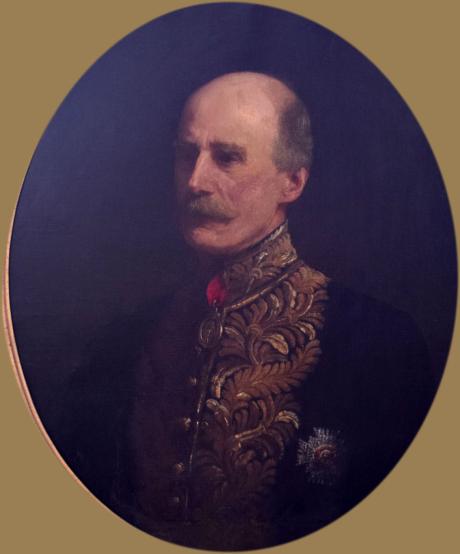

"C. Ouless. 1912" and further inscribed on a plaque attached to the frame " Presented by the / Exchequer and Audit Department / as a mark of their esteem and regard / June 1911

Reginald Baliol Brett, second Viscount Esher (1852–1930), courtier, was born on 30 June 1852 at 19 Prince's Terrace, Kensington, London, the eldest of three children of William Baliol Brett, first Viscount Esher (1815–1899), barrister and later master of the rolls, and his wife, Eugénie (1814–1904), a Frenchwoman, daughter of Louis Mayer and a stepdaughter of Colonel John Gurwood (1790–1845), the editor of Wellington's dispatches. The Bretts had been small squires, but they had no fixed estate. W. B. Brett acquired a moderate fortune at the bar, became a Conservative MP, solicitor-general, and in 1885 was ennobled by Lord Salisbury.

Esher remembered sitting on the lap of an old man who had played violin for Marie Antoinette, Reginald Brett went to preparatory school at Cheam in 1863 and to Eton College in 1865. His five years at Eton were among the most important in his life. The political and romantic friendships he developed there influenced his later career and personality. They rendered Eton a lost golden age that he looked back upon with longing, nostalgia, and regret. His most influential master there, William Johnson (1823–1892), encouraged adolescent homoeroticism and historical study of heroic statesmen. Later, in 1872, Johnson had to resign from Eton, reportedly because of a scandal with a boy. He changed his surname to Cory, married, and lived in retirement, but Brett remained loyal and later published a memoir of him, Ionicus (1923). William Johnson Cory, whose pupils included the future prime minister Lord Rosebery and others in the highest echelons of society. Rosebery's idealistic learning from romantic poets Wordsworth and Coleridge, the liberal philosopher J S Mill, the chemistry of Leibniz, music of Mozart, and Jeremy Bentham were intellectual influences on the young Regy.

Brett went to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1870 (BA 1875, MA 1879, hon. LLD 1914). He soon met William Harcourt, then a barrister and Cambridge law professor, but later a leading Liberal politician. Harcourt let Brett occupy his rooms at Trinity. Brett's father was a Conservative, but influenced by Harcourt and a new Cambridge friend, son of the queen's former private secretary, Albert Grey, Brett became a Liberal, though he was perhaps most attracted by the style of the aristocratic whigs. Brett was profoundly influenced by William Harcourt the radical lawyer, politician and Professor of International Law. Harcourt controlled Brett's rooms, and lifestyle at Oxford. Brett's father had introduced him to Albert Grey's Committee, but had a long-standing dispute with General Charles Grey, the Queen's Equerry. Brett was admitted to the Society of Apostles, dedicated to emergent philosophies of European atheism; their number included the aristocratic literati of liberalism Frank, Gerald and Eustace Balfour, Frederick and Arthur Myers, Hallam and Lionel Tennyson, Edmund Gurney, S H and J G Butcher. Brett experimented approaching conversion to High Mass from Cardinal Newman on Sundays in London. The Oxford Movement included historians, J Sedgwick and F M Maitland holding an equally profound sway over his youthful scholarship.He was admitted to the Middle Temple in April 1873 and called to the bar in 1881, but never practised as a lawyer.

Brett was seen with the Carlton Gardens set of Lady Granville, he was friend of the Clare brothers, introduced by the Earl de Grey. He visited Howick Park, and took law with Lord Brougham and Vaux. The famous lawyer's lectures coincided with Justice Brett's employment with Richard Cross, as a parliamentary re-drafter at the Home Office. Albert Grey introductions provided an invitation to the India Office and entrée to met Sir Bartle Frere, the colonial administrator. When Disraeli tried to enforce Anglicanism, in the Public Worship Bill, and was defeated, Brett wrote copious letters to Hartington, leader of the Liberals in the Commons. The consequences were to push Harcourt into the limelight as a leading Liberal in the Commons. But moderates tended to be dragged into sharing a religious position when the Disraelian tradition was threatening to split English liberalism. Brett visited the actor's daughter Lady Waldegrave at Strawberry Hill, and took deportment lessons from the Duchess of Manchester at Kimbolton, Hartington's private secretary, stamping his credentials as a rich aesthete. Regy was a socialite cultivating many friendships among both aristocratic and successful people. Early on a passion for tradition and imperial liberalism would frustrate the radical right.

Late in 1877, on Harcourt's advice, Lord Hartington appointed Brett one of his private secretaries, starting in January 1878, which put him at the centre of Liberal politics. Brett wrote well and Hartington frequently used him as a speechwriter in their seven years together. Brett was Liberal MP for Penryn and Falmouth from 1880 to 1885. In November 1885 he unsuccessfully contested Plymouth, and he never again stood for elective office. The House of Commons was not his milieu. A private life in which he continued to have romantic relations with other men made him wary of publicity and of prominent office all his life. Working behind the scenes and in roles he tailored for himself suited him best.

On 24 September 1879 Brett married in Winkfield church Eleanor (Nellie) Frances Weston Van de Weyer (d. 7 February 1940), third and youngest daughter of Sylvain Van de Weyer, the Belgian ambassador. They had two sons, two daughters, and a happy marriage, despite Brett's male friends, or perhaps because his wife acknowledged and welcomed them. The Van de Weyers were friends of the queen and the newly-weds' move in 1884 to Orchard Lea, near Windsor, strengthened the connection. Association with the royal family was to be the key to much of Brett's later political influence and power. Among his varied friends were A. J. Balfour, Major-General Charles George Gordon—whom he greatly admired and whose death in January 1885 much affected him—and W. T. Stead. In 1884 he was secretly involved, with ‘Jackie’ Fisher and H. O. Arnold-Forster, in Stead's ‘The Truth about the Navy’ campaign.

The Great Eastern Crisis had released Turkey from the threat of Russian invasion. But the success of the Midlothian Campaign had re-energized Gladstone's authority as rightful leader of his party; casting Hartington and Brett as marginalized jingoes. Six years later the Whigs would be pushed into the unionist camp. Brett needed his vanity satisfied but felt comfortable in neither party. He rose to become the mediator between Liberal factions, and was a leading light at the Liberal Round Table Conference in 1887.

Having been a Conservative as a young man, Brett began his political career in 1880, as Liberal Member of Parliament for Penryn and Falmouth. He was Parliamentary Private Secretary to Lord Hartington, when Secretary of State for War (1882–85) and once drove him to a Cabinet meeting on a sleigh through the snow.[2] However he elected to withdraw from public politics in 1885, after losing an election at Plymouth, in favour of a behind the scenes role. He was instrumental in the Jameson raid of 1895 vigorously defending the imperialist Cecil Rhodes.

In 1895, Lord Brett became Permanent Secretary to the Office of Works, where the Prince of Wales was impressed by his zeal and dedication to the elderly Queen Victoria.[2] A lift was built at Windsor Castle to get the elderly Queen upstairs in a redecorated palace. In Kensington Palace, Esher would push the Queen around in wheel chair so she could revisit her childhood. The devoted royal servant would work even more closely with Edward VII. Upon his father's death on 24 May 1899, he succeeded him as 2nd Viscount Esher.

During the Boer War Esher had to intervene in the row between Lansdowne and General Wolseley, the Commander-in-Chief, who tended to blame the politician for military failures. He would make the walk between palace and War Office to iron out problems. Into the political vacuum, Esher wrote the memos that became established civil service procedure. When the Elgin Commission was asked to report on the conduct of war, it was Esher who wrote it after the Khaki Election, and continued to act to influence both King and parliament. They met Admiral Fisher at Balmoral to discuss reform of Naval structures, which relied heavily on Fisher's complex web of relatives in senior posts.

In 1901, Lord Esher was appointed a deputy lieutenant of Berkshire and became Deputy Governor and Constable of Windsor Castle. He remained close to the royal family until his death. By the end of 1903 Esher was meeting or corresponding with King Edward VII every day. He lived at 'Orchard Lea', Winkfield on the edge of the Great Park. During this period, he helped edit Queen Victoria's papers, publishing a work called Correspondence of Queen Victoria (1907).

From 1903 Esher shunned office, but was a member of Lord Elgin's South African War Commission, which investigated Britain's near-failure in the Boer War. At this time he was writing to the King daily (and having three or four meetings a day with the King’s adviser Lord Knollys), informing him of the views of the Commission, of party leaders, and War Office civil servants with whom he was still in touch from his days working for Hartington. St John Brodrick, Secretary of State for War, was resentful of Esher’s influence. Brodrick's scope for operation was paralysed by Esher's circumvention, and the government was much weakened in October 1903 when Joseph Chamberlain and Devonshire resigned over the former's plans for Tariff Reform.

After his parliamentary defeat in 1885 Brett resigned his post with Hartington. In the next ten years he wrote Footprints of Statesmen during the Eighteenth Century in Britain (1892) and The Yoke of Empire, Sketches of the Queen's Prime Ministers (1896). He raced horses, entertained, and decorated his house. None of this was enough to satisfy his ambitions. When his Eton contemporary Lord Rosebery became prime minister in 1894 and offered him the permanent secretaryship of the office of works in 1895, Brett accepted.

The office of works was responsible for maintenance and decoration of state buildings, including royal palaces. Brett had installed a lift for Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. He accompanied her to Kensington Palace and pushed her wheelchair around the rooms she had inhabited as a child. He also cultivated the prince of Wales, who asked him to serve on the committee to organize the diamond jubilee. Brett loved the theatre. He also agreed with Joseph Chamberlain's aim of closer imperial economic and defence unity. Under Brett's influence the diamond jubilee of 1897 was showier, more triumphal, and more imperial than previous London ceremonies. The jubilee organizers also persuaded the queen to drive south of the river through Kennington. They were attempting to bring the monarchy into closer contact with both the empire abroad and the newly enfranchised working classes at home.

When the queen died in January 1901 Lord Esher, as Brett became on his father's death in May 1899, was the one to whom others turned for precedents for her funeral. He also played a prominent part on the committee which planned Edward VII's coronation, and on another which created a memorial to Queen Victoria by reconstructing the Mall as a processional route from Admiralty Arch to the statuary group in front of Buckingham Palace. These efforts led the monarchy to acquire a new reputation for ceremonial.

Esher also promoted the monarchy's role in politics. Edward VII gave him rooms at Windsor Castle and superintendence of the archives. He used these, and his friendship with the king's private secretary Francis Knollys, to inform and advise the king. He provided examples from Queen Victoria's papers to show that the sovereign had been better informed in the previous reign and to advocate that ministers submit more official business to the king for review.

Closely connected was Esher's editing of the queen's letters in collaboration with A. C. Benson. The first three volumes, The Letters of Queen Victoria, 1837–1861, were published in 1907. Another six volumes were edited by G. E. Buckle, on Esher's lines. Esher intended the Letters to show that the queen had been well informed and influenced policy. He also wanted to reveal the queen's character, to put her in a heroic light, and to make the Letters widely accessible. The Letters were a work of selection and were meant as a monument to her. He also edited two volumes on her youth, The Girlhood of Queen Victoria (1912), and published an essay on Edward VII after his death in 1910. He retained close links to George V and his private secretary, Lord Stamfordham, though of the sovereigns he served he was closest to Edward. He was appointed constable and governor of Windsor Castle in 1928, posts then normally reserved for royalty. Although formerly a Liberal, and from 1886 a Liberal Unionist, he was essentially a conservative who wanted the monarch to retain influence in an increasingly democratic constitution; however, he remained friendly with Liberals, especially Rosebery and John Morley. Although he increased the prestige of the monarchy's ceremonial and helped retain the monarch's right to be informed, he could not prevent the continued dwindling of the monarchy's political influence.

From his Eton schooldays Esher was interested in military history, and as private secretary to Hartington when secretary of state for war and chairman of the Hartington commission (1888–1890) he became concerned with defence reform. The commission recommended War Office reorganization with a board approximately on the Admiralty model, abolition of the commander-in-chief, and a general staff: these were not implemented. However, in the early years of the twentieth century the situation became favourable for Esher and the reforms he wanted, essentially those of the Hartington commission. Edward VII, to whom he was confidant and adviser, became king; his friend Balfour became prime minister; and the South African War created a strong public and parliamentary demand for army reform. In November 1900 St John Brodrick (later earl of Midleton; 1856–1942) became secretary for war and Esher offered himself as permanent under-secretary at the War Office, hoping to influence policy. Brodrick refused, and thereafter opposed Esher's interference, including his attempts to have Roberts sacked from the command-in-chief. Later in his memoirs Brodrick wrote that Esher had 'power without responsibility' and that this 'usurpation of power by an outsider' caused 'endless contretemps' (Brodrick, 157, 149–50).

Esher was a member of the royal commission on the war in South Africa (the Elgin commission, 1902). Its report (1903) made no substantive reform recommendations but Esher dissented, advocating a War Office board. In September 1903 Balfour invited Esher to be war secretary, but he refused. He wrote to his son that he did not want to 'sacrifice all independence, all liberty of action … for a position which adds nothing to that which I now occupy' (Hamer, 224). Balfour appointed H. O. Arnold-Forster (1855–1909). He proposed major army reorganization, which provoked strong opposition and against which Esher intrigued. Arnold-Forster condemned Esher's 'constant interference' by 'an unauthorised and irresponsible person' (ibid., 226), blamed him for the rejection of the proposals, and never forgave him. Meanwhile, in 1903 at Esher's suggestion, Balfour appointed the War Office reconstitution committee (the Esher committee): Esher (chairman), Sir John Fisher, and Sir George Sydenham Clarke, 'all being root-and-branch reformers' (Clarke, 175). Its reports (1904) proposed radical War Office reorganization: abolition of the commander-in-chief and establishment of an army board and general staff. It also recommended a permanent secretariat for the committee of imperial defence (CID). Moreover the Esher committee insisted that 'new practices demand new men' (ibid., 236) and that the ‘old gang’ of Roberts and others must be replaced. Balfour rapidly implemented the War Office reform, and new men, mostly those favoured by Esher and his colleagues, were appointed. The War Office reform was crucial, introducing 'a functional structure designed to prepare the army for war' (Gooch, Boer war, 47). From 1905 Esher was a permanent member of the CID.

From 1905 to 1912 R. B. Haldane was secretary for war. Esher became his confidant and adviser, chaired his unofficial Territorial Army committee (1906)—nicknamed the Duma—and supported his reforms. Esher believed compulsory service ultimately necessary but politically unfeasible until the Territorial Force (TF) had been tried. He supported the TF and was chairman (1909–13) and later president (1912–21) of the London County Territorial Force Association. On the CID and its subcommittees he had an active role in defence planning. In 1909, for example, he unsuccessfully proposed, contrary to the rival War Office and Admiralty strategies for possible war with Germany, a strategy of naval blockades and raids, with a token land force to assist the French.

During the First World War, Esher served in France liaising informally between French and British generals. He spoke excellent French and perhaps because his mother was French he understood the French better than most. He also reported to his cabinet and court friends on the problems of the British staff officers. His role was not well defined and inspired the jealousy of the British ambassador. There had been similar protests in the newspapers about his ‘irresponsible’ influence before the war. While some distrusted him, others confided in him as a useful conduit to those in high office. Kitchener, Haig, Asquith, Balfour, Stamfordham, and George V regarded him as contributing to the war effort.

After the war Esher and his wife spent much time in Scotland. Although his parents had lived relatively modestly in London and at a small country place Esher used his paternal inheritance, about £130,000, to acquire houses in Mayfair, Windsor, and Perthshire. He also profited from his brief association (1901–4) with the City financier Ernest Cassel. Cassel was a crony of Edward VII who hired Esher to look after his interests in Egypt and America at a salary of £5000 a year and 10 per cent of the firm's profits.

Behind the scenes, he influenced many pre-First World War military reforms and was a supporter of the British–French Entente Cordiale. He chaired the War Office Reconstitution Committee. This recommended radical reform of the British Army, including the setting up of the Army Council, and established the Committee of Imperial Defence, a permanent secretariat that Esher joined in 1905. From 1904 all War Office appointments were approved and often suggested by Esher. He approved the setting up of the Territorial Force, although he saw it as a step towards conscription; a step not taken. Many of Esher’s recommendations were nonetheless, implemented under the new Liberal governments of Henry Campbell-Bannerman and H. H. Asquith by Haldane, Secretary of State for War, assisted by Esher's protege the young Major-General Douglas Haig. When Haldane entered the War Office, he was provided with Colonel Sir Gerard Ellison as a new military secretary to make the transitional reforms. Haldane wished to avoid 'corner cuts' and so established the Information Bureau in the War Office. Although Eshers's biographer Peter Fraser argued "the Haldane reforms owed little to Haldane." The initial Liberal reforms were thrown out by the Lords, and the resulting documents looked like Esher's original efforts.

Esher found his son, Oliver Brett, a job as an additional secretary to John Morley and he was on good terms with Capt Sinclair, Campbell-Bannerman's secretary.

Esher was appointed a Deputy Lieutenant of the County of London in 1909. and the King's Aide-de-Camp. Depicted as a disciple of national efficiency, an able administrator, and a silky, smooth influence as a courtier, he was accused of being an arch-insider, undemocratcic and interfering. Moreover, the King liked Esher, and so his influence over the Army grew, leading to a more liberal far-sighted attitude towards the possibility of averting conflict in Europe. Esher's invaluable contribution prevented further promotion in a political career, in which he had been destined for high cabinet office. His close political friends in the Liberal party included Edward Marjoribanks and Earl Rosebery. His aristocratic connections and military experience made him an ideal grandee, but such was the importance of his ties to the monarch, that his career was somewhat restrictive of ambition. He was by nature ambitious, 'clubbable' sociable, and frequently seen at High Society parties in the fashionable houses of the Edwardian era. He was secretive and patriotic: accordingly founding the Society of Islanders. Its one great principle was to build "two for one Keels" over and above any other Navy in the world in order to maintain global peace.

In 1911 Esher helped ease out Lord Knollys, who was then seventy-five years old, having been in the Royal Household since 1862, but who had lost some royal confidence over the negotiation of the Parliament Act. Esher arranged a replacement as King George V's principal adviser with Lord Stamfordham.

Esher declined many public offices, including the Viceroyalty of India and the Secretaryship for War, a job to which King Edward VII had urged he be appointed.

Esher's involvements in the Territorial Army were not limited to the War Office. He was the first chairman appointed in 1908 to the County of London Territorial Forces Association and its president from 1912 to his death, in addition he was appointed honorary colonel of the 5th (Reserve) Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers in 1908 and held the same appointment with the 63rd (London) Brigade of the Royal Field Artillery from 1910 to 1921.

In January 1915, Esher visited Premier Briand in Paris, who told him Lloyd George had "a longer view than any of our leaders". An earlier opening of a Salonika Front might have prevented the entry of Bulgaria into the war". He also made contact with Bunau Varilla, editor of Le Matin, to keep Russia in "the alliance and Americans to come to aid of Europe". By 1916 the French war effort was almost spent. Finance Minister, Alexandre Ribot told them to sue for peace, Esher reported. At the Chantilly Conference they discussed combined operations - "Dans la guerre l'inertie est une honte."[clarification needed Esher accompanied Sir Douglas Haig to the Amiens Conference, but was back in Paris to be informed of the surprise news of Kitchener's death. Returning to London Esher spoke with Billy Hughes, Prime Minister of Australia. The following month at the Beaugency Conference they discussed the Somme Offensive. "For heaven's sake put every ounce you have got of will power into this offensive" he told Hankey. He often travelled to France to leave the "mephitic" atmosphere of the War Office, on a trip to Liaison Officer, Colonel Sidney Clive at Chantilly. He learnt first hand the French government's scheme for a "Greater Syria" to include British controlled Palestine. France's ally on the Eastern Front, Russia, had been badly defeated the previous year; so Asquith's neutrality over Briand's Salonika Plan perplexed Esher. He perceived the balance of power in cabinet shifting towards a new more conservative coalition.

During the First World War Esher was, in one writer’s description, de facto head of British Intelligence in France, reporting on the French domestic and political situation, although he told his son he preferred not to have a formal position where he would have to take orders. His son Maurice Brett set up a bureau in Paris called Intelligence Anglaise keeping his father informed through a small spy network with links to newspaper journalists.

In 1917 he told Lloyd George that the diplomacy in Paris was weak, informing the Prime Minister that he "was badly served". The ambassador Lord Bertie was the last of the Victorian imperial envoys, and was failing to do enough to persuade a faltering France to remain fighting in the war. When offered the ambassadorship in Bertie's stead Esher crowed "I cannot imagine anything I would detest more." His considerable diplomatic skills included fluent French and German. The following month there was a French mutiny, as the Poilus were dying in appalling conditions. Haig and Wilson lent their support to an offensive to bolster the French. Petain, the new French commander-in-chief, was deemed too defensive: Esher sent Colonel Repington as liaison officer on a 'charm offensive'. Backed by Churchill and Milner for dramatic action, Esher entered a diplomatic conversation with the Cabinet's War Policy Committee; a unique new departure in the management of British policy. The bad weather and sickness of war made Esher ill in 1917; he was encouraged by the King to holiday at Biarritz.

Partly on Esher's advice, the War Office undertook major re-organization in 1917. He advised unification of commands, in which all British military commands would be controlled from Whitehall's Imperial War Office only. Esher was at the famous Crillon Club dinner meeting in Paris on 1 December 1917 in which with Clemenceau they took critical decisions over the strategy for 1918. The Allied Governments proposed a unified Allied Reserve, despite negative press and publicity in the Commons. As cabinet enforcer, Esher visited Henry Wilson on 9 February 1918, during the crisis over his succession to Robertson as CIGS. Esher became instrumental in remonstrating with loose press articles critical of the war effort in particular, the Northcliffe press and the Morning Post, which was seized and shut down at 6.30 pm on Tuesday, 10 February 1918. In France, Esher had established a rapprochement with the press to help hold the Poincare-Clemenceau government together, at a time when England was at the zenith of her military strength."

Esher was admitted to the Privy Council in 1922. In 1928 he became Constable and Governor of Windsor Castle, an office he had always wanted, holding it until his death in 1930.

In retirement Esher's activities were mainly literary. He had already published compilations of his journalism: Today and Tomorrow (1910) and The Influence of King Edward (1914). He published After the War (1918), a slim volume dedicated to Robert Smillie (1857–1940), the trade union leader, which argued against too radical reform of institutions, like the crown, of which leftist politicians were critical. He also wrote The Tragedy of Lord Kitchener (1921), describing Kitchener's flaws; some reviewers alleged that it was unfair and disloyal. In his autobiographical essays, Cloud Capp'd Towers (1927), Esher criticized Lytton Strachey and others for mocking the Victorians. At the end of his life he declared himself out of sympathy with the temper of the times. Lord Esher was also a historian; besides the aforementioned work, he also published works on King Edward VII and Lord Kitchener. Together with Liberal MP Lewis ("Loulou") Harcourt he established the London Museum, which opened its doors on 5 March 1912. In February 1920 he proof read Haig's History of the General Head Quarters 1917-1918. That summer Esher's critique of a Life of Disraeli appeared in Quarterly Review. His own life would be written by Oliver, eldest son and heir.

As the Great War concluded Esher intimated that the King wanted his resignation as Lieutenant-Governor of Windsor. In fact he coveted the post of Keeper of the Royal Archives. Stamfordham demanded his resignation in favour of historian Sir John Fortescue, but Esher remained as Governor. Professionalization also warned Hankey against becoming secretary to the Peace Conference, which to Esher's mind was beyond his competence. Esher also persuaded his friend not to desert the Empire for the League of Nations. Domestic unrest and trade unionism, which Esher loathed, as it threatened peace and stability, also destabilized his position as President of the Army of India Committee. Ever skeptical of political changes, "omnivorous" introductions to the Viceroy's work forced him to decline a solicitous offer to chair a sub-committee of the Conditions of the Poor.

Although on good terms with his wife at the end of his life, Esher did not have affectionate relationships with three of his four children. Neither Oliver (later third Lord Esher) nor Sylvia, who married the future raja of Sarawak, nor Dorothy Brett, a painter who moved to New Mexico, felt they had been fairly treated by their father. Esher was unusually close to Maurice, his second son, with whom he had a passionate relationship, especially while the boy was at Eton. In later life Maurice bore his father no grudge, married actress Zena Dare, and began editing his father's papers; after Maurice's death Oliver completed the project.

Esher died in the dressing room of his London house, 2 Tilney Street, Mayfair, on 22 January 1930 while preparing to meet a male protégé for lunch at Brooks's. He was buried in the family vault in the graveyard of the Esher parish church. He was succeeded by his elder son, Oliver Sylvain Baliol Brett (1881–1963).

Esher was intelligent, able, and arrogant, with a gift for friendship; an effective and adaptable organizer, negotiator, intermediary, and manipulator. He was an enigma to contemporaries and has puzzled historians. A controversial éminence grise, functioning largely behind closed doors and through others, his own achievement is difficult to assess. Edward VII liked and relied on Esher. As a result, Esher aroused the contempt and suspicion traditionally felt for courtiers and royal favourites. Some distrusted him as an irresponsible, devious intriguer who plotted, leaked confidential information, and interfered unconstitutionally in affairs of state. Some persons also distrusted his financial role and associates. Sir Charles Brooke, the raja of Sarawak, opposed the marriage of his heir, Vyner, to Esher's daughter Sylvia because he suspected a plutocratic plot, involving Esher, to exploit Sarawak. However, although Esher did not originate the defence reforms, his role in defence reform and planning contributed to British preparedness in 1914 and victory in 1918. Moreover the monarchy's success as a national and imperial symbol was partly due to his stage-management of its most prominent ceremonies. Esher's most cheerful experiences were at Roman Camp in Callander, Scotland. He embraced the healthy Scottish highland air. His son, Maurice Brett was the successful founder of MI6 in Esher's Paris flat during the war; a meeting place for Prime Ministers and Presidents. In November 1919, Maurice sold Orchard Lea; Esher was a family man.

Astute, reserved, and modestly discreet Esher assiduously courted success and avoided scandal. He turned down an invitation to attend on David, Prince of Wales and his mistress Freda Dudley Ward at Balmoral. But when his wild, artistic daughter invited Colette and husband Bunau Varilla, the family stayed on his yacht in the Clyde; family came first. Dorothy Brett was a slightly bohemian artist living at 2 Tilney Street. She befriended Gertler, a wild Russian Jew, her father despaired.

KCB : Knight Commander the Order of the Bath – announced in the 1902 Coronation Honours list on 26 June 1902 – invested by King Edward while on board his yacht HMY Victoria and Albert on 28 July 1902 (gazetted 11 July 1902)

GCVO: Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (previously KCVO)

In 1879, Reginald Brett married Eleanor Van de Weyer, daughter of Belgian ambassador Sylvain Van de Weyer and granddaughter of Anglo-American financier Joshua Bates. They had four children.

Their elder son, Oliver Sylvain Baliol Brett became 3rd Viscount Esher and was a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects. He married Antoinette Heckscher, daughter of August Heckscher.

Their second son, Maurice Vyner Baliol Brett, married the famous musical theatre actress Zena Dare.

Their older daughter, Dorothy, was a painter and member of the Bloomsbury Group. She studied at the Slade School of Fine Arts and spent years in New Mexico.

Their younger daughter, Sylvia, became the last Ranee of Sarawak on 24 May 1917, following the proclamation of her husband Charles Vyner Brooke as Rajah.

Daughter of Walter William Ouless Rahe attended the RA Schools as a student from 25 July 1899 to July 1904. Painter. Landscapes, portraits, scenes with figures. She exhibited four pieces of work at the Royal Academy during the short time she lived in London. Although an occasional portraitist, Catherine usually painted landscapes. She painted a number of notebale sitters including ; George V, Andrew Carnegie, 1835 – 1919. the Ironmaster and philanthropist, Ernest Ruthven Sykes (1868–1954),Esther Burrows, Principal (1893–1910), Charles Cave Cave of Deepdale.