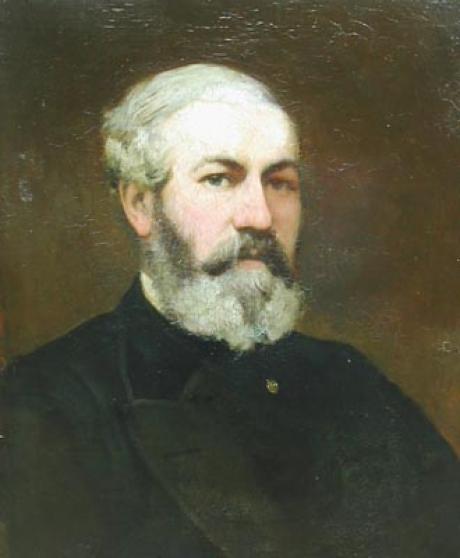

Sir Thomas Bouch, (1822–1880), civil engineer, was born on 22 February 1822 at Thursby, Cumberland, the third son of William Bouch, a captain in the mercantile marine and his wife, Elizabeth Sanderson. At the age of seventeen he was employed for four years on the construction of the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway, for which the engineers were Locke and Errington. He subsequently served four years as resident engineer on the Wear Valley Railway during its construction, and worked on other railways in the north of England.

In 1849 Bouch became engineer and manager of the Edinburgh and Northern Railway (later known as the Edinburgh, Perth, and Dundee Railway). In this capacity he became interested in the problems of railway crossings of the Forth and Tay estuaries, and developed a train ferry or ‘floating railway’ (partly financed by Sir John Gladstone) for taking goods wagons over the Forth between Granton and Burntisland. The wagons ran on rails directly onto rails on the ferry and were taken off in the same way. This system worked well over a number of years. In 1853 Bouch married Margaret Ada Nelson; they had a son and two daughters.

Shortly after completing the work on the Forth, Bouch left the Edinburgh railway company and set up as a consulting engineer, mainly on the development of railways in the north of England and in Scotland, and for tramways in London, Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Dundee. In total he was the engineer for the construction of about 270 miles of railways, chief of which was the South Durham and Lancashire Union, 50 miles long. His largest railway in Scotland was the Edinburgh to Peebles line, 21 miles in length and for a long time the pattern for cheap construction. His railways demanded many bridges, including the Beelah Viaduct, with sixteen spans of 60 ft each and 196 ft high, and Deepdale, which had eleven spans of 60 ft with a maximum height of 160 ft. These bridges were very economically designed, comprising lattice girders on iron piers composed of groups of braced columns, and carried railway traffic for over a hundred years before being dismantled. Bouch also constructed a remarkable road bridge in 1871 at Newcastle, the Redheugh Viaduct, which consisted of two spans of 260 ft and two of 240 ft. These spans were of lattice girders supported by raking ties and bore a striking resemblance to the cable-stayed bridges of today.

Bouch was thus well equipped to realize the dream of his life, which was to bridge the Forth and the Tay estuaries. His opportunity to bridge the Tay came first, an act being passed in 1870 for the purpose. The scheme proposed by Bouch crossed the river between Wormit and Dundee and was a few yards short of 2 miles long, by far the longest bridge in the world at the time. It consisted of eighty-five spans, of which thirteen, at the deepest part of the channel, formed the navigation spans, longer and higher than the others. They were of lattice girders carried on piers formed of groups of cast-iron columns. The original design had the lattice girders carried on tall brick piers, but owing to misleading information on ground conditions the brick piers had to be replaced by lighter iron construction over most of the bridge length after construction had begun. This change had a significant effect on the strength and stability of the bridge.

The bridge was passed by the Board of Trade and opened in May 1878. Queen Victoria journeyed over during the following year and knighted Bouch on 26 June 1879. He was meantime engaged on his design for a bridge at Queensferry to cross the Forth. Construction of this bridge with two main spans of 1600 ft was begun in 1878, again a gigantic leap forward in bridge design, as the longest railway spans hitherto constructed in Britain were of 460 ft, over the Menai Strait.

However, on 28 December 1879 a violent storm caused the collapse of the navigation spans of the Tay Bridge while a train was crossing, and seventy-five lives were lost. The subsequent inquiry found the cause of the collapse to be inadequate bracing of the ironwork of the tall piers. It seems likely that defects in the casting of the columns also contributed to the collapse. The inquiry did not apportion blame for the disaster, but one of the panel members (a Mr Rothery), in a separate report, placed the blame on Bouch. Work on his Forth Bridge was stopped, and he was relieved of his post as engineer. These events affected Bouch's health, and he died from heart disease the following year, on 30 October 1880, after premature retirement to Moffat. He was buried in Dean cemetery, Edinburgh. He was survived by his wife. It may be said of him that he perhaps designed his bridges with a lower margin of safety than other engineers, but displayed boldness and originality in many of them, and had a distinguished career until the collapse of the Tay Bridge. It could also be said that he pointed the way to the eventual successful bridging of the Forth and Tay at locations which were first chosen by him.

J. S. Shipway

English

School 19th

Century

Portrait of Sir Thomas Bouch 1822 - 1880

Portrait of Sir Thomas Bouch

oil on canvas

61 x 51 cm. (24.02 x 20.08 in.)

£1800

Notes