signed inscribed and dated

Stanley Ghyll is now open again after a major project to bring back its natural wildlife and its view.

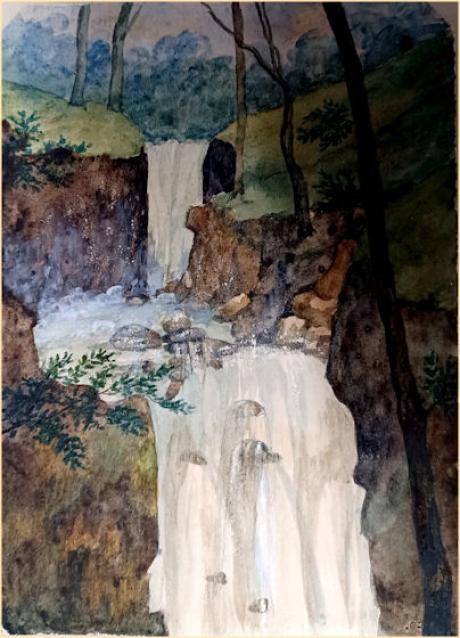

Stanley Ghyll is “one of the finest waterfall ravines in the Lake District”. The humid, sheltered conditions within the Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) protect a rich community of mosses, lichen, liverwort and notable rare ferns. The Beck, the waterfall and adjacent woodlands form the most important habitat for these plants in southwest Lakeland. Moreover, the awe-inspiring landscape and unusual biodiversity motivated exploration en-masse and Stanley Ghyll became a popular destination for tourism and artistic endeavour in the late Georgian and early Victorian eras.

The site was purchased by the Lake District Special Planning Board (which later became the Lake District National Park Authority) from the Ponsonby and Dalegarth Estate in 1994, with the object of preserving nature conservation interests and providing access opportunities for the public. From various historical documents and drawings we know that prior to the 1850s, rhododendron did not exist on the property. Bare granite and native species dominated the landscape and the waterfalls could be viewed and heard from a great distance.

About this time, the property served as a nursery for the gardens of Muncaster Castle and the Victorian fascination with rhododendron saw the planting of many different species throughout the site in the spring of 1857. The common, invasive ponticum variety thrived in the steep sided ravine of Stanley Ghyll and in less than one hundred years, the property was a sprawling mass of densely packed, unchecked rhododendron growth; poisoning the soils, shutting out the light and the views and preventing the natural progression of the native species.

Tumbling over the wooded ridgeline between this cultivation and the hinterland is Stanley Ghyll Force. It’s believed the waterfall had been called Dalegarth Falls and was renamed by a member of the Stanley family who lived at Dalegarth Hall. There’s a car park beside the hall, a half-mile walk from the falls.Another route leaves Boot along bridleways via St Catherine’s Church. With no tower, the church sits squat on the farmland, simple and humble. It’s said a sixth-century hermit lived at a holy well on this site, offering a blessing to anyone dedicated enough to find him.

From here, use the stepping stones to cross the Esk. If the river is in full flow, there’s a footbridge a short distance upstream. When it’s calm and safe, wild swimmers dive into the plunge pools at the base of Gill Force near the bridge. Here, the emerald waters of the Esk have cut ravines into the bedrock with their flow.Once across the river, you enter woodland where mosses cover boulders and encroach upon the bark of trees. Red squirrels inhabit the area. Closing in on the gorge on the fern-lined path, a gathering of fir trees gives way to more native trees and exotic-feeling rhododendrons. The way clings to the edge of the beck as the land rises either side and trees hang above. Several footbridges cross the granite streambed, polished smooth by the water’s flow.

Arriving at the base of the sublime Stanley Ghyll Force, it feels like you’ve entered an ageless sanctuary where time and water flow past in equal measure.