Channel, failing narrowly in August 1925, and again the following August. He was posted back to 1st battalion Grenadier Guards on 26 January 1926 and became a substantive major with a brevet for lieutenant-colonel in October 1927 when posted as GSO2, headquarters eastern command, at the Horse Guards. In March 1929 he was given command of the 1st battalion of the Manchester regiment at Shorncliffe near Folkestone. It was here that he wrote most of A Study of Unit Administration, published in 1923, setting out the need for a commanding officer to ensure economical and sensible administration that would have particular regard for the welfare of the troops, especially in matters of diet.

Early in 1931, as colonel, with backdated seniority to 1 January 1922, Freyberg was appointed assistant quartermaster-general southern command, then in 1933 as GSO1 at the War Office. On 16 July 1934 he was promoted major-general, soon to be on half pay until a suitable posting came up. This was in January 1935 when he was appointed general officer commanding (GOC) in the presidency and Assam district of the eastern command of India. Fate intervened when routine medical boards detected an irregular heart beat and the appointment was cancelled. After much medical discussion Freyberg was placed on retired pay in September 1937. It could have been little consolation that he was created CB in February 1936.

Freyberg failed to win the Conservative candidacy for the Ipswich constituency in 1938. Offered the candidacy for the Spelthorne division of Middlesex in 1940, he was unable to stand because of military commitment. He became a director of the Birmingham Small Arms Company in 1938, and he supervised the erection of fifteen houses on properties inherited by his wife. On 3 September 1939, under a medical grading which declared him fit for home service only, he took up appointment as GOC Salisbury Plain. Nevertheless, Freyberg got himself graded medically fit for active service by a Salisbury medical board on 11 October, and had this confirmed on 2 November by a doubtless surprised War Office medical board, with the reservation that he was fit for active service only in temperate climates, a grading he retained for the whole of the Second World War.

Commander of New Zealand forces

New Zealand declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939; and Freyberg offered his services to the New Zealand government on 16 September while carrying on with his major task of preparing units for dispatch to France. On 4 November Peter Fraser, New Zealand's deputy prime minister, in London for a meeting of dominion ministers, arranged to meet Freyberg, was very favourably impressed, and after discussions with his own government, the chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), General Ironside, General Gort, and Winston Churchill was able to inform Freyberg on 16 November that he would command New Zealand's expeditionary force (2NZEF).

After a short visit to France, Freyberg went to New Zealand to consult with government and to get to know as many of his senior officers as he could reach. A charter was drawn up defining his dual role as a servant of the New Zealand government, which was uppermost, and as a subordinate of the commander-in-chief of the forces to which he might be attached. He was given a great deal of discretion and, as commander 2NZEF, with its necessary non-divisional units—medical, engineering, administrative and so on—had a much greater command than that of a divisional commander in a British corps. Unlike the commander of the Australian forces, who was ranked in the Australian army, he was a British officer on loan to New Zealand.

Freyberg's effectiveness did not come into serious contention until the ill-advised campaigns in Greece and Crete in March and April 1941. Until then, from both the Middle East and England, to which about one third of the 2NZEF had been diverted in June 1940, he had assiduously consulted and advised the New Zealand government. As it became clear that the original plan of using Egypt as a staging and training base en route to action in France was no longer relevant, Freyberg's major efforts were directed to the concentration and training of his division in the Middle East. Owing largely to the political over-optimism of Anthony Eden in creating a Balkan front and the ambivalence of the service commanders, Freyberg failed to inform the New Zealand government of the risks and lack of equipment and air cover, associated with the campaign in Greece in the mistaken belief that Wavell or Eden had done this. Within the month of April 1941 the campaign in Greece, never militarily possible, was fought and lost. Freyberg, with about two thirds of 2nd New Zealand division less most of its equipment, was in Crete, with instructions from Wavell to command all allied forces there and to hold the island at all costs, a role he accepted with grave misgivings as a matter of duty.

Crete, north Africa, and Italy

On 20 May 1941 the expected German onslaught on Crete began. In the three weeks available to him Freyberg had positioned his forces which lacked artillery, armour, air cover and much normal infantry equipment. The Enigma decrypts had provided generals Wavell and Wilson with most accurate information about German plans and movements during the campaign in Greece: this had been extended to Crete on 18 April 1941 and Freyberg received it disguised as information supplied by a Secret Intelligence Service agent in Athens (Hinsley, 417). He accordingly covered the areas Maleme, Khania, Retimo, and Heraklion—and the Germans assumed that espionage had divulged their plan (ibid., 420). Debate will continue over whether Freyberg had the resources in men or material to hold Crete, and over his insistence on the need to cover a possible seaborne landing that was in fact smashed by the Royal Navy. Nevertheless, for whatever reason, the failure to deny the principal landing strip, Maleme, to the German airforce proved decisive. Certainly Freyberg pondered the problem for the rest of his life. However, the importance to Freyberg of the withdrawal actions in Greece and Crete eventually centred on his relationship with Prime Minister Peter Fraser who felt that he had committed 2nd New Zealand division without adequate consultation. Freyberg was able to satisfy Fraser on this count, though neither was aware of the degree of Eden's optimism and its impact on the information given to the Australian and New Zealand governments. Any doubts about Freyberg's leadership that Fraser may have had, due to complaints by a senior officer, were swept away after very warm commendations from the CIGS, Dill, and also from Wavell. For the remainder of the war Fraser had undeviating confidence in Freyberg, who never again failed to give explicit information.

By now the Germans had effectively reinforced the Italians in north Africa, which became Freyberg's battleground for the next two years. These years may be broken down into four main periods: the relief of Tobruk, November to December 1941; the battle for Egypt, June to July 1942; the deciding battles of Alam Halfa and Alamein, August and November 1942; and the pursuit to Enfidaville in Tunisia. It was in these battles, which swayed up and down in that narrow strip of north Africa between the Mediterranean and the pathless desert, that 2nd New Zealand division became Rommel's most feared opponent and which prompted Churchill to designate Freyberg the salamander of the British empire. As in France in the First World War, Freyberg led from in front at the cost of a severe neck wound from a shell splinter on 27 June 1942 at Minqar Qaim. His division, sometimes strengthened to corps status, became expert in the three vital desert operations: the set piece break-in attack; immediate pursuit; and the outflanking movement or left hook.

For Freyberg success depended on the will to win of a fully trained force at the highest pitch of physical fitness, capable of co-operating with all other arms. He was made a KBE in the New Zealand 1942 honours list for skilled leadership in Greece and Crete and an immediate KCB in November 1942 for his historic contribution at Alam Halfa and Alamein. On 1 March 1942 he was promoted temporary lieutenant-general at the request of the New Zealand government which was prompted to this action because the GOC Australian Imperial Force, who was junior to Freyberg, had been promoted to that rank on 27 March 1942. Perhaps his greatest prize was, while temporary commander of 10 corps, to accept the surrender of the Italian Field Marshal Messe, supreme axis commander in north Africa, on 13 May 1943. On 8 July 1943 Freyberg was restored to the active list of the regular army with seniority backdated to 2 November 1939. Lady Freyberg, who made a distinguished contribution to the war effort by organizing welfare for troops, was appointed OBE in 1943. In 1953 she became a GBE.

After Africa, Italy. Here the campaign against the occupying German forces, for Italy had surrendered, fell into two phases: the hard battles culminating in the fall of Cassino on 18 May 1944 and the pursuit to Trieste, the end of the war.

The successful Sangro River crossing ended in stalemate at Orsogna and Freyberg's division, trained and organized for mobile operations, was moved from the Adriatic coast to the command of the US Fifth Army in the west. The division was to be used in a pursuit role to and beyond Rome after a successful thrust from the Anzio landing. Largely because of failure to exploit initial success at Anzio, Freyberg—who believed that this would have been an ideal role for 2nd New Zealand division (Freyberg, 455)—was again faced with a static front culminating in the battle for Cassino. For Freyberg the bombing of the Abbey Monte Cassino has attracted almost more attention than the extremely costly and only partially successful operations of his division. Organized as NZ corps on 3 February 1944 with the inclusion of 4 Indian division, this force's task became the capture of Monte Cassino and Cassino township, both rendered almost impregnable by the cover provided by the bombed ruins. Freyberg, never sanguine that a frontal attack would succeed (ibid., 457), had made it clear to General Alexander that he would withdraw 2nd New Zealand division if casualties reached 1000. Accordingly, with the road to Rome still blocked at Cassino and New Zealand casualties at 998, plans were changed and 2nd New Zealand division began an outflanking move. Cassino fell by a combined assault on 18 May 1944. Freyberg had resumed command of 2nd New Zealand division on 27 March, the corps being disbanded.

Rome was entered on 4 June by the US Fifth Army and Freyberg, ever solicitous for the welfare of his troops, acquired the best hotel, the Quirinal, in the face of keen competition, for use as the NZ forces club. Freyberg's policy during the advance on Florence was to maintain pressure but to avoid major commitment. For him the period produced three major events: the fall of Florence on 4 August, a visit by Prime Minister Churchill on 24 August, and an aircraft accident during a visit to Eighth Army headquarters on 3 September. Freyberg was incapacitated until 14 October 1944 (Freyberg, 476–9). Thereafter he reorganized and retrained his division so that it could best meet the conditions demanded by the nature of the country, riven by stop banks and swiftly flowing rivers. There remained five distinct and major river crossings requiring set-piece attacks followed by immediate pursuit, given hands-on control and making use of Freyberg's unique skill matured in so many battles from Gallipoli, Flanders, north Africa, and finally Italy. The final stages of the war in Italy saw Freyberg directing a highly mobile division and attached arms in a spectacular advance to Trieste and the enemy surrender. He was awarded a third bar to the DSO and created commander of the US Legion of Merit.

Governor-general

Freyberg relinquished command of 2NZEF on 22 November 1945. He remained on the British army list with the rank of lieutenant-general until his retirement was announced on 10 September 1946. Freyberg's service to New Zealand was to continue, however. He was offered the position of governor-general of New Zealand in September 1945, being sworn in on 17 June 1946. He had received an honorary DCL from Oxford University in 1945, and became GCMG early in 1946. Freyberg later said that his six years as governor-general were the happiest of his life, combining a position of great responsibility with his pleasure in meeting—and in the case of former soldiers, greeting—very many people. Freyberg and his wife, Barbara (perhaps a little anxious that protocol would become secondary to Kiwi friendliness), constantly at his side, made a warmly appreciated and constitutionally effective pair. As well as carrying out the busy round of official duties and functions, visiting Pacific island dependencies and neighbours, including Australia, and preparing for royal visits by George VI and, after the king's illness, Princess Elizabeth, the Freybergs entertained and introduced to New Zealand many world leaders in politics, the services, and the arts. Field Marshal Montgomery, Anthony Eden, and Marie Rambert are but three examples. And with one of his wartime brigadiers, Major-General H. K. Kippenberger, a close personal friend, the editor-in-chief, he took a great and helpful interest in the preparation of the official war history. Working historians soon discovered his consuming interest in the battle for Crete. In 1951 Freyberg was created baron and took the title Baron Freyberg, of Wellington, New Zealand, and of Munstead in the county of Surrey. A final honour was bestowed on 3 July 1952 when Victoria University of Wellington conferred an honorary LLD. Amid unprecedented cheering crowds Lord Freyberg left Wellington for the final time on 15 August 1952.

Freyberg's final official position was that of lieutenant-governor and constable of Windsor Castle, which he had been asked to consider before he left New Zealand. Inspection of the Norman Tower, the official residence, revealed the need of updating, which included the provision of a lift for which Freyberg paid half the cost. Although appointed under the sign manual on 1 March 1953, the Freybergs did not occupy the Norman Tower until September 1954. Official duties included playing a leading role at Windsor Castle functions, for example, the conferring of the Order of the Garter on Winston Churchill. Freyberg also took a great interest in the proceedings of the House of Lords and spoke in some of the debates. He represented either the New Zealand services or government at such occasions as the Alamein reunion in 1952, sitting with Churchill, Alexander, and Montgomery, or at the dedication of memorials at Malta, Alamein, and Athens. Freyberg also played a role in the coronation of Elizabeth II. An event which gave him great personal satisfaction was the celebration of the centenary of the founding of the Victoria Cross when, on 26 June 1956, he commanded the Hyde Park parade of 297 holders of the award.

Reputation

After the First World War—young, handsome, and much decorated—Freyberg was able to settle down and make a career for himself. As a soldier in the Second World War he fully lived up to the criteria that he had set out as necessary qualifications for the general commanding New Zealand troops: that he should be able to conduct a retreat under heavy enemy pressure; that he could make a counter-stroke, force a river line, or conduct operations in open warfare involving co-operation of all arms; that he should be able to carry out effective artillery fire plans. All these qualities were required and were amply supplied in the battles of north Africa and Italy. Freyberg himself believed that his division's most memorable days were in its part in holding the axis forces in the Middle East until the allies were organized on a war footing, that is until ‘the turn of the tide’ at Alamein.

Should Freyberg have been promoted to commands greater than that of 2NZEF? He did of course command 10 corps in Tunisia, and in both north Africa and Italy his command was often swelled to corps size. And command of 2NZEF was very much more than command of a single division, with ultimate responsibility for the many non-divisional troops and services and the necessary contact with a government and a prime minister. Considering Freyberg's technique as a fighting general—to lead from in front, adopted in the Hood battalion and maintained to the very end at Trieste—his ability to hold the respect and loyalty of his quite remarkably talented senior officers, together with his success in his dealings with the New Zealand government, he was ideally placed where he was.

Freyberg as a divisional commander was well supported by his brigade and services commanders. He conducted orders groups before major engagements, with maps, sand trays or plaster models, and aerial photographs. Discussion was free and vigorous. In pursuit he became known for the cry ‘they've gone’, and instant conferences with leading brigade commanders could result in a stream of orders and suggestions until the relevant commander seized on one thought possible and made off. It was unorthodox, but it worked. He was known by sight to the rank and file—it was Field Marshal Slim who said that a division 'is the smallest formation that is a complete orchestra of war, and the largest in which every man can know you' (Slim, 3). Freyberg was greatly respected, though few were aware of his concern that New Zealand's 'one ewe lamb' should not be exhausted of manpower.

Of the many encomiums from his superiors, that from Montgomery spells it out: 'His example and infectious optimism were an inspiration to the whole army. Such outstanding leadership can rarely have been seen in the history of the British army' (B. L. Montgomery, introduction to Freyburg's report The New Zealand division in Egypt and Libya, unpublished, priv. coll.). While Montgomery was proud to have Freyberg and 2nd New Zealand division in Eighth Army, German documents reveal that they were most dreaded, and respected, by Field Marshal Rommel.

After the misunderstandings surrounding the defeats in Greece and Crete, Freyberg's relationship with the New Zealand government was excellent. Prime Minister Fraser wrote: 'We could have had no better Commander of our Expeditionary Force and never was a Commander more thoroughly and completely trusted' (Freyberg, 507). Of course he made mistakes, and his role in the débâcle in Crete will remain controversial. In addition, he failed to push ahead at Tebaga Gap in the Mareth line operations, after an easy break-in attack. Cassino, as he had advised corps and army commanders, could not be captured by frontal attack. Despite errors of judgement, which Freyberg shared with higher command, nothing can overshadow the record of the division which became synonymous with the name of its commander.

Freyberg, whose health was deteriorating with the onset of Parkinson's disease and hardening of the arteries of the brain, suffered a rupture of his Gallipoli stomach wound on 4 July 1963, and died later that night in King Edward VII Hospital, Windsor, aged seventy-four. He was buried at St Martha-on-the-Hill Church, Surrey, on the Pilgrims Way, on 10 July 1963.

- Ian Wards DNB

Paul Desmond Fitzgerald (1 August 1922 – 24 June 2017) was an Australian portrait painter who painted a vast array of distinguished persons.

Fitzgerald was born in the family home, in the Melbourne suburb of Kew, the second son of Frank Fitzgerald and Margaret née Poynton. Frank Fitzgerald was a journalist with The Age for approximately ten years and about eight years with The Argus. He periodically filled the roles of general reporting, leader writing, political correspondent, art critic, music critic, theatre critic and motoring editor.

A Catholic, Fitzgerald was educated at Xavier College in Melbourne (1933–1939) and studied for five years at the National Gallery School (1940–43 and 1946–47), interrupted for three and a half years in the Army during World War II (1943–46).

When he was painting away from his studio in Melbourne, he usually lived with the subjects of his portraiture. He lived and painted overseas on commissioned portraits twice each year since 1958 including America, Canada, England, Scotland, Ireland, Jersey, France, Italy, Germany, Spain, Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Hawaii and Bermuda. He also painted throughout Australia.

Fitzgerald was a finalist for the Archibald Prize for portraiture on multiple occasions including 1958 (with a portrait of Justice Robert Monahan), in 1962 (with portraits of each of Sir Reg Ansett and Sir Robert Menzies), and in 1972 (with a portrait of Sir Henry Bolte).

In 1997 Fitzgerald was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia and a Knight of Malta. He founded the Australian Guild of Realist Artists, where he was a Life Member of the Council, and was president for seven years. Fitzgerald was a member of "Portraits Incorporated" in America, is a trustee of the A.M.E. Bale Travelling Scholarship and Art Prize, and produced the art book Australian Realist and Impressionist Artists, donating the profits to charity.

Fitzgerald's work was prolific and the following are known notable portraits by the artist:

- Queen Elizabeth II in 1963, in 1978 being the only official portrait in her Silver Jubilee year, and one other portrait in 1967.

- Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh in 1976, plus one other portrait in 1974.

- Charles, Prince of Wales, two portraits, 1978.

- Pope John XXIII painted in The Vatican in 1963.

- The Duke of Kent, two portraits, in 1978 and 2000.

- Sir William Heseltine, Private Secretary to Queen Elizabeth II.

- Five portraits of the Malaysian Royal Family

- Two identical 6 feet (1.8 m) portraits of Sharafuddin Idris Shah -The Raja Muda of Selangor (Crown Prince of Malaysia), son of the Sultan of Selangor

- Prince Ludwig (nephew of Prince Philip) and Princess Von Baden and family (Germany)

- Three Cardinals, including Cardinal James Knox, four Archbishops including Daniel Mannix, and two Bishops

- Angelo de Mojana di Cologna – 77th Prince Grand Master of the Knights of Malta and Count Da Larocca – Knight of Malta

- The Duke of Westminster; a Marquess; three Earls; two Viscounts; four Barons

- Two Governors-General of Australia, two Australian Prime Ministers, including Sir Robert Menzies and Malcolm Fraser, six Australian State Governors, two Australian State Premiers, including Sir Henry Bolte

- Bernard Cyril Freyberg, first Baron Freyberg , Governor General of New Zealand

- Fourteen Supreme Court Judges, including portraits of the ten judges of the Supreme Court of Victoria between 1964 and 1965 (who were Sir Edmund Herring, Sir Charles Lowe, Sir Norman O'Bryan, Sir Arthur Dean, Sir Reginald Sholl, Thomas W. Smith, Sir Edward Hudson, Sir Robert Monahan, Sir Douglas Little, and Sir Alistair Adam) and six Chiefs of Air Staff

- Two presidents of the Australian Colleges of Surgeons, three of the College of Physicians: one the College of Anaesthetics and three of the College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; two presidents of the English Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Three University Chancellors; twelve College Principals

- Three Presidents of the Melbourne Cricket Club; seven Presidents of the Victorian Football League and three Chief Executives; two presidents the Australian Football League

- Five presidents of the Board of Governors of the New York Hospital; the Executive Director of the New York Hospital

- World Chairman of Citibank (who was also president of the New York Metropolitan Opera), Conrad Hilton (Hilton Hotels), Glenn Ford (actor), Vivien Leigh (actor), Maria Callas (soprano; posthumously)

- Two Australian motor racing champions

- Sporting champions including Sir Norman Brookes (post.), Lew Hoad, Neale Fraser, Allan Border,John Nichols, Lionel Rose

- S. Baillieu Myer

- Mrs Kerry Packer, Gretel & James

- Sir Reginald Ansett

- Peter Janson

- Hector Crawford

- Bruno and Reno Grollo

- Hon. Tom Hughes QC – Australian Attorney-General

- The first three Racehorses of the Year for Victorian Racing Commission – Rain Lover, Gay Icarus, Vain

- 14 portraits of the Vestey Family

- Portraits of Lord Trout, Roy Trout (1974), and Jane Nathan (1958)

- George Mochrie, 1970, Melbourne Businessman

Shortly after returning to Australia in 1957, Fitzgerald married Mary Parker, who was born in Bitton, Gloucestershire and, as a child, had emigrated with her family to Melbourne. Parker's brother, Lieutenant–Commander Michael Parker, was a former private secretary to Prince Philip. Mary Parker attended Genezzano Convent then returned to England and established a successful career as a film actress and television announcer. She returned to Australia with HSV-7 in 1956 to cover the television coverage of the Melbourne Olympic Games and is considered to be the first woman on Australian television, having appeared in their test broadcasts and as a newsreader on their opening night, alongside Eric Pearce (later Sir Eric). Mary and Paul Fitzgerald had seven children; Fabian (born 1959), Marisa (born 1960), Patrick (born 1963, since deceased), Emma (born 1964), Edward (born 1968), Maria (born 1970) and Frances (born 1973).

Fitzgerald's hobbies included tennis, music and reading; and he was a member of the Melbourne Club, Victorian Racing Club and Royal South Yarra Lawn Tennis Club.