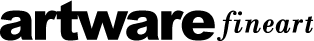

signed lower right, and further inscribed on a label verso ‘Dorothy Payne, Manor House, Reigate. Sir Vivian Fuchs’

Wearing a Cossack's Tunic and smoking a Pipe

Sir Vivian Ernest Fuchs FRS 11 February 1908 – 11 November 1999 was an English scientist-explorer and expedition organizer. He led the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition which reached the South Pole overland in 1958. Standing at more than 6ft, strong, austere and possessing thunderous eyebrows, Vivian Fuchs was a natural leader who had no need to coerce people to get his way. An explorer with instinctively big ideas, he was also a patient and painstaking master of detail, which ensured that the first surface crossing of the Antarctic, in 1957-58, was successfully concluded, despite something of a contretemps between Fuchs and Sir Edmund Hillary along the way.

Vivian Ernest Fuchs, known as "Bunny", was the son of Ernest Fuchs, who had emigrated from Germany as a child, become a successful farmer and married an Englishwoman, Violet Watson. Sir Vivian Fuchs was born on 11 February 1908 at Freshwater on the Isle of Wight. His father, Ernst, was German and his mother, Violet, was English. After a brief period living in Wandsworth, the family moved to Staplehurst in Kent, where Ernst had acquired land on which he built a house called Walden. Here the family lived happily, until war was declared on 4th August 1914 and their peaceful lives were shattered.

Walden was in a 'prohibited area' and had to be closed. All German residents in the UK were ordered to be imprisoned, and so Ernst was taken away to a camp at Newbury, along with 1,000 other men. A gathering emotional storm swept the country, and anti-German feeling was rife. After some time Violet learned that if she could provide a financially-supported guarantee of where the family would live, Ernst might be released. The family were reunited and moved to Douglas on the Isle of Man.

In May 1915 Ernst was again imprisoned, this time in a camp on the Isle of Man. In the spring of 1917 civilian labour on farms was in such short supply that selected prisoners from the camps were permitted release to work on the land. Ernst was among them, and went to work in Kent, although the family were not permitted to join him. Shortly after this Violet's parents died, but left no will. Violet's inheritance was sequestered by the government, on the grounds that she was considered an 'enemy alien', and so for six long years after the war ended and the family had been permitted to return to Walden, they lived a hand-to-mouth existence. Renouncing his German nationality, Ernst eventually succeeded in his application for naturalization as a British citizen in 1927.

In 1917 Vivian went to Asheton Preparatory School near Tenterden in Kent, where he became Head Boy and acquired the nickname 'Bunny', which stayed with him for life. He developed interests in sports and natural history, and in the summer holidays enjoyed walking and rowing in Scotland.

Violet began the long struggle to regain the family's seized capital, eventually succeeding in 1924. But the shadow of the war was long, and on his application to Tonbridge, the family were told that Vivian might only be admitted only after every English boy had been accepted. After a brief and unhappy period at Trent College, Vivian went to Brighton College, where he decided to pursue subjects that would 'keep him outdoors', particularly geology and zoology.

Fuchs was educated at Brighton College and St John's College, Cambridge, where he read natural sciences. His interest in polar exploration was aroused by his tutor, Sir James Wordie, who had been with Shackleton on the abortive Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-16, when their ship, the Endurance, was wrecked in the Weddell Sea. Fuchs was the geologist in a team which Wordie took to East Greenland in 1929. Wordie became Fuchs's influential mentor and took him to the Arctic on an expedition. Much later, Wordie was key in supporting the planning of the Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

Fuchs read Geology, Zoology and Botany, graduating in 1930 with a Third. Always keen on sport, he played in the College Rugby XV, rowed, played tennis and cricket. His parents gave him a small two-seater silver Austin 7, named Lepsima after the arthropod (commonly known as a silver fish) which led to an enduring passion for fast cars. Lepsima was later followed by a Riley sportscar, two MGs, a Sunbeam Talbort and a succession of Jaguars.

'Roof climbing' was popular among some of the students, including Fuchs. Staying out at night was not permitted and students were required to be in College by 10pm, but it was said that there were at least 14 ways of getting back inside the College without using the front gate. This activity did not go unnoticed - much later, Wordie sent an account to the Times of a summer expedition to Greenland, in which he mentioned that 'the ninth member of the team gained his [mountaineering] experience among the roofs and towers of Cambridge'.

After exams in the summer of 1929, Fuchs was invited to join James Wordie on his summer expedition to Greenland. On 2nd July the party of four geologists, two surveyors, a doctor and a physicist, sailed from Aberdeen aboard the Heimland, a 64-ton Norweigan seal-hunting ship. Six days later the ship entered the pack ice and progress became slow. Stuck fast in the ice, time passed with short expeditions catching seal and bear to eat, collecting and identifying animals, plants and birds. After a month of slow progress through the ice, they at last sighted Greenland and sailed up the Franz Josef Fjord to anchor inland at Kjerulf Fjord, long behind schedule with only three weeks left to complete the field work, which included climbing Petermann Peak. Wordie and two others reached the summit (9650 ft) on 16 August in dangerous conditions.

The Greenland expedition was Fuchs's first experience of polar work, and was to shape his future as explorer, scientist and leader. He describes this expedition as a 'memorable baptism of ice'. Following the Greenland Expedition Fuchs returned to Cambridge for a fourth year to read Geology and, encouraged by Wordie, to write a paper with a fellow expedition member on some of their findings - his first publication.

Fuchs was the son of the German immigrant Ernst Fuchs from the Jena area and of his British wife Violet Watson. He was born in 1908 in Freshwater, Isle of Wight, and attended Brighton College and St John's College, Cambridge. He was educated as a geologist, and considered the profession a means of pursuing his interest in the outdoors. He was a member of the Sedgwick Club, a geological society, at Cambridge. His first expedition was to Greenland in 1929 with his tutor James Wordie.

After graduation in 1930, he travelled with a Cambridge University expedition to study the geology of East African lakes with respect to climate fluctuation. Next, he joined anthropologist Louis Leakey on an expedition to Olduvai Gorge. In 1933 he led his own expedition to Lake Rudolf, and in 1935 he submitted his doctoral thesis on the tectonic geology of the Rift Valley. The Royal Geographical Society's Cuthbert Peek Grant in 1936 encouraged him to investigate geology further south, around Lake Rukwa.

In 1933, Fuchs married his cousin, Joyce Connell. A world traveller in her own right, Joyce accompanied Vivian on his expedition to Lake Rudolf (now Lake Turkana) in 1934. The findings from this expedition, in which two of their companions were lost, brought Fuchs his PhD from Cambridge in 1937.

Through an acquaintance with Louis S B Leakey, research fellow at St John's College, Vivian Fuchs was introduced to Dr Barton Worthington and on the recommendation of his tutor, James Wordie, was recruited as geologist to the 1930 - 31 Cambridge Expedition to the East African Lakes. The objective was to study the biology and geology of the lakes in the Great African Rift Valley.

Often working alone, Fuchs quickly grew acclimatised to the harsh conditions and was just as captivated by the vast, hot continent as he had been by the Arctic pack ice. After Lake Baringo in Kenya, the expedition moved on to Lake Rudolf (now Lake Turkana) in northern Kenya, using vehicles and camels to transport men and equipment. On return to Baringo Fuchs became seriously ill with malaira, and was hospitalised in Nairobi for two months before he rejoined the expedition. In western Uganda, he travelled into what is now Zaïre and spent a month studying Lake George.

In 1931 Fuchs joined Louis Leakey on an archaeological expedition to Olduvai in Tanzania, finding stone-age tools and mammal fossils which were sent to the Natural History collection at the British Museum.

In 1933 Fuchs married his cousin, Joyce Connell. A world traveller in her own right, Joyce accompanied Vivian on his expedition to Lake Rudolf (now Lake Turkana) in 1934. Plans were submitted to the Royal Society, Royal Geographical Society and other funding bodies, to raise the £2000 necessary to sustain six men for a year on the expedition.

In Kenya, west of Lake Turkana, they collected the first pre-Neolithic implements found in the lake basin, then travelled north to the frontier with Sudan. Returning to Naivasha, the expedition re-fitted for the second part and set out for Lake Turkana to resume geological and survey work. Here they made the first recorded visit to South Island and found signs of human occupation. When Fuchs returned to the mainland to continue his geological work, disaster struck and his two companions were lost. After intensive searches for more than eight days the search had to be called off.

Although Fuchs's first expedition had ended earlier than planned in tragic circumstances, the scientific work was not lost and led to his PhD.

In 1935 Joyce and Vivian Fuchs bought their first home, at 72 Barton Road in Cambridge. In February 1936, their daughter Hilary was born. The following year they bought the house known as Barton Cottage, 79 Barton Road and the next door plot 76 Barton Road (undeveloped). Barton Cottage was later sold and the house and garden eventually acquired by Wolfson College.

After writing up his PhD at the Sedgwick Museum (now Department of Earth Sciences) at the University of Cambridge, Fuchs organised an expedition to investigate the Lake Rukwa basin in southern Tanzania in 1937. Sadly, when he returned in 1938 to a new daughter, Rosalind, she was diagnosed with severe cerebral palsy, with tragic consequences for the family. Rosalind died aged almost eight in 1945. His son, Peter, was born in 1940.

Fuchs served in West Africa during 1942-43 but was recalled to attend the Staff College at Camberley, and was then posted to North Western Europe, where he was mentioned in dispatches. While Fuchs was writing up his research from the Lake Rukwa expedition and negotiating for a job with one of the East African Geological Surveys, he joined the Territorial Army. When war was declared on Germany in 1939, he became Adjutant to the Second Battalion of the Cambridgeshire Regiment, later joining Brigade HQ as Transport Officer. He was given compassionate leave in 1940 for the birth of his son, Peter.

Given his experience and fluent Swahili, Fuchs volunteered for service in East Africa, but was posted to West Africa, where Swahili was of no use. In the Gold Coast the troops felt left out of the war. In June 1943 Fuchs was chosen for one of the highly coveted places alloted to the West African Command on the Camberley Staff course in the UK, and in September arrived home for a month's leave, able to get to know his children again.

At the end of a condensed course of four months (reduced from a year), Fuchs qualified and was posted to Second Army HQ in London to work in Civil Affairs. This also gave him the opportunity to visit his father regularly, and they kept in close contact during the following months. Six weeks before D-Day his unit left London for Portsmouth to prepare for the invasion of France. Four days after D-Day, Fuchs's group crossed the English Channel to 'Gold Beach' on the French coast. Civil Affairs moved in behind the tanks to set up administration, slowly moving through France then advancing rapidly through Belgium and into Holland, where Fuchs stayed for several months. On crossing the border into Germany Fuchs witnessed the first prisoners liberated from Belsen concentration camp - hardly able to walk with their tattered clothes hanging from their emaciated bodies.

The unit travelled through the chaos of devastated Germany to Schleswig-Holstein, where Fuchs became responsible for a Kreis (equivalent to an English county) with his HQ in Plön. The bureaucracy was inevitably stifling and counterproductive, but Fuchs made the system work, learning the language and legal procedures, holding court, managing the dispersal of German refugees returning from the Russian front. During this time he made many friends and learned skills that were to prove useful in later life.

Having volunteered to remain in Plön after the end of the war, by October 1946 Fuchs felt ready to leave Germany, and returned home to his family. He was demobilised as a major in 1946. At the age of thirty, he enrolled in the Territorial Army, and was dispatched to the Gold Coast from 1942 to July 1943. He returned home and was posted to London at Second Army headquarters in a civil affairs position. The Second Army was transferred to Portsmouth for the D-Day landings, and Fuchs eventually reached Germany in time to see the release of prisoners from the Belsen concentration camp. He governed the Plön district in Schleswig-Holstein until October 1946, when he was discharged from military service with the rank of Major.

Fuchs was involved with the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (now the British Antarctic Survey) beginning in 1947, when he applied for a geologist position. The institute's goal was to promote Britain's claims to Antarctica, and secondarily to support scientific research. In 1947 Fuchs learned of the Falklands Islands Dependencies Survey - whose members were known as Fids - which then occupied seven bases in the Antarctic. The primary purpose was to strengthen Britain's claim to sovereignty. Fuchs applied for a position as Geologist, was interviewed and offered the job of overall Field Commander of all the Antarctic activities, based at Stonington Island on the Antarctic Peninsula.

Fuchs was one of 27 Fids to travel to the Antarctic in December 1947, and was given the freedom to plan the scientific programme for the duration of their stay. At Stonington, eleven men lived in cramped quarters and Fuchs quickly became the natural, as well as the appointed, leader of the group. Between 1948 and 1950 the men made a series of expeditions south from their base on the Peninsula.

The group had planned to have the use of an aircraft for their expeditions but some vital parts had been left behind and so all travel was by dog-sledging. Like the other new men Fuchs had to learn to drive a team; his lead dog was 'Darkie' with whom he developed a close rapport.

From October 1948 the Governor of the Falkland Islands, Sir Miles Clifford, took charge of the FIDS. In April 1949 the sea ice remained fast in Marguerite Bay and the relief ship John Biscoe could not reach Stonington, so the men were stuck for a further winter - for five of them this was their third consecutive winter. They became known as the 'Lost Eleven' and lasting bonds were formed. Despite the failure of the relief ship to deliver new supplies, Fuchs and his colleagues had a productive year, including a study of emperor penguins at a newly discovered colony.

In 1950 the sea ice cleared in early February and the ship was finally able to get through. Stonington Base was closed and all except 36 dogs had to be put down, because no more than this could be accommodated on board ship. The surviving dogs were dispersed to other bases - a team of nine returned to Britain and performed in the Festival of Britain, led by Darkie, who later went to live with Fuchs and became a familiar sight in Cambridge. Fuchs returned to the UK by sea via the Falkland Islands, the port of Santos in Brazil, Lisbon (Portugal) and finally to Southampton. The following year he was appointed leader of the Falklands Islands Dependencies Survey (which became the British Antarctic Survey in 1961). It was a job after his own heart - a strenuous, open-air life with a scientific purpose, in the company of a small party of fellow workers as keen and efficient as himself. The team had no mechanised transport and were entirely dependent on dogs. Exceptionally severe ice conditions in 1949-50 kept them in the Antarctic without relief for two seasons. The idea of reviving Shackleton's grand design of a trans-Antarctic crossing first presented itself to Fuchs's mind during the bitter season of 1949-50, when blizzards hampered activity and there was sometimes little to do but to take shelter and plan ahead. With the mechanical transport and air support now available, a scientific programme could be undertaken on such a crossing, and Fuchs was particularly interested in the possibility of carrying seismic equipment to determine the thickness of the Antarctic ice.

London Office, Crown Agents, was responsible for supplies, equipment and recruitment for the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey. Returning to Britain from the Antarctic in 1950, Vivian Fuchs was appointed Principal Scientific Officer for the FIDS and set up another office in London, the FIDS Scientific Bureau.

Fuchs's brief was to interview scientists returning from the Antarctic, organise where and how they should write up their research, and make arrangements for publishing the research and distributing specimens collected. Inevitably these duties grew rapidly and before long the new office was well established and fulfilling many more duties than the Survey had anticipated.

Fuchs worked in conjunction with the independent logistics operation based in the Falkland Islands and with a UK Scientific Committee, working to political and scientific objectives with a split command that made life difficult. However, Fuchs persevered and in 1953 the life of the Bureau was extended for a further three years and it became an integral part of the FIDS.

The second half of the 1950s and into the 1960s was a peak period in British Antarctic affairs. The International Geophysical Year (IGY) in 1957 - 58 brought an unprecedented number of scientists to the Antarctic, and in 1956 the Royal Society established a scientific station at Halley Bay. In 1955 - 56 the Falkland Islands Dependencies Aerial Survey Expedition (FIDASE) was launched, and in 1958 the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (TAE) under Fuchs's leadership accomplished the first land crossing of the Antarctic.

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition was divided into two parts. Sir Edmund Hillary was to lead a New Zealand team to establish Scott Base on the Ross Sea, in their own sector of the Antarctic, where the journey was to end. Fuchs was to lead the main party from Shackleton Base on the Weddell Sea to the United States station at the South Pole, and from there to the coast through an area already surveyed by Hillary, and provided with supply dumps. Having scooped the world with news of the conquest of Everest, The Times secured copyright on all press features from the expedition.

Fuchs's qualities of leadership were apparent from the beginning: in his equanimity during the Theron's daunting passage of the ice-bound Weddell Sea in 1956, and in the speed and resolution with which he put ashore his advance party late in the season and in worsening weather. Swift action was vital if enough stores and equipment were to be landed to enable Ken Blaiklock and his team to build the foundations of a base for the expedition's main task in the following year. They had to be landed before the winter ice, already closing in, blocked the Theron's passage home. The survival of the advance party and the accomplishment of their programme, despite the loss of stores in a gale, says much for the skill with which Fuchs had picked his men.

The main party were back in Antarctica in February 1957. An intermediary station was erected at South Ice, 275 miles inland, and on November 24 the crossing was begun in six tracked vehicles with dogs and aircraft in support. Throughout what was to prove one of the "worst journeys in the world", Fuchs maintained absolute discipline and high morale, showing neither depression at delay nor elation at progress. The order in which the cavalcade moved forward never varied: Fuchs was always the leader either in his Sno-Cat, Rock'n'Roll, or in the heavily crevassed areas, probing the way in one of the lighter Weasels.

Meanwhile, the New Zealanders made such good time that Hillary took the controversial decision to press on with his Ferguson tractors beyond the last supply depot to the Pole itself. They reached Amundsen-Scott Base in a spectacular dash on January 4, 1958, while "Bunny's Boys" (as the Americans called them) were still nearly 400 miles away, labouring to make up time lost in the appalling terrain between Shackleton and South Ice.

It remains debatable how far Hillary was entitled to set aside Fuchs's request for him to dig in short of the Pole to await the main crossing party so as to act as their guide for the rest of the way. Later, in the benign atmosphere of a Royal Geographical Society dinner, Fuchs maintained that "the great Antarctic row never existed at all". There was, however, at least a clash of personalities - which was brought into the open by the leaking to the press of radio messages exchanged between the two men.

Hillary had offered some rather high-handed advice to Fuchs to call a halt at the Pole, have the Americans fly him out, and so allow the New Zealanders to return home before winter set in. Perhaps the journey could be resumed in the following season. Fuchs roundly rejected such an idea and declared his intention of carrying on as planned, if necessary without New Zealand help. His men, he said, would "find their own way out". Hillary at once agreed to abide by the original arrangement and the second, longer leg of the journey proved easier than the first. Later, Fuchs paid handsome tribute to Hillary's co-operation. Leaving the Pole on January 24, Fuchs's party completed the first land crossing of the White Continent in 99 days, one fewer than their leader's original estimate. Along the way a substantial scientific programme had been accomplished, including seismic soundings and a gravity traverse. During episodes of bad weather on long journeys from Stonington Island in 1948 and 1949, Fuchs had begun to develop plans for an expedition to cross the Antarctic from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Sea. This had previously been attempted, unsuccessfully, by Wilhelm Filchner in 1911 and by Ernest Shackleton in 1914.

In April 1955 Fuchs took leave from the Bureau to plan and undertake the Trans-Antarctic Expedition. There was much to do. Financial support had to be secured - some £725,000 (about £10 million today). He received support from his old friend and tutor at Cambridge, James Wordie, but was opposed by many in the British polar / geographical establishment, some seeking funds for the FIDASE.

However, Sir Winston Churchill supported his plans and eventually the Treasury, the governments of New Zealand, Australia and South Africa, were won over and gave their support. After the UK, New Zealand contributed the most, so was given the decision to select the leader of the Ross Sea Party and Scott Base, and chose Sir Edmund Hillary.

There were three components to the expedition: the Advance Party, who landed on the Filchner Ice Shelf at the head of the Weddell Sea; the Ross Sea Support Team, who laid depots from McMurdo Sound in the Ross Sea to the South Pole; and the Expedition party, led by Fuchs. Field teams included men from Britain, New Zealand, Australia and South Africa.

The expedition ship Theron carrying Fuchs and the Advance Party, was delayed by pack ice and so the unloading of stores could not begin until the end of January 1956 - very late to be so far into the ice on a small ship. In 1955 - 56 a base site at McMurdo Sound was established for the New Zealand team, and Scott Base was built. The main party arrived at Shackleton Base in January 1957 and at the beginning of October vehicles left to pioner the unknown route to South Ice, taking 59 days negotiating huge crevasses in appalling conditions.

On 24th November 1957 Fuchs and a team of 19 men with Sno-Cats and dog teams left Shackleton Base to begin the crossing of the Antarctic. Over challenging terrain the team encountered crevasses and they conducted scientific programmes, often travelling no more than 2 to 3 miles per hour, but averaging 22 miles per day, arriving at the South Pole on 19th January 1958. Meanwhile the Ross Sea party, led by Sir Edmund Hillary, departed Scott Base over easier terrian, reaching the South Pole ahead of Fuchs on 5th January. It was late in the season and conditions were difficult - Hillary urged Fuchs to break his journey at the Pole and finish it the following season, but Fuchs and his men continued with determination to complete the crossing as planned. On 2nd March 1958, Fuchs's team arrived at Scott Base in McMurdo Sound - a total journey of 99 days over 2158 miles. On 17th March 1958 the ship Endeavour carrying the Expedition party arrived in brilliant sunshine in the port at Wellington, New Zealand, greeted by the Magga Dan carrying the Expedition's families. A flight of New Zealand's Royal Air Force planes roared in the skies above as the people of Wellington gave the Expedition a hero's welcome. In his autobiography, Fuchs writes that "[after crossing Antarctica] at speeds of two to three miles an hour ... suddenly being driven with Ed Hillary through ... Wellington at thirty miles an hour was one of the most frightening experiences of my life!"

The Expedition docked at Southampton in May and travelled by train to London Waterloo, where they were officially welcomed by Sir Alec Douglas Home, Commonwealth Secretary. The streets were crowded as the Expedition party proceeded to the Royal Geographical Society for a press conference, in a procession of vehicles led by an open Phantom II Rolls Royce.

Two days later a private reception was held at Buckingham Palace in which Fuchs received his knighthood and every member of the expedition was presented with the Polar Medal. There followed a series of formal receptions, including an invitation to a reception hosted by the Prime Minister at Lancaster House in London, which ended with a very lively impromptu dance.

A lecture at the Royal Geographical Survey, with David Stratton, was the first of what became a tour of special appearances by various of the celebrated Expedition party, and it was here that Fuchs received the Society's Special Gold Medal.

In the months following there was endless demand for lectures and guest appearances that took Sir Vivian and his wife, Joyce, to Oslo, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Paris (where they were received privately by General de Gaulle). In February 1959 the Fuchs visited Washington DC, New York, Indianapolis, Chicago, Toronto and Montreal, a highlight of which was a visit to the White House to receive the National Geographical Society's Hubbard Medal from President Eisenhower.

During this time Fuchs was also able to catch up on family life. Hilary was by now married, after training as a nurse, and expecting a son. In 1959 Peter was offered a place at St John's College, Unievrsity of Cambridge, where he took a degree in Natural Sciences, majoring in Geology, and had his first experience of expeditions working in Alaska for BP.

Almost as soon as he returned from the Antarctic, Fuchs was under pressure to publish an account of the expedition, under contract with Cassell's. This he began within weeks of arriving home, and with four chapters coming from Edmund Hillary in New Zealand, the book was finished in eight weeks. Later translated into fourteen languages, sales of The Crossing of Antarctica were sufficient to close the gap in the Expedition's finances, and with the sale of one of the aircraft, the Expedition found itself in profit.

So it was that when the TAE office closed down, the Expedition formed the Trans-Antarctic Association with the remaining funds, and this Trust now makes awards on an annual basis to support individuals or organisations working in the Antarctic. When Fuchs returned home in 1950 he had proved himself an outstanding polar leader, and he was at once appointed director of the survey's scientific bureau. He also received the Royal Geographical Society's Founder's Gold Medal. On his return, Fuchs was knighted, qualified for a clasp to his Polar Medal of 1953, and became one of the very few explorers to whom the Royal Geographical Society has awarded a Special Gold Medal. Many other awards and honours followed.

In 1950 Fuchs was asked to develop the new London scientific bureau of the Survey, to plan research in the Antarctic and support research publication. After the trans-Antarctic expedition he become director of the Survey, a position he held until 1973. Fuchs returned to the Falkland Islands Dependencies Scientific Bureau in London at the end of 1958. In 1962, with the introduction of the Antarctic Treaty, the FIDS was renamed the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). As its first Director, Fuchs built up an effective team of admisitrators and set about turning the Survey into a Public Office.

The Treasury proposed the closure of the BAS, so Fuchs sought support from various Ministries, from the Royal Society, and from his now extensive network of influential contacts. The proposal to sustain the BAS was put forward for consideration by the Cabinet Office and the Survey's fate was referred to the Council for Scientific Policy, which advised that the BAS should continue given the scientific output already proven. The Council also supported the need for a new ship for the Survey. Fortunately the Cabinet agreed and the BAS was formally transferred to the National Environment Research Council in April 1967, with an annual budget of £1 million (today about £12 million). At last a sustainable structure and continuity in the scientific programmes was possible.

A variety of reserach groups that included Geophysics, Biology, Medicene and Zoology were established throughout the country, some with research stations in Antarctica. The BAS cooperated with the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge and in 1971 a BAS Glaciological Section was established there.

By 1971 the total number of men in the Antarctic was 92, including 45 scientists, surveyors and meterologists. By 1973 permanent staff in the UK numbered 53, increased each summer by an influx of contract staff being trained for Antarctic service, others writing up their research, and the additonal administrative staff required. In the UK it had long been planned to amalgamate the Head Office and various research groups scattered around the country, and so the transfer of the BAS to Cambridge was approved. In 1972 NERC agreed a site and sufficient funding, planning permission was granted a year later, and the BAS complex was operational by 1976.

During Fuchs's 14 years as Director, the British Antarctic Survey had undergone a transformation. By the time he retired in 1973, the total number of staff was around 350 and the annual budget around £1.5 million (equivalent to about £8 million today).With skill and vision Fuchs had guided the BAS from its political origins and emphasis on geographical exploration, to become a world leader in Antarctic research.

From 1958 to 1973, he was Director of the British Antarctic Survey, and from his home in Cambridge he exerted a continuing influence on polar affairs. He was President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1971, and in 1974 was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. He was President of the Royal Geographical Society from 1982 to 1984. He published his autobiography in 1985. Following Sir Vivian Fuchs' retirement from the British Antarctic Survey in 1973, two awards were established in recognition of his contribution to the Survey. One was the Fuchs Medal, to acknowledge outstanding service to the BAS. The other was the Fuchs Foundation, a charity to support educational and adventurous outdoor activities for young people, particularly from deprived backgrounds.

An active member of the Royal Geographical Society since 1958, Fuchs was President between 1982 and 84 and helped to develop the Expedition Advisory Centre in its role providing advice and training to scientific expeditions from schools and universities.

Fuchs made return visits to the Antarctic on several occasions and in 1977 he organised (with RM Laws) a Royal Society Discussion Meeting on Scientific research in Antarctica. In 1983 he flew to Kenya to visit the Royal Geographical Survey's expedition to the Kora River.

In 1982 Fuchs wrote Of ice and men: the story of the British Antarctic Survey and in 1990, published his autobiography, A time to Speak. Always a keen sportsman and happiest out of doors, Fuchs played squash well into his seventies and was a keen gardener. In 1985 he suffered a severe heart attack and for the first time had to adjust to a gentler pace of life. His wife, Joyce, was an enthusiastic supporter of his work and always hospitable towards FIDS and others in the geographical and polar worlds. In 1988 she collapsed with a heart attack while out walking, and two years later died in his arms, crossing a road in Oxford, the day before the marriage of their eldest grandson. They had been married for 57 years.

Fuchs married again, to Eleanor Honnywill in 1991. She had worked with him for nearly 50 years, ran the London Office of the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey during Fuchs's Trans-Antarctic Expedition, and was appointed his personal assistant as Director at the British Antarctic Survey.

In July 1996 Fuchs went into hospital for a serious abdominal operation, which led to a stroke four months later and left him partially paralysed - which he fought with characteristic determination. Sir Vivian Fuchs died on 11 November 1999, at the age of 91.

From 1982 through 1984, Fuchs was president of the Royal Geographical Society. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1974. In 1933, he had married his cousin Joyce Connell, who had accompanied him on several expeditions. They had three children: Hilary (1936-2002) Rosalind (1938–1945), and Peter (born 1940). Joyce, Lady Fuchs, died on 27 April 1990 in Oxford, of a heart attack, aged 83. The next year, in 1991, he married Eleanor Honnywill, his former personal assistant at the British Antarctic Survey, in Kensington and Chelsea, London Sir Vivian Fuchs died in Cambridge on 11 November 1999, aged 91.

Legacy

- The Fuchs Medal was created in 1973 for "outstanding devotion to the British Antarctic Survey's interests, beyond the call of normal duty, by men or women who are or were members of the Survey, or closely connected with its work." It is awarded to one or two people per year.

- Fuchs Dome in the Shackleton Range, Antarctica.

- Fuchs Ice Piedmont on Adelaide Island, Antarctica.