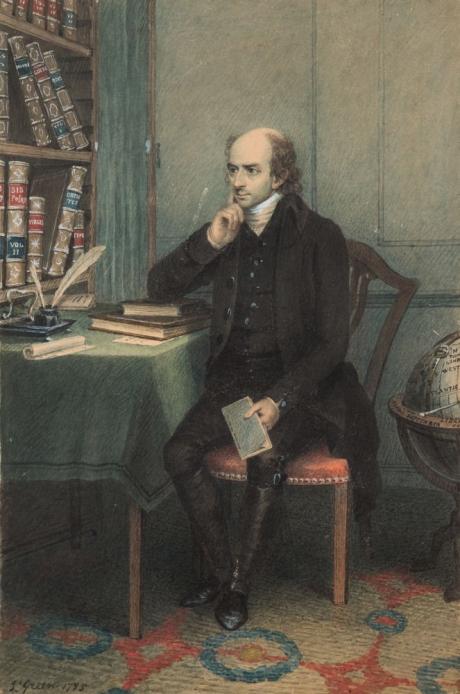

"J Green 1795"

Gilbert Wakefield, (1756–1801), biblical scholar and religious controversialist, born on 22 February 1756 in the parsonage-house of St Nicholas's, Nottingham, was the third son of George Wakefield (1720–1776), rector of that parish and later vicar of Richmond and Kingston, and his wife, Elizabeth (1721–1800), whose grandfather had been twice mayor of Nottingham. From infancy, Wakefield showed a remarkable aptitude for learning, but his early education was erratic: passed from master to master, he made considerable progress after enrolling at the free school of Kingston in 1770. There he was among the last to study with Richard Wooddeson, who had counted George Steevens, Edward Gibbon, and William Hayley among his scholars.

In April 1772 Wakefield entered Jesus College, Cambridge, having obtained a Marsden scholarship, established ‘for the son of a living clergyman, born at Nottingham, both of which conditions were united in me’ (Memoirs of the Life, 1.62). As was customary, he divided his studies between mathematics and classics, preferring the latter, but applying himself to the former ‘with all the assiduity that I could bear’ (ibid., 1.83). When not engaged in formal study, he taught himself Hebrew, played cricket and fished, published a volume of Latin verse (1776), and befriended Robert Tyrwhitt and John Jebb (who also inclined to Unitarian views). He received his BA in January 1776, second wrangler and second chancellor medallist in classics. In April of that year he was elected fellow of his college.

Wakefield spent the years of his fellowship dedicated to biblical studies, acquiring several oriental languages as he did so. In 1778 he was ordained deacon, in spite of growing doubts about matters of doctrine and scruples about the practice of subscription to the Thirty-Nine Articles (several Jesuans, including Tyrwhitt, had recently resigned their fellowships over this practice). It was, he later wrote, ‘the most disingenuous action of my whole life; utterly incapable of palliation or apology’ (Memoirs of the Life, 1.121). His clerical life lasted just over a year: he served as curate in Stockport, Cheshire, under a Mr Watson, then successively at St Peter's and St Paul's in Liverpool, all the while hoping to find employment as a schoolmaster. In Liverpool he crusaded against the slave trade and British privateering, and denounced both practices from the pulpit, angering many parishioners. This was the first sign of the political activism that was to characterize his later life.

On 23 March 1779 Wakefield married Anne Watson (d. 1819), the niece of his rector in Stockport. The couple had five sons and two daughters. Wakefield gave up his fellowship on marrying, and shortly afterwards he resigned his curacy as well because of doctrinal differences. Wakefield's study of scripture had led him to reject the doctrines of the Trinity and incarnation. Yet he embraced the teachings of Jesus Christ, whom he regarded as the greatest moral philosopher, sent by God to redeem mankind. Chief among these teachings was the mandate to love one another, and the corollary to it was service to the poor, respect for individual liberty, and the pursuit of peace. Initially he was opposed to all but defensive war, and later became a total pacifist. Although technically a dissenter or Unitarian, Wakefield never associated himself with any sect or congregation, being averse to most forms of worship.

In the summer of 1779 Wakefield accepted an appointment as classical tutor at Warrington Academy, the prominent dissenting academy where Joseph Priestley had taught, and where John Aikin was tutor of divinity and William Enfield tutor of philosophy. The years at Warrington were the happiest of his life. There he began a lifelong friendship with the Aikin family (his beloved daughter Anne later married Charles Aikin), established valuable connections with wealthy dissenters, and was encouraged to pursue his theological enquiries. These began to appear, in pamphlet form, in 1781. Essays on baptism and inspiration gained him notoriety as a controversialist, while his New Translation of the First Epistle of Paul to the Thessalonians (1781) announced his intention to produce a new translation of the New Testament, a project completed a decade later. The following year saw the publication of his first book-length work, A new translation of the gospel of St Matthew, with notes critical, philological, and explanatory (1782). This work aimed to follow the idiom and phraseology of the original as closely as possible, and to apply the principles of classical philology to study of the Bible. It is an interesting early example of historical criticism, but Wakefield's denunciations of Anglican doctrine and the American War of Independence made even his friends uncomfortable, and made him the object of ridicule in the periodical press. When Warrington Academy failed in 1783, Wakefield's outspokenness was thought to have been a partial cause; the next year, when his Enquiry into the opinions of the Christian writers of the three first centuries concerning the person of Jesus Christ (1784) sold poorly, he ceased publication on theological subjects for several years.

After leaving Warrington in 1783, Wakefield resided briefly at Bramcote, near Nottingham, and at Richmond, in Surrey, before settling in Nottingham in 1784, where he ‘had three or four pupils on very handsome terms’ (Memoirs of the Life, 1.270). Over the next two years, a pain in the left shoulder ‘harasst me beyond measure’ (ibid., 277) so that he lost all but one of his pupils and was able to write little: an edition of the poetry of Thomas Gray appeared in 1786, and of Virgil's Georgics, published by Cambridge University Press, in 1788. Cambridge also published his Silva critica, the first volume of which appeared in 1789. The Silva, one of Wakefield's most important works, was intended to demonstrate ‘the union of theological and classical learning … thus promoting in the world at the same time a profitable heathenism … and a rational theology’ (ibid., 1.293). Unlike his earlier theological works, the Silva was well received in both Anglican and dissenting circles; it was completed in five volumes in 1795.

A new dissenting college had been established in 1786, eventually located at Hackney, and its founders, including the radical minister Richard Price, invited Wakefield to become classical tutor. He accepted, moving to Hackney in 1790. The appointment was not without controversy: Price and Priestley were initially opposed, ostensibly because of Wakefield's refusal to attend Christian worship. Wakefield himself was hesitant because he felt that the college's requirements in classical philology were insufficient for understanding scripture. A year later he resigned, defending himself in An Enquiry into the Expediency and Propriety of Public or Social Worship, where he argued that there was no gospel authority for public worship. This pamphlet was satirized in the Pittite press and sparked a public debate among liberal dissenters, to which Priestley, Anna Barbauld, and Mary Hays all contributed. Wakefield's Memoirs (1792) was a product of this debate, designed as an apologia for his opinions and actions.

After resigning from Hackney College, Wakefield could no longer support himself as a private tutor, and began publishing at an astonishing rate. His translation of the New Testament was published in 1792 and went through several editions, including one in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Evidences of Christianity, a work of apologetics, appeared the next year. Companion editions of Horace (1794) and Virgil (1796), an edition, with extensive commentary, of selected Greek tragedies (2 vols., 1794), an edition of Moschus and Bion (1795), an annotated edition of Alexander Pope's Homer (12 vols., 1796), and, finally, his massive three-volume edition of Lucretius (1796–7), published at his own expense and dedicated to Charles James Fox, established Wakefield as one of the two leading British scholars of his time, the other being Richard Porson. Unlike Porson, however, Wakefield was excessively fond of emendation, always worked in great haste, and rarely took time for revision. Thus, although his critical remarks can show considerable brilliance and an unusual awareness of continental advances in scholarship (Wakefield seems to have been among the first Englishmen to promulgate F. A. Wolf's conclusions about Homer), his work is riddled with errors and was largely dismissed by the British Academy within a few years of his death.

Wakefield also achieved notoriety as a political controversialist for his attacks on the Pitt government. He had come to believe that true Christian morality and Pittite policy were wholly incompatible, and that any church promoting such policy was the Antichrist. In the French Revolution, wrote John Aikin, the son of his colleague at Warrington, Wakefield saw ‘the undoubted commencement of a better order of things, in which rational liberty, equitable policy, and pure religion, would finally become triumphant’ (Aikin, 1.208), and was appalled by British attempts to subvert its progress. Of the several pamphlets he wrote on this subject, most notable were The Spirit of Christianity Compared with the Spirit of the Times in Great Britain (1794), which influenced S. T. Coleridge, and A Reply to the Letter of Edmund Burke, Esq., to a Noble Lord (1796), both of which went through three editions. But Wakefield could be as vehement against Tom Paine as against Burke, and in two pamphlets (1794 and 1796) attacked the deism of The Age of Reason with such spirit that Pittite reviewers had to blink in wonder. These pamphlets circulated internationally, especially in America. Wakefield further incurred the displeasure of the government by organizing contributions for the defendants in the treason trials of 1794, and by defending William Frend against the charges brought against him by Cambridge University for publishing the pamphlet Peace and Union. Wakefield's defence of Frend caused the university press to withdraw support from the Silva critica, and its last two volumes were published in London at Tyrwhitt's expense.

By 1798 the prime minister, William Pitt (1759–1806), fearing a French invasion, had decided to silence political opposition, and Wakefield unluckily provided the occasion. In January of that year Richard Watson, bishop of Llandaff, published An Address to the People of Great Britain, supporting Pitt's proposal for an income tax. Wakefield responded in A Reply to some Parts of the Bishop of Landaff's Address, a pamphlet ‘never written over twice, and … finished … in the compass of a single day’ (Memoirs of the Life, 2.117). In it, he argued that the government had provoked war with France, and that this policy had so hurt the British poor that, if the French were to invade, they would be unlikely to meet with resistance.

For alas! the ground-floor of this grand and stable edifice, where myself, and my mess-mates of the swinish multitude, were regaling ourselves, as well as existing circumstances would possibly admit, on our cheese-parings and candles' ends; our ground-floor, I say, is sunk for ever in damps and darkness; only to make, forsooth! a more firm foundation for our aristocratical and prelatical superiors. (Reply to the Bishop of Landaff's Address, 16)

For this pamphlet Wakefield, together with his publisher and booksellers (including Joseph Johnson), were indicted on an information and convicted. Their convictions, thought Charles James Fox, meant that liberty of the press was dead. At the trial Wakefield eschewed the offer of legal assistance from the radical Scottish lawyer Henry Erskine (1746–1817) and represented his own case, casting himself as a latter-day Socrates or Jesus. Henry Crabb Robinson, who witnessed the event, wrote that ‘his delivery of his own defence must have been one of the most gratifying treats which a person of taste or sensibility could enjoy. His simplicity quite apostolic, his courage purely heroic’ (Henry Crabb Robinson, 1.36–7). Upon conviction, Wakefield was sentenced to two years' confinement in Dorchester gaol and a fine of £500. A fund was established to support his family, and £5000 was raised almost immediately, largely from Foxite whigs and liberal dissenters. Wakefield, who was never rich, remarked that he owed his fortune to his majesty's attorney-general (Memoirs of the Life, 2.156).

In prison, Wakefield became a celebrity among the politically disaffected. Fox, the duke of Bedford, and Lord Holland all visited him in his cell and took measures to ease his conditions. The friendship with Fox was especially rewarding, as the two had corresponded for several years, chiefly about classical literature. Wakefield led Fox to a new discovery about the dating of Lycophron, explained and defended his theories about the Homeric poems, and chided Fox gently about the evils of hunting and the virtues of vegetarianism. But, despite celebrity, the prison years were disheartening: in the first year Wakefield's mother died; in the second he suffered a recurrence of the debilitating shoulder ailment, spent much of his time attending to capital prisoners, and, just before his release, lost his youngest child to illness. Although he completed a translation of essays by Dio Chrysostom (1800), and a short work on Greek metres (Noctes carceriana, 1801), his main project, a Greek-English dictionary, was abandoned for lack of public interest, and a scholarly controversy with Porson grew increasingly mean-spirited.

Wakefield was released from prison on 29 May 1801 and returned to Hackney. It was at this time that William Artaud painted a large oil portrait of him, later housed at Dr Williams's Library, London. It shows a keen-eyed scholar at work in his study, a pamphlet open on the desk before him, the large folios of his Lucretius in the shadows. Wakefield barely lived to see the finished work: in late August he showed the first signs of typhus fever, and by 1 September was delirious. He died on 9 September 1801 at Hackney, in the company of family and close friends, having refused all medical assistance. Survivors included his wife and five of his children. The body was borne with great ceremony through the streets of London and interred on 18 September at St Mary Magdalene's, Richmond, where his brother, Thomas, was vicar. A tablet to Wakefield's memory hangs on the south wall of the church, erected by his brother. He was memorialized in prose by John Aikin, and in Latin and English elegies by Lucy Aikin, George Dyer, and Alexander Geddes. Three years later J. T. Rutt and A. Wainewright issued their two-volume Memoirs of Wakefield, which remains the standard account of his life.

Bruce E. Graver DNB

James Green, (1771–1834), portrait painter, was born at Leytonstone in Essex on 13 March 1771, the son of John Green, builder, and his wife, Sarah. He was apprenticed to Thomas Martyn, a draughtsman of natural history, who resided at 10 Great Marlborough Street, London. When his apprenticeship expired, he entered the Royal Academy Schools in 1791, where he attracted the notice of Sir Joshua Reynolds, and copied many of his pictures. In 1793 he exhibited at the Royal Academy several views of Tunbridge Wells, and some portraits. On 13 February 1805 Green married at St Marylebone, Marylebone Road, Marylebone, Middlesex, Mary Byrne [Mary Green (1776–1845)], second daughter of William Byrne (1743–1805) [see under Byrne family (per. 1765–1849)], the landscape engraver. She was a pupil of (L. A.?) Arlaud, and was a well-known miniature painter, exhibiting at the Royal Academy, the British Institution, and the Society of British Artists from 1795 to 1845. She was a member of the Associated Artists in Water-Colours from 1807 to 1810, and letters by her relating to this society are in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Her large miniature of Queen Adelaide, signed ‘My Green’, is in the Royal Collection. Foskett noted that ‘she was a good artist who painted with freedom and placed her sitters well’ (Foskett, 550).

Green gradually attained a good reputation for his portraits in watercolour. In 1804 he had belonged for four years to an informal sketching club that included the patron and landscape painter Sir George Beaumont, Samuel Shelley the miniature painter, ‘Nattes and Hills drawing Masters and Pyne, a designer, who met weekly in each others' houses during the winter months to sketch and converse on art’ (Farington, Diary, 6.2271). His execution was more elegant than powerful, but his portraits do not lack dignity. Many of them have been engraved, including those of Benjamin West, president of the Royal Academy (original painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and Sir R. Birnie, both engraved in mezzotint by W. Say; George Cook, the actor, as Iago (Garrick Club, London), engraved in mezzotint by James Ward; and Joseph Charles Horsley (‘the stolen child’), engraved by R. Cooper. In the National Portrait Gallery, London, there are portraits by him of Thomas Stothard RA, William Say, Peter Nicholson, and Sir John Ross, the latter being Green's last work. The portrait of Stothard was sold at Samuel Rogers's sale in May 1856, as by George Henry Harlow, whose works Green's portraiture resembled at times although it is signed ‘James Green, 1830’. It was engraved by E. Scriven for the Library of the Fine Arts (April 1833). Green also painted large subject pictures in oil, including Zadig and Astarte (exh. RA, 1826, of which an engraving was reproduced in the Literary Souvenir, 1828); Bearnaise Woman and Canary, engraved, and reproduced in the Literary Souvenir (1827); and Belinda. His picture The Loves Conducted by the Graces to the Temple of Hymen was painted in watercolour. Green also was a frequent exhibitor from 1806 to 1832 at the British Institution, where he showed mainly genre and subject pictures, and in 1808 was awarded a premium of £60. He was a member of the Associated Artists in Water-Colours. Many of his pictures were commissions, notably from Francis Chaplin of Riseholme, Lincolnshire. He resided for many years at Rathbone Place, London, and subsequently at 8 South Crescent, Bedford Square, London. He died at Bath on 27 March 1834. He was buried in Walcot church. On her husband's death Mary Green retired from her profession, though she continued to exhibit; she died on 22 October 1845, and was buried at Kensal Green, Middlesex. Her copies after Reynolds and Gainsborough were much valued. James and Mary Green had two children,Benjamin Richard Green and a daughter.

L. H. Cust, rev. John Sunderland DNB