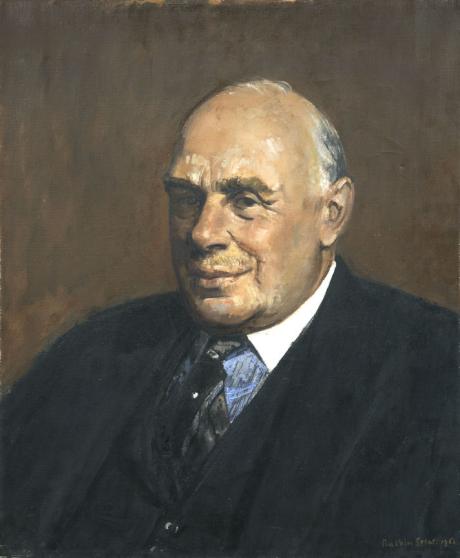

signed and dated "Ruskin Spear/1962"

Lyttelton, Oliver, first Viscount Chandos (1893–1972), businessman and politician, was born on 15 March 1893, the only son (another died in infancy) and elder child of Alfred Lyttelton (1857–1913), politician, and his second wife, Edith Sophy Lyttelton (1865–1948), daughter of Archibald Balfour. He was educated at Eton College (where his uncle Edward Lyttelton was headmaster) and Trinity College, Cambridge. His university career was cut short after just two years by the outbreak of the First World War. He immediately volunteered. Initially commissioned in the 4th battalion, Bedfordshire regiment, he was transferred to the Grenadier Guards, where he eventually rose to the rank of brigade major. He served in France continuously from early in 1915 to April 1918, when he was wounded in a gas attack. He was mentioned in dispatches on three occasions and won the DSO and the MC. Among the most important and enduring friendships he made during these years was that with Winston Churchill, whom he met in the trenches in 1915 after the latter had joined the guards in the wake of the Dardanelles disaster. Lyttelton returned to Britain in February 1919 and shortly afterwards joined the banking firm of Brown Shipley & Co. In January 1920 he married Lady Moira Godolphin Osborne (1891–1976), daughter of George Godolphin Osborne, tenth duke of Leeds, and his wife, Lady Katherine Frances Lambton. They had a daughter and three sons, one of whom, Julian, was killed on active service in October 1944. In August 1920 Lyttelton was invited to join the British Metal Corporation, a firm established at the instigation of the British government with the long-term strategic objective of undermining Germany's domination of the metal trade and making the British empire self-supporting in non-ferrous metals. After a brief apprenticeship Lyttelton served as general manager of the corporation and subsequently as managing director. He also became chairman of the London Tin Corporation and joined the boards of a number of foreign companies, including that of the German firm Metallgesellschaft. He became one of a small group of individuals who through their multiple, interlocking directorships, effectively controlled the global metal trade. With only slight exaggeration, Lyttelton once joked, ‘l'étain, c'est moi!’. On the outbreak of war in September 1939 he was appointed controller of non-ferrous metals. He set about exploiting his extensive network of personal contacts and his intimate knowledge of the mining industry in order to secure for Britain vital supplies of metals at highly advantageous rates. His unconventional methods caused some anxiety at the Treasury, but over the course of the war they saved Britain a substantial amount of money.

After becoming prime minister in May 1940, Churchill sought to bring his old friend into his administration. His first step was to attach Lyttelton to his defence office as supply co-ordinator. In the reshuffle announced early in October, Lyttelton became president of the Board of Trade. The prime minister encouraged him to find a parliamentary seat and gave him his enthusiastic backing. Lyttelton discovered, however, that an endorsement from Churchill was still regarded as a handicap by Conservative Party managers. The elevation to the Lords of the sitting member eventually freed the Aldershot division of Hampshire. Lyttelton held the seat from 1940 until 1954. One of his most important decisions while at the Board of Trade was to introduce clothes rationing. As he correctly predicted, this met with public support despite Churchill's warnings to the contrary. At the end of June 1941 Churchill sent Lyttelton to Cairo as minister of state and member of the war cabinet. He wished to relieve Britain's military commanders of some of the sensitive political and diplomatic problems raised by the conflict in the Middle Eastern theatre. These included liaison with General de Gaulle and the Free French, and the close supervision of Britain's client regimes in the region. Controversially, and against the initial advice of the military, Lyttelton accepted the view of the British ambassador in Cairo that the security of the British base in Egypt depended on the creation there of a government with greater public support. On 4 February 1942 British tanks surrounded the royal palace and King Farouk was obliged to appoint as his new prime minister the Wafdist leader Mustafa al-Nahhas. The spectacle of Britain using force to install the head of an avowedly anti-British movement in the name of greater democracy must have appealed to Lyttelton's sense of the absurd. At the end of February 1942 Lyttelton was recalled to London to succeed Lord Beaverbrook in the recently created post of minister of production. He paid particular attention to the vital task of co-ordinating production with the United States government. At the time of his appointment to the post, his standing among Conservative back-benchers was probably at its height. He was identified by Churchill—and by more objective observers—as a potential rival to Anthony Eden for the future leadership of the party. Yet although the challenge of power excited him, Lyttelton was not conventionally politically ambitious. He remained most at home in the City, and he tended to trust the judgements of fellow businessmen more than those of party politicians or civil servants. When presented as a minister with what he regarded as a particularly patronizing or obtuse piece of advice, he would sometimes reply with the stark minute ‘O.L., born 1893’. He certainly brought to his various ministerial posts valuable business acumen which few officials shared. It is difficult to believe, for example, that the government would have experienced the problems it did with the Colonial Development Corporation had Lyttelton entered the Colonial Office in 1945 rather than 1951. Yet he was sometimes unduly dismissive of the views of talented and astute subordinates. One of his principal recreations was poking fun at the pretensions of government and its agents. Lyttelton's sharp wit and talent for mimicry (inherited from his father) delighted his friends. Yet, although lacking real malice, his peculiarly black sense of humour struck some as cynical or even callous. His most serious political shortcoming, however, was his failure ever to master fully the art of parliamentary debate. A particularly poor performance responding for the government to John Wardlaw-Milne's motion of no confidence in July 1942 undoubtedly harmed his prospects for promotion.Lyttelton remained minister of production during Churchill's caretaker government of May to July 1945, combining this with his old job as president of the Board of Trade. After the Conservatives' defeat in the 1945 general election, he became chairman of Associated Electrical Industries (AEI). He retained his parliamentary seat and acted as a prominent member of Churchill's front-bench team. As chairman of the Conservative back-bench trade and industry committee, he led opposition in the Commons to the government's proposals to nationalize the steel industry. In 1950, with the death of Oliver Stanley, he became chairman of the party's finance committee. Churchill, however, pointedly refused to confirm that the chancellorship would automatically be his in any future Conservative administration. When the Conservatives were returned to power in October 1951, a number of factors persuaded Churchill to make R. A. Butler chancellor of the exchequer in preference to Lyttelton. Lyttelton's weakness in debate was an important one. Furthermore, Churchill was warned by Eden that Lyttelton's close association with the City was likely to antagonize the Labour opposition. Indeed, it was feared that Lyttelton's reputation as a ‘City shark’ (Butler's own phrase) might even undermine business confidence in the new government. Instead, after Lyttelton had expressed disappointment in the offer of the Ministry of Materials, Churchill sent him to the Colonial Office as secretary of state, a post that had been occupied by his father in Balfour's administration. Lyttelton carried unusual weight in cabinet for a colonial secretary, and he deployed this to considerable effect. His first priority was Malaya, where the recent assassination of the high commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney, had severely undermined British confidence in their ability to defeat a communist guerrilla movement. Lyttelton quickly recognized the need to combine the responsibilities of high commissioner and commander-in-chief. He selected Sir Gerald Templer for the task and provided him with the necessary authority both to undertake sweeping counter-insurgency measures and to promote rapid constitutional change. In October 1952 the newly appointed governor, Sir Evelyn Baring, declared a state of emergency, presenting Lyttelton with another major military operation to oversee. In its initial stages the British response to unrest in Kenya was poorly formulated and may actually have exacerbated the problem of armed resistance. Only with the appointment as commander-in-chief of General Sir George Erskine in June 1953 did the campaign against the Mau Mau begin to turn in the Kenya government's favour. Lyttelton had few qualms about the sometimes brutal measures employed against those identified as terrorist suspects or sympathizers. He regarded the increasingly vocal minority of Labour MPs who questioned this approach as at best sentimental and at worst disloyal. The evident embarrassment and division produced on the opposition benches by the government's decision in 1953 to remove Cheddi Jagan's radical administration in British Guiana caused Lyttelton some satisfaction. Yet the overall direction of British colonial policy underwent little significant change during his time as secretary of state. Shortly after assuming office, Lyttelton had, at the suggestion of his senior officials, publicly reaffirmed the government's commitment to leading the colonies to ‘self-government within the British Commonwealth’. He was prepared to pursue that policy not only in Malaya, where he was fairly optimistic about the long-term political prospects, but also in west Africa, where he decidedly was not. In February 1952 he recommended to his colleagues ‘with great reluctance but without any doubt or hesitation’, that the Gold Coast be granted the formal trappings of cabinet government, and that the colony's radical nationalist leader, Kwame Nkrumah, be given the title of prime minister (cabinet memorandum, 9 Feb 1952, C(52) 28, TNA: PRO CAB 129/49). At constitutional conferences in London in July and August 1953 and in Lagos in January 1954 Lyttelton constructed a new, federal constitution for Nigeria and prepared the ground for the achievement of internal self-government for Nigeria's eastern and western regions in 1956. In his Memoirs (published four years before Nigeria's collapse into civil war) he rated these negotiations the most successful of his time at the Colonial Office.

Lyttelton vigorously promoted plans, inherited from the Attlee government, for a federation of Northern and Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, a scheme that commanded the active support of his former colleagues in the mining industry and the almost overwhelming opposition of the African populations of the two northern territories. He was attracted by the notion that a similar federation might be attempted in east Africa. When, however, he publicly expressed tentative support for such a scheme in June 1953, he provoked a constitutional crisis. The traditional ruler of Uganda's largest and most important province, Edward Mutesa, kabaka of Buganda, used the widespread outrage over the suggestion as a pretext to defy the modernizing programme of Uganda's new governor, Sir Andrew Cohen, and to assert Buganda's autonomy. When the kabaka refused to co-operate, Cohen insisted that he be exiled to London and Lyttelton reluctantly agreed. In December 1953 Lyttelton warned Churchill that his various financial commitments would soon force him to seek more remunerative employment. He estimated that his ministerial salary represented an annual loss of some £10,000–12,000 on his potential earnings as a captain of industry. He wished to take up the chairmanship of his old firm, AEI, which was about to fall vacant. Fearing a further erosion of the Conservatives' slender parliamentary majority, Churchill summoned the directors of AEI to Downing Street and urged them not to press for Lyttelton's early resignation. Lyttelton was persuaded to remain at the Colonial Office until the end of July 1954. He was subsequently (9 September 1954) elevated to the House of Lords as Viscount Chandos. Chandos resumed his business career with the same energy and enthusiasm as before, although with considerably less success. He undertook an ambitious programme of expansion and development at AEI. Yet profits declined, and only four years after his retirement in 1963, the company was absorbed by its rival the General Electric Company. During his second term as chairman of AEI, Chandos also served as president of the Institute of Directors. In addition, he sat on the boards of ICI and Alliance Assurance Co. Ltd. His extra-political interests had always ranged far beyond the business world to embrace modern and classical literature and the performing arts. In retirement Chandos devoted a considerable amount of time to the National Theatre. He served as chairman of its board from 1962 to 1971, and then as president until the time of his death. This was something of a labour of love: his mother, to whom he was devoted, had long campaigned for the establishment of such a theatre. The Lyttelton Theatre, part of the National's complex of buildings opened on London's South Bank in 1976, serves as a fitting tribute to his efforts in this field. Yet he found himself increasingly out of sympathy with the prevailing artistic climate and, in particular, with the approach of the National's flamboyant literary manager, Kenneth Tynan. He came close to resignation from the board over plans to stage Rolf Hochhuth's play Soldiers, a work set during the Second World War, which both attacked Churchill over the saturation bombing of German cities and implied that the British secret service had been responsible for the death of Sikorski, head of the Polish government-in-exile. Chandos's elegantly written Memoirs appeared in 1962 to warm reviews, and they were followed six years later by From Peace to War: a Study in Contrast, 1857–1918. Chandos died in a London hospital on 21 January 1972. He was buried on 29 January in Hagley, Worcestershire, the Lytteltons' ancestral home. He was succeeded as second viscount by his eldest son, Anthony Alfred (1920–1980).

Philip Murphy DNB

Spear, (Augustus John) Ruskin (1911–1990), artist and teacher of art, was born on 30 June 1911 in Hammersmith, London, the only son and youngest of five children of Augustus Spear, coach builder and coach painter, and his wife, (Matilda) Jane Lemon, cook. He acquired his unusual and appropriate forenames by being named Augustus after his father, John after his maternal grandfather, and Ruskin after a member of the artistically inclined family with whom his mother was in service at the time of his birth. Disabled by polio at an early age, Spear attended the Brook Green School, Hammersmith, for afflicted children, where his artistic talent was recognized. He went on to study at the Hammersmith School of Art on a scholarship, aged about fifteen, and then at the Royal College of Art in London (1930–34), on another scholarship, under Sir William Rothenstein.

Spear subsidized his own work by teaching, stating that he ‘tried to believe money unimportant’, and he noted wryly: ‘first teaching appointment Croydon School of Art. Fee for 2½ hours, 16 shillings plus train fare. The Principal, interested in palmistry, read my hand, deciding it was promising, offered me four days per week’. He taught at Croydon, Sidcup, Bromley, St Martin's, Central, and Hammersmith schools of art, and—notably—as a visiting teacher in the painting school at the Royal College of Art (1952–77). He was also a gifted musician, and added to his income by playing jazz piano.

Throughout his life Spear regarded himself as ‘a working-class cockney’, while pursuing an extensive career as one of the liveliest members of the art world, loved by the public, fellow artists, and students, but only occasionally by the critics, by whom he was not taken seriously. He was a robust character, direct, colourful, pipe-smoking, and bearded. Known as a man with a prodigious thirst, he frequented his local pubs in Hammersmith and Chiswick, where his fellow drinkers formed a substantial proportion of his subject matter. He summed up his life view thus: ‘Painting, breathing, drinking, ars longa, vita brevis’. His polio caused a permanent limp and prevented active service in the Second World War. He did, however, contribute noteworthy paintings of working life on the home front, commissioned and purchased by the War Artists' Advisory Committee.

Spear became an associate of the Royal Academy in 1944 and Royal Academician in 1954. This enabled him as of right to contribute to the academy's summer exhibitions, where he had first exhibited in 1932. His facility with paint, and his fascination with low life and high life, and the foibles of both, often made his contributions newsworthy. Pub characters, members of the royal family, and politicians were his favourite subjects for academy presentation, with the portraits of public figures often based on newspaper photographs. He was a gentle satirist, exaggerating what was there rather than turning to stereotypes. He also portrayed ordinary life with vivid sympathy; a painting of a mother potting a baby caused the president of the Royal Academy, Sir Alfred Munnings, such displeasure in 1944 that it was not shown. In 1942 Spear was elected to the London Group, and was its president in 1949–50.

Spear had a thriving portrait practice among prominent figures. His subjects, which he proudly listed in his Who's Who entry, included lords Butler, Adrian, Olivier as Macbeth (painted from life), and Ramsey of Canterbury, Sir John Betjeman in a rowing boat, and lords Goodman and Howe of Aberavon. He was a portrayer of the human comedy with a light touch, in spite of often using a dark palette. He never had regular showings or a contract with a commercial gallery. He did occasionally exhibit abroad, but the only substantial exhibition of his work ever held in Britain (or anywhere) was the retrospective in the Diploma Galleries in the Royal Academy in 1980. The National Portrait Gallery has several of his portraits.

In spite of the relatively conventional, if exuberant, nature of his own work Spear promoted what he called the ‘modern chaps’, and was instrumental in turning the academy away from its unhealthy nostalgia; he was assisted by his outstanding success as a teacher during a golden age at the Royal College (Ron Kitaj, Frank Auerbach, David Hockney, and Peter Blake were his students). ‘We did a lot of teaching. The atmosphere tingled with the excitement of being free.’ Spear himself produced portraits endowed with sympathy; he was also a fascinating reporter, but his portrayals often appeared skin-deep rather than profound, and his talent was ‘made in England’ and not for travel. He was appointed CBE in 1979.

In 1935 Spear married (Hilda) Mary, artist and only child of William Henry Freer Hill, civil engineer, and Hilda Anne Grose; they had a son. The existence of his long-lasting liaison with Claire Stafford, an artist's model whom he met in 1956 when she was sixteen, was posthumously publicly revealed in 1993. They had a daughter, Rachel Spear-Stafford (b. 1957). Spear died in Hammersmith on 17 January 1990. A memorial service was held at St James's, Piccadilly, London, on 14 March 1990.

Marina Vaizey DNB